Ryojiro Akiba

Born in Tokyo in 1930, Dr. Akiba was admitted in 1951 to the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Tokyo. He became a research assistant at the University of Tokyo in 1960, and a professor of the university in 1974. In 1981, he was appointed to the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS) as a professor, and became Director-General of ISAS in 1992. Dr. Akiba became a professor at Hokkaido Institute of Technology in 1996; a full-time member of the Space Activities Commission in 1998; Technology Adviser of the Institute for Unmanned Space Experiment Free Flyer in 2000; and President of the Hokkaido Aerospace Science and Technology Incubation Center in 2003. He received the Von Karman Award of the International Academy of Astronautics in 2008 and the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon, in 2011.

Q. How did you come to rocket research?

Ryojiro Akiba with the book Rocket Propulsion Elements

It was the influence of Prof. Hideo Itokawa. When I was a university student, I had to design a machine for a graduation assignment. But I was not very good at drawing, so I drew a small measuring instrument without giving it much thought, and handed it in. Then, at the preliminary review, I was scolded for the poor quality, and Prof. Itokawa, who was my advisor, said, “I’ll lend you this textbook on rocketry just for one night, so design a rocket.” I had no idea how to do it because people had never seen a rocket at that time. Besides, it was an English book, Rocket Propulsion Elements by George P. Sutton.

My English wasn’t good enough at that time to read the book, but I sat up all night anyway, trying to figure out the text, because I thought that otherwise I wouldn’t be able to graduate. And fortunately, I knew the mathematical formulas in the book, so I was able to understand the content by following them. The next day, I returned the book to Prof. Itokawa and submitted a rocket design. This was my first encounter with rockets. But at that point I still couldn’t imagine that I would become a rocket engineer. That didn’t happen until I decided to go to graduate school to continue research, and started assisting Prof. Itokawa. At my age now, I am forever grateful to him for having helped me shape my view of the world.

Q. So you met Prof. Itokawa when you were in university.

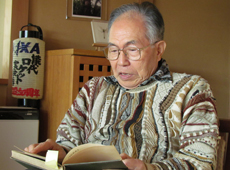

Ryojiro Akiba in his younger days, preparing for a rocket test launch

I happened to put it a request for him as my advisor, and he was assigned. I recall that his lectures were very interesting. His specialty then was medical electronics for electrocardiography and electroencephalography, so I didn’t know until later that he was involved in the development of the fighter aircraft Hayabusa before the war. Hayabusa was flying when I was in elementary school, and I used to long to be a part of it. I remember getting excited, imagining I would build or fly in such an aircraft someday. But later, Japan lost the war. I had a strong impression that Japan’s defeat was linked to technological capability, and my interest in technology greatly increased after the war.

I made up my mind never to commit military research, but I wanted to study aviation technology. With that aspiration, I entered a post-secondary school established under the former educational system, but in 1950 the school was abolished. Being out of school, I was loitering around without any vision for my future. As a bailout for students like me, the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (now the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology) admitted us to the second year of the University of Tokyo. That’s where I met Prof. Itokawa. So it feels to me that these coincidences, connected only by a thin line, guided me to the world of rockets.

Q. Professor Itokawa was originally designing aircraft. What got he involved in rocket development?

Horizontal test launch of the Pencil Rocket

Aviation research was banned during the post-war period, but when Japan regained its independence with the Treaty of San Francisco in 1952, the ban was lifted. However, the world was already entering the era of jet aircraft, and Japan’s aviation industry had fallen far behind. In the meantime, in 1953, Prof. Itokawa visited the United States for a couple of weeks to present his research on medical electronics engineering. And when he returned to Japan, out of the blue, he suggested that we develop a rocket, which the U.S. had just started doing. He thought we might as well try something new, rather than going after aviation technology, in which Japan was already behind. Mind you, his initial goal was not a rocket that would fly to space, but a rocket plane that could fly at supersonic speed in the upper atmosphere. So his Pencil Rocket project originally had nothing to do with space.

However, the situation changed on New Year’s Day 1955, when a newspaper wrote about Prof. Itokawa talking hopefully about flying from Tokyo to San Francisco in 20 minutes. Someone from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture came to him and suggested that we participate in an International Geophysical Year (IGY) event with his rocket. The IGY was an international scientific project that ran from 1957 to 1958, and one of its elements was to measure the upper atmospheric winds and temperatures using a rocket that could fly to an altitude of 100 kilometers. Prof. Itokawa decided to participate in the IGY, in collaboration with other scientists, and by the time the Pencil Rocket was ready for its flight test in April 1955, the goal was clearly set to develop a sounding rocket.

Q. Prof. Itokawa attracted scientists from various different areas. Why do you think they were interested in rocket development?

Group photo taken at a rocket motor static firing test in 1962. Hideo Itokawa and Ryojiro Akiba are sitting in the center of the front row.

I guess people are attracted to rocket development for different reasons. In my case, I liked the idea that I could make practical use of what I had been studying. I thought that I could see the world of rockets without studying a lot! (Laughs)

But, at the end of the day, what attracted us most was Prof. Itokawa’s strong passion for rockets. New things are invented not by groups but by individuals. It starts with one person’s will. Then the person get the people around them excited about the project, and persuades them to collaborate. To me, this is about the establishment of a new era.

The fact that Prof. Itokawa was working in electronics made it easier to attract experts from a wide range of areas in engineering. That is, the environment for comprehensive engineering support was already there from the beginning. And when he decided to participate in the IGY, the national government came through with a budget. So I think that many scientists joined not just out of curiosity but because the financial situation was favourable.

Q. Could you tell us more about Prof. Itokawa’s personality?

Hideo Itokawa with the Pencil Rocket

He was very quick and smart. Just by exchanging a couple of words, he always knew what you wanted to say. He was also a great judge of people. He seemed to be able to intuitively know each person’s capability and character. I think that when he told me to read the textbook overnight and design a rocket, he was testing me. I don’t know what he thought of my design, but maybe he realized that I was not the type of student who would whine about not being able to finish overnight. Prof. Itokawa was straightforward with everyone regardless of their age. So he was sometimes criticized by some older people, but he treated young people with a lot of generosity. Although he was 18 years older than me, he was always very nice to me.

Q. Are there any of his remarks you clearly remember?

There are too many to choose from. But, for example, in his lecture marking the 40th anniversary of the Pencil Rocket in 1995, he said that he had aimed to make a satellite the size of a kumquat. I think that, in the pioneer days of Japanese rocketry, there was no one else but him who was seriously thinking of launching a satellite 3 centimeters in diameter. Hearing that, I was again really impressed by the way he could think outside the box.

Q. What do you think were the main achievements of the Pencil Rocket?

I would say that the greatest achievement was the establishment of a rocket development structure. It brought together people who had studied rocket theory, and so to speak it started from scratch, with nobody knowing what to expect. Nevertheless, it gradually became clear what action would result in what consequence. For example, as you repeat experiments, you gradually learn how a rocket will spin, or how its flight path will bend, when its tail fin is turned. I think these were great discoveries for us scientists and engineers. I was still a student at that time, so my role was to just assist the others. But the experience of being there for the development of the Pencil Rocket taught me the importance of working as a team.

Q. Were you able to participate in the International Geophysical Year?

Hideo Itokawa with the Baby Rocket

We made it in September 1958, with the two-stage rocket Kappa-6. The IGY was held from July 1957 to September 1958, so we made it just in time. However, other than the United States and the Soviet Union, only Japan and the United Kingdom independently launched sounding rockets in this period, so that gave us confidence. The experience with the IGY gave a push to the further development of Japanese solid-fuel rockets, and gave us a new goal, to build a larger rocket that could launch a satellite.

But it was very difficult to build a rocket that could reach an altitude of 100 kilometers just two or three years after the horizontal launch of the Pencil Rocket in 1955. The rocket launch site was moved from Kokubunji, Tokyo, to Michikawa beach in Akita prefecture. As we moved to larger and larger rockets, from the Pencil, to the Baby, to the Kappa, the development of new propellant was particularly challenging. Every time we tried, there was an explosion. Many times we stood stunned, looking at the fragments of rockets. Even so, we did not give up. We just focused on moving forward towards our goal, and we were finally able to participate in the IGY.