Q. What do you think of the new space policy that the United States recently announced?

There are actually several policies that have been announced since Mr. Bush has been President. There was a new policy on remote sensing; a new policy on positioning, navigation and timing satellites; a new policy on space transportation. The one that's gotten the most attention, and the one that I am personally most excited about, was the policy announced in January 2004, which made human and robotic exploration of the solar system and beyond the overriding purpose of NASA. This means that we in the United States intend, in partnership with other countries, to leave Earth orbit and once again explore, as we did during the Apollo period. It's my view that this is the right thing for a government space agency to be doing -- to push frontiers, to send people back to the moon, and then beyond. And then most recently, in October 2006, there was a statement of national space policy that's drawn a lot of attention because it is in somewhat bellicose language. It's in a kind of tough language about expressing U.S. interests in space, which is somewhat typical of the Bush administration. But it also has a lot of positive things about taking care of training the people to do good space work, of making sure our industries are healthy, and worrying about radio frequency interference, orbital debris. There are a lot of positive aspects. There's been a lot of attention paid to the somewhat negative, military space aspects of the program, and I think that's missing the major points.

Q. Do you think it's the right decision to replace the Space Shuttle with a rocket-type human space vehicle such as the ones used in the Apollo era?

NASA's next-generation launch vehicle Ares-1 (Courtesy of NASA)

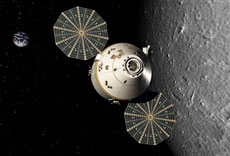

NASA's next-generation spacecraft Orion (Courtesy of NASA)

Astronauts on a spacewalk and a lunar rover on the lunar surface (Courtesy of NASA)

NASA's next-generation lunar lander (Courtesy of NASA)

One of the things that came out of the Columbia Board Investigation is that we recommended that the hauling of cargo into space and the taking of people into space be separated.

The new spacecraft being developed in the United States is called Orion. Orion looks a bit like a backward step, since it has the shape of an old Apollo capsule. Orion will be launched by a new rocket called Ares-1, which is also based on older technology, including a version of the solid rocket used by the space shuttle and an upper stage engine based on a rocket motor from the time of Apollo. But first of all, it's much bigger than the Apollo capsule. It can carry six people, instead of three, to the International Space Station, and four people to the moon. It sits on top of a rocket, which means that there's nothing that can fall off the rocket and hit it. It has an escape system, which the Shuttle did not. So NASA estimates it will be maybe 100 times safer to operate than the Shuttle is. And the safety of the crew is even more than ever the overriding consideration if you're going to put people in space. So this is a system for safely putting people into space, not for all the things that the Shuttle could do.

Q. Why is the United States trying to return to the moon?

I think the reason to go back to the moon is that it's the closest place to go. It is like an offshore island of the planet Earth, and it only takes three days to get there. When the United States went to the surface of the moon six times between 1969 and 1972, during the Apollo program, we only went to the equator of the moon and the side of the moon that always faces the Earth. So 85 to 90 per cent of the moon, we've never visited, and there are lots of areas on the moon to explore. Most people who are looking at the issue now think that one of the poles of the moon, probably the south pole, is a very interesting place scientifically, and that maybe there are resources there that can be developed for use in further space exploration. So the moon is an interesting object to study, and to do science from, and maybe to do economically productive activity. So those are the reasons to go back.

Part of the U.S. policy is to go to the moon using our own transportation system, but once we get to the moon, to invite all of the space countries and maybe even the non-space countries of the world to work together in lunar exploration and development. I know that a central feature of the Japanese vision for space exploration is development of lunar activities. And these discussions are happening all over the world, about going back to the moon, and what are we going to do when we get there? And how does that lead to further voyages? How much of the work there is relevant to preparing to send people to Mars? So I think it's a very exciting long-term prospect that's begun by the decision to go back to the moon.

Q. What is the potential for economically productive activity on the Moon?

There are two schools of thought about the economic value of activity on the moon. One I think is a bit extreme, but many people believe it. They say that there is a particular isotope of helium, called helium three, which actually comes from the sun. It's a byproduct of the fusion reaction that creates the energy of the sun, but it's embedded in the lunar soil. And if there could be an energy process that uses that for clean fusion energy, this could be the fuel for many centuries of energy on Earth.

I think a more realistic assessment is that we know there's lots of oxygen and a fair amount of hydrogen on the moon. Maybe it's in the form of ice, but certainly it is embedded in the lunar soil. If we can extract that oxygen and hydrogen, particularly oxygen, we can use it as fuel for rockets. One of the most expensive things about doing space exploration is carrying the fuel off the surface of the Earth. So if you could get fuel at another location more cheaply, it could be economically very valuable.

And there's a third thought that says you could make solar panels out of lunar soil, and capture the sun's energy, and beam it back to Earth for solar power, for use on Earth. The reason we go to the moon is to explore these possibilities, because we don't know whether they're going to work or not. We won't know until we go.

Q. What international cooperation including Japan should be considered for future moon missions?

I think the United States has made two things clear. One is that it is going to build the transportation system - the rocket, the spacecraft and the landing craft - to go back to the moon by itself. There is not going to be international cooperation in the transportation system. So to me that means it might make sense for Japan and Europe to cooperate with the other transportation system builder, which is Russia, so that there are two transportation systems rather than just one. I think that's a good idea.

Once we get back to the moon, the United States is working with 13 space agencies around the world, with JAXA being very much involved, in developing the broad purposes for going back to the moon and the things to do there. And out of that there will be decisions of what kind of equipment to build and eventually who's going to supply that equipment. Some will come from the U.S., some will come from Japan, some will come from Europe. The countries of the world, the space agencies of the world will work together in the process of lunar exploration 15 or 20 years from now.

| 1 2 3 4 5 |