Q. What aspects of the universe fascinate you? Has your impression of the universe changed since you started your research?

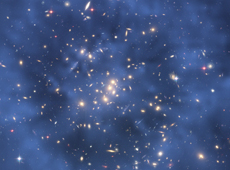

Galaxy Cluster Abell2218. Galaxies behind the galaxy cluster look distorted due to the gravitational lensing effect caused by the gravity of dark matter. (courtesy: NASA, ESA, Andrew Fruchter (STScl),and the ERO team (STScl + ST-ECF)

Galaxy Cluster CI 0024+17. There is a possibility that dark matter is spread in a ring outside the galaxy cluster seen in the center of the image. (courtesy: NASA, ESA, M.J. Jee and H. Ford (Johns Hopkins University))

What I like about the universe is its beauty. I am moved just by looking at beautiful images of celestial objects. I also like the fact that there is still so much unknown and so many mysteries. Beauty and mystery - I think the combination of these two elements is what makes the universe attractive to me.

Before I started studying the universe, I was under the impression that it was too vast and too distant to understand. I didn’t think it would be possible to gain a deep understanding of it because you cannot really go out and collect samples. But once I took up this interest, I realized that there is a way to investigate without physically going there, and it is possible to know so much. I think it’s quite amazing. On the other hand, the more I study, the more I am surprised to find how little I know. It humbles me. People must be surprised to hear that we know only about 4% of all the matter in the universe, and that the remaining 96% is still unknown. We know what a star is made of, but we have no idea what the universe is made of. Q. How do you think understanding the mechanisms of the universe would influence the general public? I think that just thinking about the universe is exciting and thrilling enough for those who are interested in learning about it. The fact that the universe has a beginning is a surprise in itself. Also, it is interestingly analogous to human life that a galaxy ages or is rejuvenated by a collision. But there is also a lot to think about for someone who is not inherently interested in the universe. For instance, thinking about the universe makes you realize how small human beings are. People in the past used to believe that the Earth was flat and at the center of everything. But science has revealed that the Earth is a globe - a planet that floats in the universe, orbiting the Sun, which itself is part of a solar system that orbits within our galaxy. And that there are many galaxies in the universe. As you find out these things, you can no longer think in a self-centered manner. I think understanding how the universe works inevitably has some impact on the way we think.

How is understanding the universe useful? It doesn’t improve our daily life directly, or prevent global warming. However, there are a number of cases where technologies developed for some kind of basic research have made indirect contributions in the areas of medicine or information science. For instance, the World Wide Web was originally developed for scientists to exchange data, but it is now almost ubiquitous across the world. And a simple question such as "how does the universe work?" can motivate the young generation to develop an interest in science or mathematics. There is now a great concern about young people’s dislike of science, but I think that learning about the universe will help change this trend, too.

Q. What do you think should be done to attract young people to science and mathematics?

Lecture at the Science Café (courtesy: IPMU)

I think it’s important to let them know how much we still don’t know, and inspire them to ask questions. As a child, I didn’t like the oppressive teaching style in school that forced children to memorize things just because they were facts. Whereas, if a school teacher says, "You have to learn this because it has been verified, but as far as that is concerned, we still don’t know for sure," I think children will wonder why this is so, and then will try to think about it for themselves. They may not become scientists, but it is a very natural thing for humans to have a desire to know. If we use a participatory educational approach rather than just stuffing children with knowledge, they will naturally develop an interest in science or mathematics, and an interest in unsolved mysteries. This is a key to get children excited.

With this in mind, the IPMU holds lectures for the general public; we run a science café to create opportunities for researchers and the public to mingle casually; and we have classes for schoolchildren. Likewise, we have had IPMU’s foreign researchers explain their research to local elementary school students, and we’ve held an event for high school girls. In addition, we make in-house journals and videos to publish on our website. I think one of the primary factors that keep people away from science is the unfamiliar vocabulary. To deal with this, we are making videos in which scientists explain technical terms. We would like to keep working on ideas for projects to get the young generation interested in science.

Related link: IPMU "Ask a Scientist" (currently available in Japanese only)

Q. What are your expectations for JAXA?

Next-generation infrared astronomy mission SPICA

Next-generation infrared astronomy mission SPICA

JAXA is the center of Japanese space development. I would like them to continue to provide dreams for people in Japan by training astronauts and carrying out wonderful missions such as the asteroid explorer Hayabusa.

And, although a large telescope, like the ones used on the ground, cannot be launched into space, astronomy satellites make it possible to conduct observations that are difficult to do on the ground because of the influence of the atmosphere. I expect that combining JAXA’s astronomy satellites and ground-based research will produce many new findings. For example, the x-ray astronomy satellite Suzaku (ASTRO-EII), which is currently in mission, has higher sensitivity than conventional x-ray astronomy satellites, and is capable of observing x-ray radiation coming from a thin, hot gas that pervades space. We know only about 4% of the matter in the universe, and even that 4% hasn’t all been observed. There is a form of matter called dark baryons. They are observable, but we don’t know where they are. Most dark baryons are believed to permeate space as a thin, hot gas, so they will likely be discovered by Suzaku. If we can figure out the distribution of dark baryons, I think this will lead us to an understanding of dark matter. So I have great expectations for Suzaku’s observations.

JAXA is now in progress on the next-generation infrared astronomy mission, SPICA, which will study the birth of galaxies, stars and planets in infrared. SPICA is a joint mission with the European Space Agency, but, reportedly, the United States is seriously considering participating as well. I am very much looking forward to the new discoveries that such an astronomy satellite will bring.

Related link: the next-generation infrared astronomy mission, SPICA

Q. What is your current objective?

My objective is to taste the joy of finding the answer. This hasn’t changed since I was a child. I was always full of curiosity, and loved thinking about why things are the way they are. I was fortunate, because my father was a semiconductor researcher and could answer my scientific questions right away. This is how I learned that every question can have an answer. Then I came to enjoy thinking further and further, "Then, what about this?" As my questions got more difficult, my father struggled to answer. But because I already had the sense from my childhood that there is always an answer somewhere, I was inspired to look things up on my own. And it was always a thrilling feeling as I got close to the answer. It was so great to experience the "I got it!" moment when my question was finally resolved. The joy I got from clearing my mind by finally understanding something is unforgettable. I do research because I want to feel this moment of satisfaction.