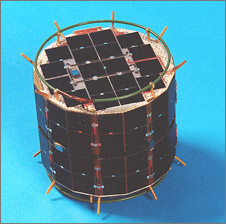

MINERVA (MIcro/Nano Experimental Robot Vehicle for Asteroid), Japan's first planetary exploration rover, traveled to the Itokawa asteroid aboard Hayabusa. It is a 16-sided prism measuring 12 cm in diameter and 10 centimeters in height, and weighing 591 grams. MINERVA was released from Hayabusa during its descent to Itokawa. It was designed to move around on the asteroid autonomously, by hopping, and to perform observations with a camera and thermometer. MINERVA was deployed on November 12, 2005, two-and-a-half years after Hayabusa's launch on May 9, 2003. Unfortunately, it did not make the landing on Itokawa. However, it was able to take an image of Hayabusa's solar paddle during deployment, which is the world's first image of a deep-space explorer taken from outside the spacecraft while in space. Maintaining stable function after release, MINERVA also succeeded in demonstrating many new engineering technologies.

Q. MINERVA is designed to travel by hopping. How did this idea come about?

Probing robot MINERVA

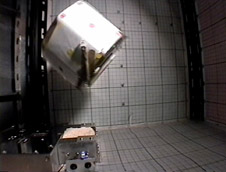

MINERVA's hopping experiment

Originally, Hayabusa was supposed to carry only a NASA rover, but in 1998 we initiated a project to develop an original Japanese one. Later, NASA canceled its rover plan, so MINERVA was the only one on board. We wanted to make our robot different from NASA's wheeled version, in part out of pride. We wanted to build an original Japanese robot. And after considering it theoretically and experimentally, we also came to the conclusion that a hopping transportation method made sense. No matter what direction MINERVA descends from, it can hop.

Q. What was the greatest challenge in developing MINERVA?

The first obstacle was the extremely low gravity on the asteroid Itokawa. Low gravity makes a rover hop no matter what, so with that in mind I came up with a design where the rover would move by hopping. It was necessary to make it hop horizontally because if it hopped only vertically, it would stay in one place. We tested the rover for direction and speed in a simulated zero-gravity environment, and also looked at its response on hard surfaces such as rocks, and soft surfaces such as sand.

MINERVA's data was to be transmitted to Earth via Hayabusa. But Itokawa is about 300 million kilometers from Earth, and it takes approximately 40 minutes for communication signals to travel back and forth between them. It's not very efficient if it takes that much time to send a command from Earth to Hayabusa and wait for confirmation of its receipt. So, we needed to make MINERVA capable of assessing its environment and taking action on its own, but the development of the software for this was very difficult. MINERVA is powered by solar cells on its body, which generate about 2 Watts of electricity. With higher computer processing speeds, more electricity is consumed, so we couldn't increase MINERVA's processing speed because of its limited amount of consumable energy. As a result, the performance of its onboard computer is less than one per cent that of ordinary, everyday computers we use. Adding many functions to such a computer caused delays and crashes, and we had a tough time solving these problems.

Q. What do you remember most vividly among all Hayabusa operations thus far?

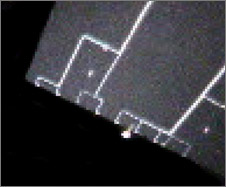

Image of Hayabusa's solar paddle taken by MINERVA

It's the deployment of MINERVA. MINERVA was released from Hayabusa during a rehearsal descent on November 12, 2005. A command was transmitted to Hayabusa to separate MINERVA, and I waited in front of the monitor to hear back from Hayabusa. Forty minutes later, the deployment of MINERVA was confirmed. I was so happy and informed everyone of the success. But three hours later we realized something was wrong.

Itokawa's rotation period is 12 hours. MINERVA should have landed on the asteroid around noon Itokawa time. The shift from noon to night there takes about three hours, and at night communication with MINERVA stops, as its solar cells cannot get any sunlight. However, the communication remained active for more than three hours, which indicated that the rover had not landed on Itokawa's surface. We learned from subsequent inspection that MINERVA had actually been released at a distance of 200 meters from the asteroid, instead of 70 meters. In addition, Hayabusa was flying away from Itokawa at a speed of 15 centimeters per second, which was the most severe problem. MINERVA might still have been able to make a landing, even from 200 meters away, if the probe had been moving towards the asteroid.

Even though MINERVA flew away from Itokawa without landing on it, stable communication lasted for 18 hours after the release. After communication stopped, I waited with the transmitter on for two weeks, just in case MINERVA sent a signal. However, in the end, no radio waves from the probe were detected. MINERVA had become the world's smallest satellite, at 591 grams. Its electronic devices may have been damaged by temperature fluctuations in the last year or so, but I still believe that MINERVA is alive somewhere.

Q. What went through your mind when you learned that MINERVA hadn't landed on the asteroid Itokawa?

I thought, “Well, that's life.” There was nothing much I could do about it. There were many stages to clear before sending MINERVA to the asteroid: making sure that the rocket launch would be successful, that the explorer would arrive safely at the asteroid, and that it would descend carefully. Then, it was finally MINERVA's turn. Each phase was challenging enough and carried a risk of failure. So, if MINERVA didn't go well, it didn't go well. I thought I'd start working hard again for the next goal.

Q. Did your impression of Itokawa change during Hayabusa's stay there?

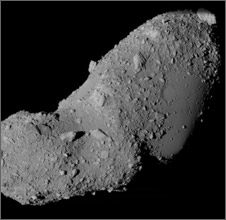

Asteroid Itokawa

Before arrival, I thought the surface of Itokawa would be relatively monotonous. But it turned out to have more variety, with sandy and rocky areas, for example. This confirmed for me that it was worth making a robot like MINERVA. If Itokawa had a monotonous surface, it would have been enough to perform a detailed study in just one spot, and it would not have been necessary to survey the surface by traveling over it. So when I saw Itokawa's surface, I was relieved that we had built a robot as mobile as MINERVA.

Q. What have you learned through the Hayabusa mission?

I joined the MINERVA research team in 1997, when I was still a graduate student, and got a job in 2000 at ISAS, the former Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (now JAXA/ISAS), as part of the development team. I got involved in Hayabusa after 2000. The Hayabusa mission is the first and only space exploration mission I've ever been involved in, so Hayabusa has taught me everything I know about space missions. Especially with MINERVA, there were many things we had to do by ourselves, and it gave me a sense that we were making a satellite with our own hands. Core parts of a satellite or an explorer are hard for us to build by ourselves, but it is possible for us to make a certain level of instruments, such as those used for observation, and in fact, that is what people at ISAS do. I realized that we should build what we can by ourselves, even if it's a spacecraft. I've gained some confidence in hand-crafting. I've also learned not to give up, not to compromise, no matter what, until the end, always trying to make the situation the best you can at that time. I think that space exploration requires creative ideas and pushing boundaries, and the Hayabusa mission has taught me the ideal way of working on a space project.

Q. What do you think about Hayabusa's return?

Hayabusa deploying MINERVA

(artist's rendition by A. Ikeshita and JAXA/ISAS)

I hope that propulsion by the ion engines, which is the initial step for coming back, will go well at first. But the return journey will take about three years, so we cannot relax for a while. As a member of the development team, I don't see that my agitation will stop soon. It will turn into joy if Hayabusa returns successfully, but I think that our trial will continue until then.

Q. What is your dream for the future?

I've been interested in robots since I was a child, so I'm basically keen on using them for unmanned exploration. I'd like to send various types of robotic explorers not only to asteroids but also to other celestial bodies, such as the Moon, Mars and comets.

Q. Do you have a message for children who wish to be part of future space development?

Space is surely easy to get interested in, but I don't think it necessarily has to be space. As a kid myself, I preferred robots and automobiles, if anything, to space. Whatever it is, I think it's wonderful for children to be interested in something that gets them using their own hands. Education reform and children's dislike of science have been issues of concern, but it's not easy to like science simply because you are told to do so. If children find it fun to work on things related to science with their own hands, their interest in science and mathematics will inevitably grow. So I'd like children to have opportunities to create things themselves.

Doctor of Engineering. Associate Professor of the Research Division of Space Information and Energy at the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS)/JAXA.

In 2000, Dr. Yoshimitsu graduated from the Department of Electronic Engineering at the University of Tokyo, and became an assistant professor at ISAS. He has been in his current position since 2003. Dr. Yoshimitsu specializes in robotics. He conducted research on an autonomous robotic system for exploring the surfaces of asteroids for his doctoral thesis, which was applied to the development of the small space probe MINERVA onboard the Hayabusa spacecraft. Dr. Yoshimitsu's current research includes next-generation exploration robots for small astronomical bodies and the Moon, and microsatellites.