Q. What is your current Moon mission project?

My main research topics are analyses of lunar formation. The science questions focus on the formation and evolution of the lunar crust, and the character and diversity of mare basalt types. I've been involved in lunar research for decades. I started, actually, as a lunar astronomer with various sorts of instruments that were being put on Earth-based telescopes. Now, technology and spacecraft capabilities allow us to send very capable instruments on a spacecraft to the Moon, and to study the global properties at high resolution. So it's much preferred to study the Moon with spacecraft data, because we can get data that are far superior. As I got involved in research, I started with my interest in the Moon and spectroscopy of the Moon. Spectroscopy is a technique for studying matter and its properties by investigating its emission and absorption spectrum using a spectrometer.

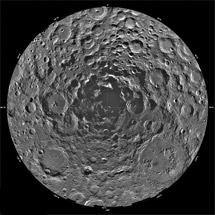

Lunar South Pole-Aitken Basin (Courtesy of NASA)

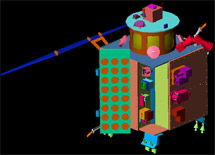

Indian Moon Explorer Chandrayaan-1 (Courtesy of ISRO)

For example, spacecraft spectral data are currently used for studying the characteristics and evolution of the lunar South Pole-Aitken Basin in detail. The South Pole-Aitken Basin extends from the South Pole of the Moon to the Crater Aitken on the far side, which is about, I think, 15° from the equator. One rim is at the South Pole, the other is near the equator. Many areas of high interest for this basin are about 1,000 or more kilometers from the pole, where the interior of the basin represents excavated material from deep within the Moon -- certainly from the lower crust, perhaps even the mantle of the Moon. Because this basin has not been filled with basaltic lavas the way most of the basins on the near side of the Moon have been, the character of the material excavated by the basin is still present on the surface of the basin. So by studying the middle of this enormous basin, we can examine aspects of the deep interior of the Moon, the lower crust and the mantle. So it makes geologists very excited about that opportunity.

Also, I am Principal Investigator for an imaging spectrometer built to characterize and map the mineralogy of the Moon at high resolution, called Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3 or “M-cube”). M3 will be flown on the Indian Chandrayaan-1 mission to the Moon in early 2008. When the Indians decided that they were going to launch Chandrayaan to the Moon, they identified their own payload, but they also invited payload from foreign participants. That was one of the first opportunities to fly the kind of instrument that I had been involved with to the Moon, so with that invitation to propose an instrument, my team submitted a proposal, first to the Indians. And when that was accepted, then we submitted our proposal to NASA for funding. The Indians have had quite a successful history in remote sensing, but principally they have concentrated on Earth satellites, where they have very extensive experience. The spacecraft they're preparing for the Moon is the first Indian mission that will go beyond the Earth orbit, so it's a new capability for them. Based on their experience with successful spacecraft, they are well prepared for this next step.

Q. What do you think of the Japanese Moon Explorer SELENE?

Well, the members of that project that I've interacted with, I've had enormous respect for. The SELENE mission itself is very exciting, and I'm eager to see it launched. I think it will provide some of the first data on a global magnitude that will be extremely exciting to the scientific community.

I'm very excited that over the next two years there's going to be so much international activity at the Moon with the SELENE missions, the Indian mission, the Chinese mission, and the U.S. mission. I think these next couple of years are going to be extremely rich, both for science and for exploration. And I'm absolutely delighted that these missions are happening around the same time.

Q. What do you think about international cooperation in lunar exploration?

I believe that international cooperation is very important, and not only in lunar exploration. I think every scientist is always eager to talk to other scientists. I understand, of course, that every nation needs to show its own capabilities, but I'm certainly hopeful that as we all proceed, we will take advantage of this excellent opportunity for peaceful international cooperation.

Q. What attracts you to your research? What do you want to know about the Moon?

I'm a planetary geologist, and planetary geologists want to understand how planets work. How the geology was formed and how it changes, how it evolves, what processes cause a planet to change. What's very exciting and uniquely available about the Moon is that it's almost pure geology. The Moon has no atmosphere, so it has no wind, no rain, none of that kind of weather that changes the geology. We don't have vegetation, we don't have plate tectonics. Instead it's almost pure geology, where all the geologic processes that have acted on the Moon are there to be read from the geologic record. And that's very exciting for a geologist, because it gives us a story that can be understood without the complications that we have, say, when studying the Earth or Mars. The Moon has maintained a record for billions of years, and it's for scientists to try to understand the mysteries that it presents us with.

Q. Are you interested in going to the Moon?

Oh, I would love to. I think everyone who's studied the Moon would love to. But I think we are going to be quite happy to allow spacecraft to do a lot of our job for us, and send the data from the Moon.

Q. Why are people interested in the Moon, and why are we going back to the Moon now?

My own perspective on that is that it's a long-term investment. If we accept that space exploration and space activities are going to continue in our society around the world, then the Moon is the obvious next step. I cannot tell how rapidly exploration of the Moon and Moon bases, etc. will continue. But it's clear it's a long-term investment. We don't know what resources are going to be most valuable, or most needed. But it's clear that the Moon will be one of the first places we, as inhabitants of Earth, look to.

Professor, Department of Geological Sciences, Brown University

Dr. Pieters is a planetary geologist who received her Ph.D. in Planetary Science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Her general research efforts include planetary exploration and evolution of planetary surfaces, with an emphasis on remote compositional analyses such as spectroscopy. Dr. Pieters has been a faculty member at Brown since 1980, after having worked for several years at the Johnson Space Center in Houston and as a Peace Corps volunteer in Sarawak, Malaysia. Dr. Pieters is the Principal Investigator for NASA's Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) experiment, to be launched to the Moon in early 2008, and also Co-Investigator on Dawn, a mission to explore the asteroids Vesta and Ceres. She is the Science Manager, NASA/Keck Reflectance Experiment Laboratory (RELAB). She belongs to several committees, including the Planetary Protection Advisory Committee, a NASA sponsored group to advise the Planetary Protection Officer on forward and back contamination issues.

Special Interview

>>Hitoshi Mizutani >>Paul D. Spudis >>Carle Pieters >>Wendell W. Mendell >>Bernard H. Foing

>>Lunar Explorers Around the World