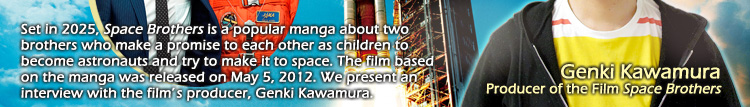

Genki Kawamura Producer, Space Brothers

In 2005, at the age of 26, Kawamura produced the film Train Man (Densha Otaku). Since then, he has had a number of box-office hits, such as Detroit Metal City. In 2010, two of his films, Confessions (Kokuhaku) and Villain (Akunin), were not only financially successful but got major recognition at overseas film festivals. The same year, The Hollywood Reporter named Kawamura the "Next Generation Asia 2010" producer, and in 2011 Kawamura became the youngest winner of the Fujimoto Award. His film, Love Strikes! (Moteki), was released in 2011, and he continues to have box-office success. He works in the Film Production Division at Toho Co., Ltd.

Q. What was your first impression when you read the manga Space Brothers? What inspired you to turn it into a film?

When the series started in a manga magazine in 2008, I read the first chapter and got very excited. I’m a big fan of space films, such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Right Stuff, and Apollo 13, and, as a filmmaker, I’d had a dream to make a space film myself someday. A space film is expensive to make, so it needs to be a mainstream film in order to attract a big audience. Accordingly, the story has to involve universal human drama. And in that sense, Space Brothers has an interesting contrast because it depicts a personal, small-scale human drama between brothers, but on the vast stage of space. Besides, I found it very charming that the boys’ ambition focuses on the largest stage of all. So I put in an offer for the film adaptation rights when the first volume of the comic book was published.

Q. The comic book is now up to volume 17, and the series is still going. Among the many episodes, what did you want to emphasize most in the film?

It was the first chapter. The story begins when the two little brothers, Mutta and Hibito, see a UFO and dream of going to space together. I wanted to articulate their thrill and excitement in a two-hour film. I didn’t intend to compress the original story by omitting the various episodes from the manga, but instead, my primary focus was to make the script show the process: how the brothers try to reach space. I wanted to depict how the dream and the promise the brothers make to each other in the first chapter turn out. Q. Did you have a theme in mind when making the film? My hope was to depict space as something people long for, and instinctively want to get to. I was interested in the reasons humans aim for space, but as I studied the history of the universe and met with astronauts in person, I came to realize that there is no real necessity for humans to attempt to get there.

For example, I asked astronaut Soichi Noguchi why he wanted to go to space, and he replied that it was out of his frontier spirit. I realized that, in the end, it’s all about desire - the desire to go and to see. At first, it’s just a simple desire to go to space - and only later is there a scientific reason or purpose, such as medical research, which completes the aspiration. I think what counts is not having a clear purpose but a notion like, "Astronauts are cool!" or "Wouldn’t it be interesting to go to Mars!" I wanted to deliver a message that, no matter what the initial motivation may be, those who have such notions are the ones who really try to make it to space.

Q. What age group were you aiming for with Space Brothers?

I’d like teens and twenties who are not interested in space to see it. Before starting to make the film, I actually did some research, and found out that most young people no longer dream about going to space. Of course some children are fond of space, but the majority are not interested in traveling there. So, for this film, I paid special attention to how I could attract young people to space.

During the Apollo program, when people witnessed the human lunar landing in real time, everyone dreamed about going to space. And after they returned to Earth, astronauts were treated like rock stars and paraded through towns to great applause. It was an era when everybody recognized that astronauts were cool. In Space Brothers, I wanted to recreate the atmosphere and mood of the time, so we made a pencil-shaped rocket, just like the one from the Apollo program. I wanted the film’s image of space to come from the era when everybody had a longing for it.

The opening of the film is a montage of footage from the Apollo era. For a cool effect, we made the opening like a promotion video, with artistic graphics and rock music. My intention was to show the audience that the space the brothers are going to try to get to is such a cool place. I wanted everyone to share that aspiration. I’m hoping the film will help kids who spend a lot of their time playing mobile games or reading manga realize how wonderful and cool space is. With this film, I’m extremely motivated to make an impact on young people who are not interested in space.

Q. What do you think is the most amusing aspect of Space Brothers?

First of all, it’s the montage of the history of space at the beginning of the film. The history footage itself looks like educational material, but I’d like the audience to enjoy how different it can look when presented in a different context. I find it fascinating that space can be so many things - it can be academic or it can be rock and roll. I’ll be happy if children and women, who generally have no interest in space, watch the opening and discover how wonderful space is.

I also want the audience to feel the powerful energy involved in humans going to space. I went to see the next-to-last flight of the Space Shuttle in February 2011. It occurred to me that the Space Shuttle was going to lift off carrying everything - not just the technology, but the time, feelings and energy that human beings had put into the launch - and that really touched me. Watching the launch, I was thinking, "it must be heavy" in so many ways. So in Space Brothers, I wanted to present a rocket as something that takes off carrying various aspects of human beings, rather than just as a physical object.

In addition, in the film, the moment Mutta gets a strong sense that his younger brother is really aboard the rocket, the rocket is no longer merely a chunk of metal but feels like a life form to him, and then he yells to the ascending rocket, "Go!" A rocket that is loaded with people’s thoughts and feelings does indeed look like a life form. Special attention was paid to making the rocket look like a living thing in CGI, as well as to the sound of the launch. I would love the audience at the theater to experience the great power of human beings in going to space.

Q. You were also keen about casting Buzz Aldrin, who really did go to the Moon on the Apollo 11 mission.

The director and I really wanted Mr. Aldrin in the film. The film starts with images from the Apollo era, and he also appears in the images. So by casting him in the film, we expected that the fictional world of the film would become real. Today’s young people may not know about the Apollo era, but I believe that the scene where Mr. Aldrin, who actually stood on the Moon, talks about going to space is quite significant.

Also, he was an astronaut of the Apollo era, when astronauts were treated like rock stars. The image of today’s astronauts is rather like scholars, but maybe because I am from the entertainment world, I prefer to depict astronauts like rock stars.

Q. What was the biggest challenge in making a live-action film out of the Space Brothers manga?

The challenge was that we could not go to the lunar surface to film in real life. The moment the audience becomes aware of a film set, their emotions cool down. So, by studying NASA’s footage from the Apollo program, we tried to make the set as real as possible. But then, no matter how realistic we made the lunar surface in CGI, based on NASA’s images, it still ended up looking fake. Making things look real more or less requires lies, such as cinematic lighting and star performers. We realized the importance of CGI. The fact that you cannot depict reality just by recreating it as faithfully as possible was a big dilemma for us. It was difficult to make the lunar surface look both real and attractive. Q. In the film, the Earth viewed from the Moon’s surface was bigger than in reality. Was this intentional, too? It was my idea to have a scene of the Earthrise viewed from the Moon. The size of that Earth is not realistic for sure. But that was the point. When we depicted the Earth at its actual size based on NASA’s images, it was not exciting at all. To me, films are not about reflecting reality but about reflecting the feelings of the characters, so I wanted the Earth to be enormous. I thought the feelings of Hibito, standing on the Moon, towards his older brother back on Earth, would be so big that the Earth would really feel that big in his mind. Expressing emotions in images is one of the beauties of film.

Q. From your perspective, how did the film turn out?

Personally, it is an important milestone for me because my dream of making a space film came true. This film has given me many exciting opportunities, such as filming at NASA, meeting Buzz Aldrin, flying our originally designed rocket in CGI, and building a set of the lunar surface. Throughout the production, the film also taught me about the pure beauty of humans going to space when there is no absolute necessity for it.

If my concept is right, I think this film could inspire some people to become astronauts. Today’s Japanese astronauts are certainly all the kind of people who can make an impact on a global scale. But as a result, they appear so elevated and special, standing far apart from the rest of us. But times are changing. I’m hoping for the emergence of a new type of astronaut, like an average-looking office worker, like Mutta, flying to space. And from the bottom of my heart, I hope that they are the ones who see Space Brothers as children and are inspired to become astronauts. I’ll be very happy if the film can inspire people to adore space.