Hayabusa is a remarkable success story. It has made Japan a recognized world leader in space exploration. This was a great mission, very cleverly conducted. It's a wonderful example of the interaction between humans and machines, to be able to accomplish some of these dramatic engineering activities. There was risk to the spacecraft, risk during landing, the losing of contact, the gaining of contact. These were adventures that the whole world got to witness. And I think it's brought a great deal of respect for Japan as a major player in space exploration.

I think it may have a second impact, and that is that the Japanese public has become very excited about the drama of these missions and the results that are coming from it. I understand from just my visit here that the Japanese public is very interested in Hayabusa. Similarly, the American public has been very excited about Mars Exploration Rover, and the European public has been excited about Cassini Huygens. These are ventures conducted on Earth by people but in space by machines. And it may be that our unmanned robotic missions are going to be every bit as exciting as the human adventure in space.

I think Hayabusa is causing Japan to think about the role of scientific missions in public interest, public excitement, in education, in inspiration. And, I'm positive that this kind of boost to the Japanese program can result in good things happening in the future.

Q. The U.S. comet probe Stardust safely brought its sample home, but Hayabusa's outcome is still uncertain. How would you compare the two missions?

The Stardust mission and Hayabusa are a great example of why we have multiple missions from multiple countries, and the advantage of each doing something. When we look at the universe through telescopes, we're not satisfied with just one astronomer looking at one telescope. We have telescopes all over the world, and many astronomers participating.

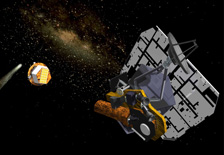

Exploration is a multidisciplinary, multicultural, multi-participant activity. And, Stardust going through the comet, capturing particles with the clever aerogel, and bringing them home was a great accomplishment. Another U.S. mission was Deep Impact, which sent a copper ball into a comet and caused an impact explosion, which brought off a lot of particles that could be measured, telling us about the comet's interior. And now Hayabusa, at the asteroid Itokawa, discovering this rubble pile - a very loose conglomerate that barely sticks together. These are interesting results. And it's like slowly putting a jigsaw puzzle together. You get a piece of information here, and here, and here, and here, and slowly a great picture emerges. Hayabusa, and Stardust, and Deep Impact, and the European Rosetta are getting pieces of the jigsaw puzzle for us to understand the small bodies, the asteroids and comets of the solar system.

Q. In the opinion of some foreign countries, Japanese space exploration includes too many things in one mission and expects too much. What do you think about this?

All space missions are a balance, because they are expensive. Even a low-cost mission costs hundreds of millions of dollars. It's expensive, and it's risky. So if you scale back your objectives, you find it very hard to accomplish a lot, because you don't get to fly these missions very frequently. At the same time, if you put too much on a mission, it becomes too expensive and too challenging. So it's always a balance. I think the Hayabusa mission struck the right balance. It worked very well. |

Japanese Asteroid Explorer Hayabusa

American Comet Explorer Stardust

American Comet Explorer Deep Impact |