No Reason to Turn Down the Invitation for Rocket Making

Yoshitoh Asari is a manga artist and the author of a number of science comics, including Manga Science and Natsu no Rocket. He has been collaborating on a private rocket-launch project. We asked him about the messages in his work and about private space development.

Yoshitoh Asari is a manga artist and the author of a number of science comics, including Manga Science and Natsu no Rocket. He has been collaborating on a private rocket-launch project. We asked him about the messages in his work and about private space development.

The Best way to watch a rocket launch is in person

What got you interested in drawing science manga?

What got you interested in drawing science manga?

Apollo 11 Lunar Module (courtesy: NASA)

Apollo 11 Lunar Module (courtesy: NASA)

Basically, I always liked science. My favorite books in my preschool days were illustrated reference books and encyclopedias. Also at that time, sci-fi shows such as Thunderbirds and Star Trek were on TV. And when I was in elementary school, there was the historic event of the moon landing, and the whole world was enthusiastic about space. This also helped me get interested in science.

What shocked me most was the real spacecraft, Apollo. Before the Apollo, the rockets I was used to seeing in sci-fi movies were all sleek in a streamline shape, but the Apollo moon lander was bumpy and uneven. This was because the lander was to be used in an air-free environment, so there was no need to worry about air resistance. The explanation was very convincing and had a great impact on me.

It led you to drawing rockets later on?

It led you to drawing rockets later on?

In the early 1970s, after the moon landing, magazines for boys would feature the Apollo mission, and sci-fi novels were also all about space. But there hasn’t been a space boom since then... Although the 1981 launch of the Space Shuttle generated some temporary enthusiasm, soon the interest cooled down, and people seemed to have already forgotten that humans had landed on another celestial body.

Being a manga artist, for the 20th anniversary of the Apollo moon landing in 1989, I spent a year drawing a manga about the history of rockets for an educational magazine. In 1992, the International Space Year, it was published as a book by Gakken, with the title Manga Science II: Rocket no Tsukurikata Oshiemasu (in English, “Learn how to make a rocket”). The manga showed rocket history from early development to human spaceflight, but astonishingly it was hard to find the necessary information. Even taking into account the fact that the Internet was not popular back then, it was very tough to gather materials. That is, there was no demand from the mass media, so images and documents were not made available to the public. This made me sad.

So later, I decided to take the opportunity of the launch of the Japanese-built large-scale rocket H-II, in 1994, and try to generate a space boom again. I had seen a rocket launch in person for the first time, and I was deeply moved. This inspired me to share the experience with other people.

How did you feel when you saw a rocket launch for the first time?

How did you feel when you saw a rocket launch for the first time?

Launch of an H-II launch vehicle in 1994

Launch of an H-II launch vehicle in 1994

I was surprised that watching the event at the site was totally different from watching it on TV. A TV camera follows just the rocket, but being at the site, you can see the blast of flames when the rocket lifts off in front of you. Also, the human eye can capture everything from extreme brightness to dark areas, but a camera cannot. So, in a camera image, when the exposure is set for the flames, the rocket body appears completely dark; and when the exposure is set correctly for the rocket body, the flames burn white and disappear. So to capture the scene with a camera, you have to compromise to a certain degree. And the sound – I mean, the shock waves. A microphone cannot capture the intense vibrations, which hit you deep in the stomach. A rocket launch is much more interesting when you see it at the site. It is absolutely different from what you imagine.

A Rocket is launched by “people”

So watching a rocket launch at the site is a totally different experience.

So watching a rocket launch at the site is a totally different experience.

Epsilon launch vehicle lifting off

Epsilon launch vehicle lifting off

I didn’t know anything about the location or the atmosphere at a rocket launch until I went to see the H-II rocket liftoff. The news cameras follow only the rocket itself. But when you go and see a launch, you can see the launch complex and the people who built the rocket. You realize that, after all, there are “people” who do this. And the launch isn’t everything. Other operations, such as satellite tracking and control, begin after launch. So many people are involved in a rocket project, and everyone’s task is important to making the rocket function. I didn’t fully understand this until I went to cover a rocket launch for my work.

Once I understood this, I started seeing rocket launches completely differently – they were more real to me. I had the urge to share what I felt with other people, so I travelled to see many rocket launches, even outside Japan, including the U.S. space shuttles. I also wanted to prove that anyone could go and see a rocket launch if they really wanted to. Actually, later, when I was on the ferry to Tanegashima Island, where there is a rocket launch complex, someone told me and said that he was on his way to see the rocket launch. I was very pleased.

On September 14, a Japanese solid-propellant rocket was launched, for the first time in seven years. Did you go to see the launch of the Epsilon launch vehicle, too?

On September 14, a Japanese solid-propellant rocket was launched, for the first time in seven years. Did you go to see the launch of the Epsilon launch vehicle, too?

The launch was postponed twice before it really took place. It has been quite a while since I went to the Uchinoura Space Center last time for the launch of an M-V rocket, but regrettably the launch this time was postponed, so I missed the event. However, it was very nice that there were more visitors than at the last M-V launch seven years ago. I was pleased by the festive mood and the increased numbers of visitors. In the 1990s, very few people came all the way to see it.

I have to do it if nobody else does

You are a member of the Natsu no Rocket Team, which develops private rockets. How did you get involved in this?

You are a member of the Natsu no Rocket Team, which develops private rockets. How did you get involved in this?

Group photo of the Natsu no Rocket Team (courtesy: SNS)

Group photo of the Natsu no Rocket Team (courtesy: SNS)

Natsu no Rocket © YOSHITOH ASARI/Hakusensha, Inc.

Natsu no Rocket © YOSHITOH ASARI/Hakusensha, Inc.

My dream is that Japanese people can go to space on a Japanese rocket. But launching a rocket currently costs billions of yen, which makes it unfeasible. In addition, there are no prospects for the development of an original Japanese manned spacecraft, so we cannot look forward to that for the time being. If things don't change, the future I have dreamed of will never come true. So I thought that there was no choice but for us to work to make it happen. I am not an engineer, so I assist rocket production mainly as a record keeper, and also by cutting pipes at the production location, for example.

When did you start doing this?

When did you start doing this?

In 1997, a group of people got together to discuss the possibility of building an original Japanese manned spacecraft using the H-II launch vehicle. And over the course of our meetings, we started looking at the possibility of designing a new type of launch vehicle with an existing rocket engine. So we asked Mr. Takafumi Horie, who was then president of an IT company, to invest some money for us to try to buy a Russian rocket engine. But the company tried to overcharge us, and we had to give up on that plan. It made us realize that, in order to avoid one-way negotiation, we needed to be able to build a rocket engine ourselves, regardless of whether we could make it work well. And, in spring 2005, we decided to really go for it.

The key member of our group in 1997 was a spacecraft engineer, Mr. Atsushi Noda, who worked for NASDA (now JAXA). We decided to bring to life the concept of a small rocket that I had suggested to him. I created a manga about that small rocket, called Natsu no Rocket.

Weren't the main characters of that manga elementary school children?

Weren't the main characters of that manga elementary school children?

Our rocket project is like grown-ups trying to make our childhood dream come true, and it's also like adults buying a toy we couldn't afford when we were children. I felt a little sad about that. But I thought that, in fiction, schoolchildren could build a rocket and launch a satellite on their summer vacation. So I contacted Mr. Noda to ask how big a rocket you'd need to launch a minimum-sized satellite. This later brought us together to actually develop a rocket.

Friendly competition

How is the progress of your rocket development?

How is the progress of your rocket development?

Liquid-fuel rocket Suzukaze, developed by the Natsu no Rocket Team (courtesy: SNS)

Liquid-fuel rocket Suzukaze, developed by the Natsu no Rocket Team (courtesy: SNS)

Launch of Suzukaze (courtesy: nvs-live.com)

Launch of Suzukaze (courtesy: nvs-live.com)

We conduct a test launch almost every six months and have tested six small liquid-fuel rockets. Our latest, Suzukaze, was launched in Taiki, Hokkaido, on August 10, 2013. The total length of Suzukaze is about 4.3 m, and it weighs 113 kg. In the launch test, its maximum altitude was 6,535 meters and its maximum speed, Mach 1.12 (380m/s). After launch, we retrieved the camera installed on the rocket and obtained the GPS recording as well.

Our near-term goal is to reach an altitude of 100 km with a single-stage rocket. If we succeed, it will allow us to move on to a multistage rocket that would carry a small satellite.

Are there any private rocket makers other than the Natsu no Rocket Team?

Are there any private rocket makers other than the Natsu no Rocket Team?

Hokkaido University and Uematsu Electric Co. in Akabira, Hokkaido, started before us. They are developing a hybrid rocket, CAMUI. CAMUI has not reached an altitude of 100 km, so we are sort of competing with each other in many ways. This competition is good stimulation for us.

So I am hoping that there will be many small teams like ours, and that they will push forward with their own strengths. Nowadays, many universities in Tokyo are conducting rocket-engine research, and Tokai University has carried out a test launch in Taiki. This field is becoming more and more interesting, and that's exciting.

Science is everywhere around us

What is the attraction of science for you?

What is the attraction of science for you?

To be able to learn what I didn't know before. I love the “wow” sensation I get at the moment I understand something. Science can explain why things around you are the way they are. People tend to have the impression that science is difficult because it involves many different mathematical formulas. But I want people to realize that everything in our daily lives is related to science, and that science is not something far from us, but is everywhere around us.

Is there anything you are cautious about when you draw science manga?

Is there anything you are cautious about when you draw science manga?

When I think of a story, I try not to simply explain or comment. I try to set a premise about “what is not clear.” Or, I deliberately lead with a false conclusion that people tend to fall for, and then flip it. I'm happy if readers can experience the pleasure of learning new things as they turn the pages.

Do you have any message, particularly for children?

Do you have any message, particularly for children?

I want children to feel the sensation of learning something new while turning the pages one by one. Instead of just being spoon-fed knowledge, you are given a hint, you're encouraged to speculate, and finally you find the right answer. I want them to taste the pleasure of figuring out something new. Finding out everything at once may be good, too, but I would like them to enjoy the process of solving something unknown to them step by step, rather than just memorizing facts.

It's fun to work towards a goal gradually, by maximizing what you can accomplish at any given moment. One example is space research. Despite the fact that our scope for observation is limited, people are trying to unveil things about space little by little within that scope. I want to show people the excitement of space research, and to continue to draw in manga that space research comes out of people's curiosity.

What kind of manga would you like to draw in the future?

What kind of manga would you like to draw in the future?

Asteroid Miners © YOSHITOH ASARI/Tokuma Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd.

Asteroid Miners © YOSHITOH ASARI/Tokuma Shoten Publishing Co., Ltd.

I would like to create manga with the message that our daily lives continue outward endlessly. For me, the basis for a manga story is people living their daily life. So the characters of Asteroid Miners are just ordinary people living on an asteroid. What I want to emphasize is that going to space is not something extraordinary.

We take our daily life for granted, but life would be impossible even if just one thing changed – if we lacked oxygen, for example. Conversely, as long as there is enough oxygen, it gives you a notion that humans can live anywhere. Through my manga, I would like to show people how it's going to be if we really start living in space. When people can imagine what life in space would be like, I think it will seem more realistic to them.

For instance, you may start wondering about having a sufficient supply of necessary resources and energy. The most practical solution will be to get those things locally in space. Taking this into account, the place where such resources can be expected to be available is an asteroid. The ultimate goal of our Natsu no Rocket team is reaching a near-Earth asteroid, or even the asteroid belt.

My belief is that humans are humans no matter where we are, even in space. Our lives must go on. I want to depict that realistically in my manga.

The Age of Japanese space discovery

What are your hopes for JAXA?

What are your hopes for JAXA?

I hope that JAXA will put humans in space soon. The time when Europeans explored overseas lands, between the mid-15th and mid-17th century, is called the Age of Discovery. Japan hasn't had such an era. Just like Europeans explored the oceans, I want Japan to attempt to explore space. The Japanese are an ideal race for a confined spacecraft (laugh). Because we are used to small rooms with low ceilings, I don't think that our astronauts will be uncomfortable being in a confined spacecraft for a long time. They may even feel at ease in such a space. Besides, doesn't it upset you that Japan hasn't been able to send people to the International Space Station on its own spacecraft?

It's because the country has the technology but cannot afford the cost of development.

It's because the country has the technology but cannot afford the cost of development.

I don't think so. After all, the biggest problem is that in Japan, when someone dies, people end up focusing on who to blame. When there's an accident, the investigation mainly tries to find out whose fault it was. As a result, people get intimidated before making a big leap. In the United States, on the other hand, when an accident happens, they immediately set about finding the cause. They think pragmatically – that if they can solve the problem, they can succeed the next time. So after an accident, instead of questioning everyone's actions, they allow people to speak openly, and they move forward as they clear the problem. Whereas in Japan, people clam up because they are afraid of being held responsible. So people tend to avoid trying anything that could result in an accident, and hesitate to be adventurous. The problem is, as long as you're afraid of a possible accident, you can never move forward.

A pathway to the future

Space exploration requires time and money. What drives you to work on rocket development?

Space exploration requires time and money. What drives you to work on rocket development?

It is definitely costly. I use my camera to record our activities, and pay out of my own pocket for the transportation to Hokkaido, where we do our development. Occasionally, I even buy materials for the rocket, but so do the other members. In spite of this, the reason I don't think about quitting rocket making is maybe that I would like to open a pathway to the future. Of course, I hope that we can successfully make our own rocket, but at the same time, I won't mind if the younger generation or another organization gets there first. I want to establish the fact that private citizens are also capable of designing and building rockets, and to make citizen participation in space a normal thing in the future. I think this desire is what's keeping me involved in rocket development.

I guess the important thing is to have a “just do it” attitude.

I guess the important thing is to have a “just do it” attitude.

Being invited to make a rocket, do I have a reason to say no?! To tell you the truth, that's my true feeling. I don't have any reason to stop making rockets.

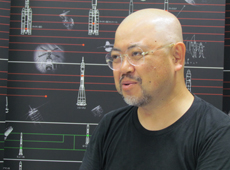

Yoshitoh Asari

Manga Artist

Born in Hokkaido in 1962, Mr. Asari made his manga debut with Jupiter Picket Line in 1981. His series of educational comics, Manga Science, started in 1987 and is still on-going. He is a rocket fan, and a member of the Natsu no Rocket Team, an organization that is attempting to design and build its own rocket. The project was documented and in 2013 published as a book, Uchu he Ikitakute Ekitai Nenryo Rocket wo DIY Shitemita, which means in English, “We made a liquid-fuel rocket by ourselves because we wanted to go to space.” He is the creator of a number of space manga comics, including Natsu no Rocket, Asteroid Miners, and Showakusei ni Idomu. He is a member of the Space Authors Club.