Asteroids are celestial bodies that orbit the Sun. Most of them are between Mars and Jupiter, but there are near-Earth asteroids, such as Itokawa, that come close to Earth's orbit. Scientists think that planets in the solar system formed from these small celestial objects, and if that's true, it may be possible to find clues about the birth of the planets and the solar system by studying asteroids such as Itokawa. After arriving at Itokawa in September 2005, the Hayabusa spacecraft conducted scientific observations for approximately three months, revealing to us various aspects of the asteroid.

Q. Could you tell us about the scientific achievements of Hayabusa thus far?

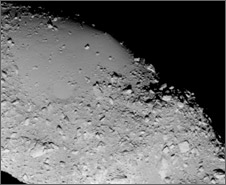

There are many large rocks on the surface of the asteroid Itokawa

The main feature of the exploration mission was to send Hayabusa to a very small asteroid. The size of Itokawa, from one end to the other, is about 540 meters, and this was the first time that a space probe traveled to such a small object, and even landed and took off from it.

The major scientific achievement was an assessment of Itokawa's interior structure. We found out that Itokawa's density is less than that of rocks found on Earth. We studied the types of rocks on the asteroid's surface with infrared and X-rays, and found out that there was a great difference between the density of the rocks and Itokawa's estimated density, calculated from its actual mass and volume. This means that the density of Itokawa is very low, which indicates there are a lot of gaps inside the asteroid.

We also discovered that the surface of Itokawa is totally different from that of asteroids we have seen before. For example, the asteroid Eros has many craters on its surface, which is 38 km from one end to the other, but on Itokawa we saw very few craters, and, instead, many large rocks lying here and there. I think this is a great achievement, as we now have a much clearer picture of Itokawa. Hayabusa acquired very useful and precious information that will allow us to study the circumstances around the time of the birth of the planets.

Q. How did your impressions of Itokawa change before and after Hayabusa's arrival at Itokawa?

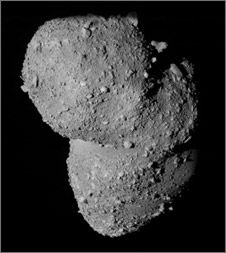

Itokawa in the shape of a sea otter

I imagined that Itokawa would have many craters, like other asteroids, but there turned out to be almost none. In fact, 40 small craters were found, but they appeared at first glance to be merely rocks, and are very different from the image we had previously. As for the shape of Itokawa, based on our ground-based observations, we had thought it would be like a thin potato, but it actually looks like a sea otter, with two large chunks fused together. After all, we cannot obtain accurate information about a celestial body unless we send a probe there.

Q. What's your theory of the formation of Itokawa?

It is thought that Itokawa was once part of a larger celestial body, which broke into pieces when it collided with another object. Some of these fragments are thought to have eventually impacted with each other and formed smaller celestial objects, such as Itokawa, which appears to have been formed from two such pieces. In fact, the existence of gaps inside Itokawa, which I mentioned earlier, is the very key to this theory that two asteroids collided, creating fragments that then formed Itokawa.

Q. Does Itokawa have gravity?

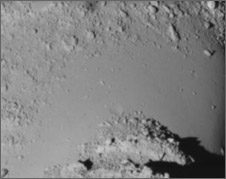

Itokawa's smooth terrain

It does but it is very weak. Itokawa's escape velocity is around 15 centimeters per second, so if you stood on the surface and jumped, you would fly away to outer space and could never come back again. Similarly, if a meteorite crashes onto Itokawa and stirs materials on the surface, they will escape to space because of the weak gravity. Some small stones and sand (regolith) have gathered around the “neck” region, between Itokawa's “head” and “body” regions (this area was named the Muses Sea by the mission team), to form a smooth terrain, while the head and body are rough, with many rocks. It is the first time we have seen an asteroid's surface that is not covered with regolith.

Q. What do you remember most vividly among Hayabusa operations thus far?

For me, it is the touchdowns on Itokawa. I was in charge of monitoring Hayabusa's velocity. The first attempt made us especially nervous, because the spacecraft wouldn't lift off even after the estimated time. We had no idea what was going on, and we were wondering anxiously whether Hayabusa had flown by Itokawa or whether its leg (the sampler) had gotten sunk in very soft regolith. But we learned later that Hayabusa had actually landed on Itokawa, and that, Itokawa's rotation somehow made the spacecraft appear to be in motion.

Itokawa looks like it's composed of two blocks

Q. What is the future research agenda on Itokawa?

The evolution of Itokawa will be studied in more detail with data analysis. Itokawa was originally situated in the asteroid belt, a little outside Mars's orbit, but the asteroid's orbit changed, and it started closer to Earth. We now know that the color of Itokawa's surface has been changed by space weathering, and that its shape might have changed at some point in its history, too. I think more research from now on will focus on Itokawa's evolution.

Q. What have you learned from the Hayabusa mission?

I have learned a lot. This was the first time anyone had attempted to operate a probe spacecraft under microgravity, so I was given a lot of opportunities to learn new things, including navigation. I'd like to use this valuable experience for the next exploration project. Also, speaking from a more scientific perspective, by closely observing an object as small as Itokawa for the first time, I was able to freshen my knowledge of small solar-system bodies.

Q. What is your dream for the future?

Asteroids are classified based on their characteristics. There are, for example, rocky S-type asteroids like Itokawa, and C-type asteroids that contain a lot of organic compounds. My major goal is to explore and investigate different types of asteroids. Also, I'd really like to see many celestial objects in the solar system that haven't been explored yet.

Q. Do you have a message for children who wish to be part of future space development?

Hayabusa landing on Itokawa (artist's rendition by A. Ikeshita and JAXA/ISAS)

The universe is still full of mysteries. I'd like you to challenge frontiers and make a lot of discoveries. So, to get you all interested in space, I'd like to create more opportunities for the public not only to learn through images or books but also to be able to come and observe our work on site.

Q. What do you think about Hayabusa's return?

Despite many troubles, such as the malfunction of the attitude control system, a battery discharge and a fuel leak, Hayabusa has made a comeback each time thus far. Fortunately, Hayabusa is still alive, and I'd like to see it complete its mission. Although the spacecraft is continuously struggling on its way back, I really hope it will make it. I'd like to bring it back home to Earth.

Doctor of Science. Associate Professor at the Department of Space Information and Energy of the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS)/ JAXA.

Dr. Yoshikawa graduated from the Department of Astronomy of the Graduate School of Science at the University of Tokyo. After working as a Research Fellow at the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), he joined the Communication Research Laboratory (CRL) in 1991. He has been with ISAS since 1998. Dr. Yoshikawa specializes in celestial mechanics, particularly in orbital analysis of small solar-system bodies such as asteroids and comets. He is currently engaged in research on orbit determination for satellites and planetary spacecraft. He is also interested in spaceguard, which concerns Earth's impact with celestial objects.