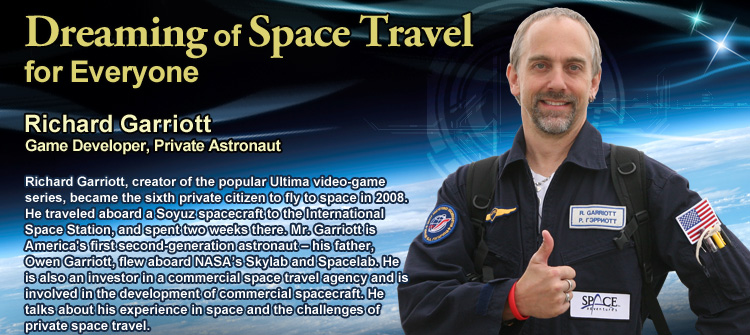

Richard Garriott

Executive Vice President of Portalarium, Co-Vice Chairman of Space Adventures, Ltd.

Born in 1961, Garriott began designing computer games while still in high school. In the early 1980s, he created the Ultima series of role-playing games, which remains one of the most successful and longest running franchises in entertainment software history, earning him legendary status in the video game industry. In 2006 he was inducted into the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences (AIAS) Hall of Fame.

Besides being a video-game developer, Garriott has also maintained a thirst for adventure and exploration. He has participated in two expeditions in search of meteorites on the continent of Antarctica. His other travels have taken him to deep-sea hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the Atlantic, and to Rwanda to observe mountain gorillas. In October 2008, Garriott realized a lifelong dream when he traveled aboard the Russian Soyuz spacecraft to the International Space Station, becoming the sixth private citizen to fly in Earth’s orbit. In doing so, Garriott followed in the footsteps of his father, Owen Garriott, who completed two space missions in his NASA career. They are the first American father-son astronauts. Garriott has had a passion for the space industry, and has invested in various related ventures such as the Zero-G Corporation, Space Adventures Ltd., etc. In 2009, in the United Kingdom, Garriott was awarded a Sir Arthur C. Clarke award for individual achievement. The prize recognizes achievements towards advancement in space exploration.

- The Urge to explore an unknown world

- Reaching space as a private astronaut

- First second-generation American astronaut

- Space flight was more than I expected

- A busy medical volunteer

- The Two best windows on the ISS

- Half a century after the first space flight, the space-flight era truly begins

- A Life-changing experience

- Reducing the cost of space travel

Q. Your private space trip reportedly cost $30 million. Why did you decide to spend so much money on this trip?

Richard Garriott boarding the Soyuz spacecraft (second from the top) (Courtesy of NASA)

Well, I helped start the company Space Adventures specifically so that I could find my way into space. And all of my investment in that company was towards the idea of reaching space, which is a desire I’ve had since I was quite young. So I knew even before we started that the price would be very high. And no matter what the price was, if I could afford that price, I intended to take this trip.

Why did I want to go to space? Because I like adventures into unknown worlds. Going into the unknown I find to be one of the most fascinating aspects of human possibility that I can imagine, whether that is exploring a cave in my own backyard in Texas, or exploring a rarely visited part of the Amazon jungle, or visiting space, or even visiting a virtual reality on a computer. I find all of those explorations to be similarly motivating.

Q. Did you have any fear about flying to space?

Of course, riding on a rocket into space and reentering the Earth’s atmosphere are both statistically somewhat dangerous. However, I felt particularly comfortable on the Russian Soyuz rocket, because that rocket has now had a track record of more than 30 years of safety. And each time they launch, they become more and more safe, I believe. So no, I did not feel particularly at risk during the space flight.

Q. You prefer being called a private astronaut, not a space tourist. Can you explain why?

In front of the simulator of the Soyuz spacecraft (Courtesy of Richard Garriott)

Black Sea survival training (Courtesy of Richard Garriott)

Some day in the future, there will be cruise ships that take passengers into space just like there are cruise ships that take passengers on the ocean. But today, every member of every spacecraft, including myself, is a complete member of the crew who is fully trained to operate all of the equipment and has duties to perform that allow that vehicle to travel in space. It’s just like on a military ship, where all of the members of that ship call themselves sailors. Whether they are the commander, or the engine operator, or the cook, all of them are still sailors. Similarly, every member of every spacecraft should be called an astronaut.

On the Soyuz, I was a fully trained astronaut. I passed all of the same tests and all of the same certifications that every other astronaut and every other cosmonaut had to pass. The exact same tests. And during flight operations, I also had to perform. The Soyuz has three seats, and I was required to perform duties in the third seat, just like every astronaut and cosmonaut before me. So I am almost offended when people argue that I am not an astronaut, because by any real measure I have accomplished all of the same goals and, I also believe, accomplished as much scientific activity and commercial activity in space as any other astronaut.

Q. Tell us about the training you did to prepare for this flight.

The Soyuz that I had boarded was launched in October, 2008. I began my preparations about two years prior to my flight. It began with medical preparations. I had to go through not only significant medical tests, but in my case, I also had to undergo surgery to remove a genetic anomaly within my body. As it turns out, I had something called a hemangioma – one lobe of my liver was fed by an artery that had no vein to drain it. I found out about that during my medical tests for my flight. And so I had an over-pressured lobe of my liver, which is quite common actually. However, in the case of space flight, if there was an emergency that included depressurization of the spacecraft, it might represent an easier chance to bleed, which you could not fix while you were in space, and so it would be fatal. So I had to remove one lobe of my liver as part of my preparation.

And then in January of 2008, I began to spend most of my time in Star City, Russia, where I underwent the same training that all astronauts and cosmonauts receive. So for example, I was trained in Soyuz operations: everything from how to operate the computers, how to operate the communication systems, how to operate the life support systems. And then how to perform my specific duties according to the flight data files of launch and reentry and orbital maneuvers. Similarly, I then had to learn the International Space Station operations. Again, operating the computers, operating life support, operating any emergency procedures, for example in case of fire or toxic atmosphere. Additionally, I had to learn all of the necessary requirements for all the experiments that I was going to perform. So that year of training was very intensive. I also had to learn the Russian language, so I now still know a little bit of Russian – enough to perform my duties and communicate with mission control.

And then at the very end of my training, myself and my crewmates had to pass oral examinations over two days that were required before we were allowed to board the Soyuz and to live aboard the International Space Station.

Q. It sounds complicated. Did you enjoy the training?

I enjoyed the training very much. I would actually say that the training was not particularly difficult, but there were many subjects covered. For example to understand the life support systems – keeping the oxygen and carbon dioxide in balance – is very similar to scuba diving. And so if you have a scuba diving license, you will find the course work in life support to be very familiar. Similarly, if you are a ham radio operator, which I am, you will find that the radio and communication operations on board the Soyuz and Space Station are also very familiar. If you are a person who enjoyed physics in high school, the orbital mechanics of a spacecraft are very basic Newtonian physics that you will find very familiar. And so the astronaut training I would say is very thorough and covers many subjects, but is not particularly difficult on any one subject.

Q. Your father was a NASA astronaut and flew in space twice. Are you influenced by your father?

Richard Garriott (left) on his return to Earth (Courtesy of Richard Garriott)

Richard and Owen Garriott, after Richard’s return from space (Courtesy of Richard Garriott)

Well it’s interesting. Of course I’m sure that my interest in space was influenced by my father – he was a scientist. My father never encouraged an interest in space, but having a father who was always involved, even at home, in his research about space, very much was a heavy influence on my belief that space was possible for everyone. But I have two older brothers and a younger sister, none of whom are interested in space.

Even when I was a very young child, I hoped and planned to one day travel into space. It was only a question of when and how I would get there. When I was five or six years old, I would ask my dad when he would come home from work, “Daddy, have you been to the moon yet today?” And of course the answer was “no, not yet today.” And so my fascination with not just space flight, but all of the science experiments that my father would bring home from NASA was very obvious truly from the youngest age, as young as I can remember.

And so there was no question in my mind that when I grew up, I would go to space. But there was one moment in particular when I think the decision solidified. When I was a teenager, one of the NASA doctors told me that because I wore glasses and had poor eyesight, I was not eligible to become a NASA astronaut. And it was at that age, approximately 13 years old, that I made the decision that since I wasn’t going to be allowed to go as a NASA astronaut, I would have to become a private astronaut. And of course there was at that time no such thing as a private astronaut. But at the age of 13 I decided that I would help build rockets, build space companies, and open the door for private citizens to fly in space, including myself. Which of course is what happened.

Q. Did your father give you any advice for your space flight?

He gave me advice, but it wasn’t much. I particularly remember a day when I was making one of my very last trips to Russia, and my father was dropping me off at the airport. And he came over to me and said, “Richard, you know, since you will be in space soon, I do want to just make sure that you remember that most people, when they reach orbit, go through a period of feeling very sick and very miserable and very unhappy about being there.” And, he said, “If this happens to you, don’t worry, because it really is only temporary. You will feel much better soon and it will be the best experience of your life.” I think that’s great advice.