![]()

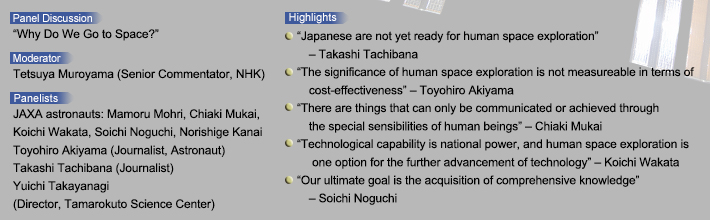

Muroyama: Today, we would like to have a discussion around a single theme: how Japan should move forward with space exploration. In particular, we would like to focus on human space exploration – Japan’s attitude toward sending humans to space and the question of what we will do there. Mr. Tachibana would like to raise an issue. Please go ahead, Mr. Tachibana.

Tachibana: To put it simply, I am against Japan conducting human spaceflight. It is better for Japan not to get into this. Japan is not prepared for human spaceflight. As a nation, the Japanese public is not capable of supporting it.

The other issue is about what we can gain by spending such a significant amount of money on space. When we think rationally about humans going to space, what has been done there, and what we have gained from it, I must say that there has not been much return to this point to balance out the money spent on space missions.

Toyohiro Akiyama (Journalist, Astronaut)

Soichi Noguchi (JAXA astronaut)

Chiaki Mukai (JAXA astronaut)

Takashi Tachibana (Journalist)

Koichi Wakata (JAXA astronaut)

Norishige Kanai (JAXA astronaut)

Yuichi Takayanagi (Director, Tamarokuto Science Center)

Tetsuya Muroyama (Senior Commentator, NHK)

Mamoru Mohri (JAXA astronaut)

Akiyama: I didn’t watch Yuri Gagarin flying to space on April 12, 1961, but learned about it in the news. His words then, “the Earth is blue,” had a great impact on us. I think it was a wonderful line, which gave us a sense that we are all on the same spaceship, Earth, regardless of whether we are friends or foes. In that sense, I am not sure it is fair to judge the significance of space exploration, especially human space exploration, based simply on its cost-effectiveness.

As to whether or not Japan can put up with failure, it takes practice. I believe that patience can be developed as you repeatedly experience frustration, failure, and not being able to achieve what you want.

Noguchi: I think there are things that we have to do for the future, for the people of the next generation, other than passing on the debt we have accumulated thus far. Either human space exploration is part of it or it isn’t. The fact is, we are leaving an enormous amount of negative baggage for our descendants. For that reason, at least, I feel that we are obliged to leave something positive as well – something that can inspire the children of the next generation.

Mukai: I am for Japan pursuing human spaceflight. Surely, in terms of national character, there is a clear difference in attitude between American and Japanese people. The Americans tend to keep moving forward, no matter what, with the pioneer spirit, while Japan is an island, and it tends to focus inward, which is how it came to develop transistors. Though the directions are different, I think the motivation comes from the same root, the desire to explore, to satisfy curiosity, and to make discoveries. So, Japanese people may not have the American attitude, but I think it’s fully possible to expand the scope of our activity even with the Japanese way of thinking.

Regarding money, I don’t think “all-or-nothing” is the right way to look at it. What is important is to do what we can now, for the future. No matter how small the project, as long as our eyes are on the future, it can generate power from within to live tomorrow. Money should not be spent recklessly on many things, but I think that Japan should conduct human spaceflight with a good sense of balance.

And what can we get from this? The issue that Mr. Tachibana raises comes only from a material point of view. To me, the great benefits brought by space exploration are not only physical, tangible things, but also something spiritual. I call these spiritual spin-offs versus material spin-offs. Space travel has helped us realize that the Earth is one, and that it is home to all of us. And each of us, Japanese or non-Japanese, is living as a human, hoping for a better life. We have taken other people’s happiness as our own happiness and other people’s sorrow as our own sorrow. It is difficult to assign a monetary value to such things.

Tachibana: Japan should choose a direction for its own space exploration within its means. The best approach is to focus on space robotics technology. Japan has far more advanced technology than the rest of the world in this area.

A good example of this is HAYABUSA. The whole system, the whole flight should be regarded as robotic. It was unmanned and didn’t cost very much money. Japanese technology achieved something almost miraculous by making such a great spacecraft and successfully returning it to Earth. I think HAYABUSA should be recognized as the pinnacle of Japanese technology. And so I think Japan should focus more on this direction. Even if Japan starts to work on human space exploration now, we will just end up chasing after the United States. Unless Japan can present a clear case for accomplishing a first in human space exploration, I’m still reluctant to see our country spending money in this area.

Wakata: It seems to me that, ultimately, “manned or unmanned” may be just a difference in methodology. I think that, first, there is an objective set according to the level of technology available in Japan, and then there will be a discussion of which methodology is best for the mission.

As we move forward with human space exploration, we must always be aware of the cost-effectiveness of the methodology. It is always important to consider what we want to accomplish, and then we need to be flexible in deciding whether a mission is manned or unmanned, depending on the circumstances. But at the end of the day, there is no doubt that it is humans, not robots, who take charge of science and technology. I think everyone will agree on that.

Safety is an extremely important issue. The operation of the International Space Station (ISS) is being monitored and controlled around the clock, every day, in the KIBO Mission Control Room at the Tsukuba Space Center. We don’t hear about it often because there have been no accidents. But, in fact, this is a truly difficult operation. If an accident resulting in injury or death happened on KIBO, JAXA’s competence would immediately come into question. Therefore, as far as the structure and design of KIBO and KOUNOTORI [the unmanned Japanese space cargo vehicle, which recently docked with the ISS] are concerned, we are actually already talking about human space vehicles. If there had been a collision, it would have been a major accident. We are extremely safety-conscious in our missions, so I think that we have already entered an era of human space exploration.

One other thing I would like to bring up is that I think technological capability equals national power. Technological capability involves not only technical aspects but also the human resources to support it. I think you can count these two elements – technology and human resources – as national power.

With space exploration – both rockets and human space exploration – I think that we have been able to build technologies that are highly trusted around the world. Taking space exploration to the next level is not something that can be done by just anyone – only by nations that are world leaders in science and technology. I don’t think it’s easy for any of these nations to afford to go to space. So if Japan is to continue to contribute to the world as a science-and-technology-oriented nation, in my opinion, space is an area that cannot be ignored. I also believe that when Japan sets out to further enhance space technology, human technology will have to be a significant measure of its success.

Kanai: We, the young generation, take it for granted that there are Japanese astronauts. It has become normal to have a Japanese astronaut in space. We are a generation familiar with Japan’s human space exploration because we grew up hearing about it on the news or somehow in our daily lives. The fact that young Japanese people can take such facts for granted is one of the byproducts of the work of the past 20 years.

Takayanagi: To begin with, I would like to point out that JAXA has done things differently than the world’s other space agencies. Astronaut Mohri was talking earlier about giving something back to society. When he made and swallowed that flower, which opened when immersed in water, on his first shuttle mission, it didn’t cost any money, did it?

Setting aside time in the astronauts’ very tight schedules, JAXA has been wonderful in showing children what humans can do in the unique environment of space, by carrying out a variety of interesting and inspiring space-based experiments, including space medicine experiments. I think that JAXA is probably the only space agency that has so brilliantly attempted to show what kind of place space is and what it means to us, and to make it seem more familiar and approachable for children and for people who are not scientists.

What I see watching children at my science center is that space exploration in their mind is ultimately human space exploration. I think it is very important at least to set an ambitious goal, and to ensure that Japan retains its technological capability, so that we can pass the baton to the next generation.

Muroyama: Let’s say Japan wants to carry our human space exploration on its own, using a Japanese rocket to launch a Japanese spacecraft, carrying Japanese astronauts, to go more than 100 kilometers into outer space to conduct some sort of mission. How far has Japan come to being able to do this in reality? I think that if it is just a pipe dream, we should drop it. How do you see Japan’s capability now?

Noguchi: I think Japan has the capability. I have three reasons for this. First of all, KOUNOTORI, which has already been launched successfully three times, didn’t carry people, but to my mind it is a manned vehicle nonetheless. It has safely delivered things to the ISS, and we are now working on the missing element – returning the vehicle to Earth.

Secondly, we have a system to support human space exploration on the ground. There are controllers, doctors and astronauts like us. Japan is developing its space capability comprehensively.

And finally, I think that what is required to support human space exploration is not only money but also the public’s understanding. I believe that various activities are contributing to building this support. It is about putting forward a positive vision of human space travel, including cultural and spiritual outcomes. I have no doubt that Japan has the ability to embrace this.

Mohri: Thinking objectively, Mr. Tachibana’s opinion seems to me to make a very good point about Japanese society today. Having a dream is a very good thing. Human space exploration definitely has a lot to offer for our future. But are we really willing to try, even if there is a strong possibility of failure? Will we as a society be able to get over it? I think we need to think it through more carefully.

I said this earlier in the keynote speech, but again, I suggest that you take a look at the control room at the Tsukuba Space Center. The staff are conducting very tough emergency preparedness drills because there really are people on KIBO. This fact should be made more visible to the public. I think we all agree that it’s going to take a collective national effort to strengthen Japan. It will take that kind of broad commitment. And I believe that the ISS, as a large-scale human space exploration project, gives us a chance to learn to do so.

The most important thing to remember is that human spaceflight technology, once put on the shelf, won’t be able to recover. Putting aside the question of when to start, I think what is important for Japan to consider now is how to pass technology on to the next generation without stopping. Other countries are scheduling Mars missions. Japan should make a move in advance and offer to collaborate. This will help ensure international security. And at the same time, while contributing Japanese technology to these international missions, we can develop it further. At the end of the day, I think the question is whether or not Japanese society can accept such a tough strategy.

Muroyama: I have a question for you, Mr. Tachibana. What do you think is the future value of human space exploration? What are the great things that are only possible for humans to do by going to space? Apart from the question of manned or unmanned, when humans use a high-level tool such as space technology, we may discover something that will eventually generate unimaginably great value. If that happens, is it thanks to human space exploration? Here is my question for you, Mr. Tachibana: is there no chance that human space exploration will possibly end up saving humankind?

Tachibana: I have written a lot about the benefits of humans’ going to space. To my mind, the greatest benefit is the fact that human beings are, in short, the most sophisticated sensor among all sensors that are capable of catching what is happening in this world.

When some representatives of the human race fly to space and tell the rest of us about their impressions, there is always something all humankind can sympathize with. On the other hand, when robots go and return, and the data they’ve collected is published, it doesn’t generate any sympathy at all. I think that only when humans go to space and report how they felt does it become possible to touch people, and this is a benefit of human space exploration.

A critical problem is that space is much more immense than ordinary people can imagine. Even if you want to explore space deeply, space is so big it can’t be measured with any existing scientific tools on Earth. When it comes to unveiling the mysteries of space, this topic is even more immense and requires a totally different approach. Many people tend to think that the astronauts we have here today are all JAXA is about. But this is not true. JAXA is also responsible for launching scientific satellites to study space, and JAXA’s space research is at a much higher level than most people know. If you learn a little more about it, you will find that this research is actually much greater than what the astronauts are doing. Findings about space that will be made with this kind of technology are way more important. I hope that decisions about how to spend the national budget take such a broad perspective into consideration.

Mukai: I think everyone has a broad perspective. I agree that space science is very important. But from my perspective, human spaceflight doesn’t have to be about sending people to deep space. As we expand the scope of our activity with the technology now available, what is most interesting about low Earth orbit is to be able to have a zero-gravity laboratory. I think that this is the greatest selling point of the ISS. Just as Mr. Tachibana has a dream about deep space, this is the dream of people who are doing science using the space environment. I expect that more of these kind of dreams will emerge.

And, after all, as we’ve said, there are certain things that only humans can do – things that involve feeling. I think that “sense” and “sensibility” are two different things. Although today’s robots can sense hot, cold, hard or soft, for example, they lack what we call sensibility. I think sensibility is at the heart of our motivation to expand the scope of our own activity, and space exploration can further this.

Wakata: I think international collaboration is not just about working together. It allows nations that make great efforts and have competitive technological capabilities to stand on an equal footing. This applies to science as well as to human space exploration. I think this is an area that only nations with advanced technology can participate in, and thus it is the responsibility of those scientifically advanced nations to play this role.