Comets The Mysterious Voyagers Junichi Watanabe

Comet ISON, once expected to become a “comet of the century,” failed to survive when it approached the sun in late November 2013. But the images of its demise – the comet extending its long, bright tail as it approached the Sun – were very impressive. Such images were captured with a super-sensitive 4K camera system by astronaut Koichi Wakata, who is on a long-term mission on the International Space Station. But ISON was just one of four comets that were seen in the Earth’s sky in November. Dr. Junichi Watanabe, the Deputy Director General of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, talks about the fascination we have with comets.

Could dusty snowballs help solve the mystery of the birth of the Solar System?

2013 was said to be a year of comets. Which comets were observed?

Comet Lovejoy (C/2013R1) (courtesy: Toshio Ushiyama)

Comet Lovejoy (C/2013R1) (courtesy: Toshio Ushiyama)

We had Comet PANSTARRS in March, and apart from ISON, Lovejoy (C/2013R1), 2P/Encke, and LINEAR(C/2012X1) in November. These comets got brighter when they happened to pass near the sun, all in a very short period. And in addition to these, there are many fainter ones that we never saw.

Comet Lovejoy (C/2013 R1), expected to reach its perihelion [the point in its orbit when it’s closest to the sun] on December 23, was discovered by an amateur astronomer in Australia named Terry Lovejoy, who also found another Comet Lovejoy, C/2011W3, in 2011. In Japan, you can see Comet Lovejoy with binoculars in the eastern sky at dawn during December, so I hope that you will enjoy the view. The most important tip for comet watching is to make sure you have the right time, place and direction. The light of a comet is faint, so you should choose a dark place, where you can see stars.

To go back to basics, what is a comet?

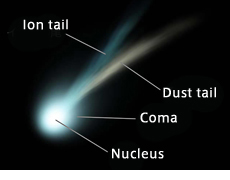

Structure of a comet (courtesy: NAOJ)

Structure of a comet (courtesy: NAOJ)

A comet is a massive icy object travelling from the edge of the solar system. The core of a comet is called the nucleus, composed of 80% water and 20% carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, etc., with sand-like particles mixed in. Simply put, comets are “dusty snowballs,” whose surface is covered with sand and dust. Their size ranges from a few hundred meters to tens of kilometers in diameter.

When a comet is heated by the sun, its icy surface melts, releasing dust and gas. Its tail is made up of that dust and gas, and may be classified as one of two kinds, depending on its ingredients and look. One is a dust tail – comprised of dust released from the comet’s nucleus. The dust reflects sunlight, which is how it gets its glow. The other is an ion tail, in which electrically charged gas particles emit a bluish light. A comet’s tail is believed to become brighter and longer as it approaches the sun. The more dust the comet contains, the more spectacular its tail becomes. Because the tail looks like a broom, a comet is also traditionally called a “broom star” in Japan.

Where do comets come from?

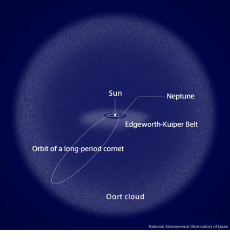

Scientists believe that comets are coming the Oort Cloud and the Kuiper Belt, regions full of icy planetesimals. The Oort Cloud is located at the edge of our solar system, and the Kuiper Belt is outside the orbit of Neptune. The icy planetesimals were created when the solar system was born 4.6 billion years ago, and comets are objects that changed their orbits for some reason and moved into the orbit of the solar system. So it is possible to try to explain the birth of the solar system by studying comets.

What are the orbits of comets like?

Orbit of a long-period comet (courtesy: NAOJ)

Orbit of a long-period comet (courtesy: NAOJ)

![]()

Based on the study of the orbits of the comets observed to date, there are two main types. One is short-period comets: they have a relatively small orbit, which means they orbit the Sun in a fairly short period. They typically orbit close to the plane of the ecliptic. Approximately 250 short-period comets have been discovered, including Comet 2P/Encke, which was seen this year. Some of these comets revolve around the Sun in the opposite direction. The most famous of these is probably Halley’s Comet, which has a 76-year period, so this type of comet is sometimes called Halley-type. The second type is comets with a very large, elongated orbit and a very long orbital period. These are called long-period comets. Some have a parabolic trajectory or a hyperbolic trajectory, and never come back once they emerge. We call this type long-period comets. Comet ISON is one of these – it has a parabolic trajectory. ISON got so much attention because it could be seen only once in a human lifespan.

What we learned from Comet ISON

Comet ISON seems to have dissipated at its perihelion, the closet point to the Sun. Why was ISON expected to become a Great Comet?

Comet ISON photographed by astronaut Koichi Wakata on the ISS (courtesy: JAXA/NHK)

Comet ISON photographed by astronaut Koichi Wakata on the ISS (courtesy: JAXA/NHK)

The reason was that ISON had a massive core, and yet it was coming extremely close to the Sun. ISON’s nucleus was estimated at about 4 kilometers across, similar to the size of Comet Ikeya-Seki, which became a Great Comet. And ISON’s perihelion was about 1.1 million kilometers from the sun – about three times greater than the distance between the Earth and the Moon. You may think this is very far away, but from a cosmic perspective it is so close that you can say Comet ISON grazed the Sun. Because ISON was visible from Japan, there was a lot of buzz about it.

How did Comet ISON display itself?

Comet ISON (courtesy: Toshio Ushiyama)

Comet ISON (courtesy: Toshio Ushiyama)

For some time, ISON was not brightening as much as expected, so we thought we might have to give up on it. But suddenly, in the middle of November, it started to shine. Its brightness was magnitude 9 at the beginning of the month, but by the 16th had increased to magnitude 5. So ISON was expected to become a Great Comet after passing its perihelion on the 29th…

What happened to ISON that day?

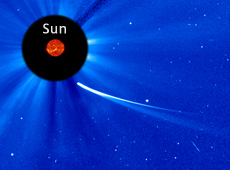

Comet ISON imaged by a solar observation satellite

Comet ISON imaged by a solar observation satellite

I was observing Comet ISON at Hida Observatory, at Kyoto University. But the comet was estimated to be passing its perihelion at dawn, so I was following its progress on the Internet, with images taken by solar observation satellites. Then, just before passing its perihelion, ISON started to dim. By the time it passed it, it had become like a very thin cirrus cloud. The nucleus seemed to have dissipated.

What is on your mind now after the experience with ISON?

I have realized how few comets have been scientifically observed, and how difficult it is to make predictions based on our limited samples.

Each comet is unpredictable and mysterious

What makes comets interesting to you?

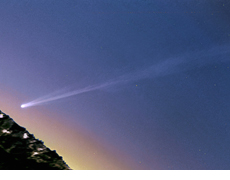

Comet McNaught (courtesy: ESA/NASA/SOHO)

Comet McNaught (courtesy: ESA/NASA/SOHO)

It’s the fact that no two comets are the same. I find it fascinating that each one is so unique. Will a comet melt and disappear as it approaches the Sun? Or will it transform, and become even more spectacular? No one can answer these questions. I like that comets are so unpredictable and mysterious.

For example, Comet McNaught, the Great Comet of 2007, began to get brighter two weeks before it reached its closest point to the Sun. Its rapid growth did not stop even at its perihelion, and McNaught was even visible in daylight. Unfortunately it could be seen only in the Southern Hemisphere, but at its brightest, it could even be seen right beside the Sun in the daytime in Japan. Nobody had expected Comet McNaught to become a Great Comet, and this is the very best thing about comets: it’s thrilling to imagine how they will turn out. Comets are the best! (laugh)

What’s the most impressive comet you’ve ever seen?

Comet Hyakutake (courtesy: Toshio Ushiyama)

Comet Hyakutake (courtesy: Toshio Ushiyama)

It would have to be Comet Kohoutek in 1973 and Comet West in 1976. I watched both in Japan. Kohoutek failed to meet expectations to become a Great Comet. West, on the other hand, was not expected to, but to everyone’s surprise became one. These two comets were such a contrast, I remember them very well.

I also clearly remember Comet Hyakutake, which appeared in March 1996. Its tail was recognized as the longest of the 20th century. With the head of the comet in the northern sky, the tail stretched over the zenith and into the southern sky. Actually, Comet Hyakutake was discovered by an amateur astronomer in Kagoshima prefecture, Japan. He found it just two months before its emergence, so it’s not mentioned in the 1996 yearbook of that year’s astronomical phenomena. The comet emerged out of the blue and became a Great Comet before we knew what was happening.

I can imagine people in the past were startled by the unexpected appearance of a bright light in the sky. No wonder people used to think comets were a sign of bad luck.

Today, astronomical telescopes have made it possible for us to know in advance when a comet will show up. But in the times when comets were only visible to the naked eye, they emerged so suddenly that people would take them as a sign that something bad was about to happen. The oldest record of a comet in Japan appears in the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan). There is a record from A.D. 639 indicating that when a comet was seen, there would be a famine. As observation technology has advanced and comets have become better understood, the superstition that they bring misfortune has almost disappeared.

But scientific explanations have alarmed people, too. The Earth passed through the tail of Halley’s Comet in 1910. Shortly prior, it became known that the comet contained cyanide, which is very poisonous, and a rumor spread that it would suffocate all living things on Earth to death. According to what I heard, there was a rumor in Japan that there would be no air, and people bought up bicycle tubes and also practiced holding their breath in a water-filled basin. But in reality Halley’s tail was too thin to influence the Earth’s atmosphere.

Curiosity fuels my work

You are an expert on comets and meteors. What made you decide to study these subjects?

Comet ISON (courtesy: Michael Jäger)

Comet ISON (courtesy: Michael Jäger)

I was attracted to the fact that they were unpredictable. When the October Draconids appeared the year I was in the sixth grade, astronomers had predicted a meteor shower, but in the end it didn’t happen. This proved that there were things even professional astronomers could not know. And it meant to me that “knowledge” had a horizon, and that I could have a peak beyond it. I was so happy when I realized this, and I began to go out every night to look for meteors.

Later I became interested in comets, which are the source of meteors, because I learned that their behavior is equally hard to predict. Meteors are comet dust particles the size of grains of sand colliding with the Earth’s atmosphere, about 100 kilometers above the ground, at extremely high velocities. They flare and disappear in a few seconds. On the other hand, the nucleus of a comet typically ranges in size from a few hundred meters to tens of kilometers, so it is very different from a meteor the size of a grain of sand. But they have a parent-child relationship, because the grain-sized particles released from a comet become meteors.

You have long been involved in promoting astronomy. It was your idea that the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan should open its doors to visitors on a daily basis, wasn’t it?

Yes, it was. I wanted people to start paying attention to the starry sky, even if only a little. But I am not the only one. Many other NAOJ employees are hoping for this from the bottom of their hearts. Astronomy is a study predicated on curiosity, which has basically no social benefit. But it costs a lot of money to make a cutting-edge telescope, and the money comes from taxes. This is why we would like as many people as possible to know that astronomy is exciting, and that NAOJ is working on very interesting things. Except for the year-end and New Year’s holidays, visitors can freely tour anytime after registering at reception.

Finally, could you tell us about your expectations for JAXA?

I just told you that we are truly hoping that more people will learn about the fun of astronomy, and I am sure that JAXA staff are hoping for the same. I’m sure they love space, and enjoy their work, and feel a sense of responsibility. I imagine that they too want to convey their fascination with space to the public. Now the challenge is to find how this can be done. It depends on the flexibility of the organization you belong to.

At NAOJ, our work environment has sort of a homey atmosphere, and it helps the employees perform at their best. Some people may think this is only possible with a small organization, but I believe it’s not a question of the size of the organization, but of ingenuity. I believe change is possible when everyone is on board, regardless of hierarchy. I hope that JAXA is also an organization that allows individuals to grow and develop.

Related links: National Astronomical Observatory of Japan

Junichi Watanabe, Ph.D.

Astronomer, Deputy Director General, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, National Institutes of Natural Sciences

Dr. Watanabe received his Ph.D. from the University of Tokyo. Along with his observation research on small solar-system bodies such as comets and meteors, he has long been involved in promoting astronomy. As a member of the Planet Definition Committee of the International Astronomical Union, he created a new category, dwarf planets, and was instrumental in re-classifying Pluto as a dwarf planet. He is a professor at the Graduate University for Advanced Studies, and author of a number of books on space, including Omoshiroihodo Uchu ga Wakaru 15 no Koto no Ha (“15 Words That Can Help You Understand Space So Well, It’s Almost Funny”).