![]()

Muroyama: The nuclear accident caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011 has changed the Japanese public’s attitude towards science and technology. In such circumstances, how can Japan step out into human space exploration? What direction does Japanese space exploration, including unmanned space exploration, need to take? We would like to talk about these topics today. How do you see things after the disaster?

Aoki: Sometimes people say that, after last year’s disaster, trust in science and technology has been shaken. But it is important to distinguish between technology and the systems to use and control it. I think what’s become apparent this time is people’s distrust of the latter. However, I think that, as human beings of each era have moved science and technology forward, our lives have been enhanced. Therefore, I think that we need to use science and technology to overcome the crisis we are facing now. For example, we can work on providing a source of clean energy by developing space-based solar power. I have realized that, as we promote science and technology, we need to develop a public consensus that we are moving towards a positive future.

Miura: After the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, we were questioned about science and technology. Or, not exactly about technology itself, maybe, but about the systems we rely on to operate technology, for example. I think there is a need to strengthen collaboration among industry, academia and government, and international collaboration as well, in order to re-examine our efforts in science and technology.

Muroyama: After the disaster, what direction do you think space exploration should take?

Nishimoto: What became clear during the disaster and its aftermath was how much space can contribute. For instance, at first, we couldn’t figure out why some of the floodwater brought by the tsunami didn’t recede even at low tide. After investigating with a positioning satellite, we found that the ground in those areas had sunk by as much as 70 centimeters. Also, when conventional telephone service was unavailable, satellite communication networks continued to operate. These examples confirm the value of space applications in ordinary people’s lives.

I think it is necessary to proceed with future space exploration, taking into account the value it brings to everyday life. It is also important to fully explain this to the public in advance. At the Office of National Space Policy, we are now considering the Basic Plan for Space Policy. In the process, there are discussions about how to balance the three pillars: 1) the advancement of science and technology, 2) industrial development, and 3) the enhancement of national security, including disaster prevention.

Ohtake: After the disaster, the National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP) did a survey of 2,000 people about their level of trust in and expectations for science and technology. The survey showed there was not much difference in their attitudes before and after the disaster. However, their trust in scientists went down. People may be feeling that they were betrayed by the experts, who used to talk only about the positive aspects of science and technology. I think this is an important lesson for us, and will influence the way we pursue space exploration in the future.

As pointed out earlier, after the disaster, satellites were extremely useful. I also heard that young people especially were cheered by the messages from astronauts in space. There is no doubt that space can be useful, attracts young people, and allows us to have dreams. However, I think that before implementation, experts need to explain the risks of space exploration and clarify what can be achieved. As for human space exploration, it will be difficult for Japan to go to space alone, so I think it is important to discuss Japan’s role in the framework of collaboration with other countries.

Muroyama: Professor Logsdon, how do you feel about these opinions of the Japanese panelists?

Logsdon: I think that space applications have become a necessity in today’s society. Although people are not usually conscious of the communications satellites and satellite navigation systems that they encounter every day, when a disaster happens they begin to really appreciate them. It is a chance to let people learn about what is going on in space, so I think it is important to have space applications always available for immediate use when a disaster happens.

Yakovlev: Russia is also making efforts in satellite applications for disaster management. To learn the status of a disaster as quickly as possible, I thought that international collaboration in sharing satellite data was effective.

Muroyama: The JAXA Astronauts 20th Anniversary Symposium was held the other day. At the symposium, I asked the panelists if they think Japan should conduct human space exploration, and those who were against it pointed out safety concerns and the cost issue. At the same time, those who support it argued that the expansion of the human spirit had value you could not quantify in monetary terms, and also that the technological and human capability demonstrated by space exploration are evidence of national power. Hearing these opinions, what do you think about the future of Japanese human space exploration?

Nishimoto: When the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster happened in 1986, the U.S. President immediately announced that a sad tragedy had happened but that the U.S. would continue space exploration for the future benefit of humanity. I was very moved. I felt the country’s strong determination to keep moving forward for the advancement of all humankind, regardless of the cost. But how would Japan respond if a similar disaster happened in our country? Frankly speaking, I don’t know if the government would be able to deliver a message that could earn applause from the public.

I think Japan has many opportunities to contribute within the framework of international projects such as the International Space Station (ISS), but it seems to me that Japanese society is not capable of supporting Japan’s own human spaceflight. In my opinion, Japan’s ideal situation in space exploration is to contribute to the world through its own specialties – technologies in robotics and autonomous control, as typified by the asteroid explorer HAYABUSA.

Ohtake: Whether or not Japan should conduct human space exploration on its own should be considered very carefully, but personally I am interested. I think that challenging the unknown is part of human nature. However, there is a big question about whether Japan is really ready to try human space exploration on its own. The Meiji Restoration opened Japan to the world after a long period of national isolation. Since then, the country has imported various things to catch up with and surpass foreign countries, and has become a major economic power. And now, it is said that it is time for Japan to try to be the first in something, instead of just emulating others. But when you are fighting to stay ahead of everyone else, you cannot avoid taking risks. I think the most important thing for Japan is to make the commitment. But such a commitment may be a challenge for Japanese society.

Muroyama: I was also one of those who were touched by the statement of the U.S. president after the space shuttle disaster. What are your opinions about carrying out human space exploration even at the cost of human lives?

Logsdon: The Columbia disaster happened in 2003, and I was a member of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board. In the discussion on how to handle the accident, nobody said that we should quit human spaceflight. The spirit to keep exploring the frontier of space is part of American society. People are aware that human spaceflight always involves risks, and the risks are inevitable, to a certain extent, for the nation and people who are involved in it. We know that there will never be zero risk, no matter how much we try to minimize it. This always applies not only to space exploration but to any cutting-edge activity. So, if Japanese society cannot accommodate this, it may mean that Japan is not a future-oriented society.

Aoki: I don’t think at all that Japanese space exploration would be stopped by a loss of human life. I’d rather believe that, when they experience a failure, people would have a stronger determination to succeed the next time. Humans were born in Africa and spread across the rest of the world, so it is a natural next step for us to go to space. I think Japan needs to play a part in this.

Miura: Japan has few natural resources and a small territory, and in addition, its GNP is slipping from third to fourth in the world. So I think what’s most important for the nation is the promotion of innovation – in other words, the promotion of science and technology. And in order to do that, I think it is necessary to work on human space exploration projects such as the ISS.

However, when we think about the future of Japanese human space exploration, I think it is important to start by remembering that our lives are granted by Nature. We need to think about how science and technology should be promoted in the environment, or in the civilization, where we do not live alone but coexist with plants and animals. If, upon reflection, we come to the conclusion that human space exploration is necessary, we can take that step.

Nishimoto: To me, regardless of whether it’s manned or unmanned, space exploration is a result of collective effort in science and technology. We also need to explore space in order to contribute to the future of humankind. Today Japan is a world leader in science and technology, but rivals keep emerging, so I think that we need to be proactive in investing in these areas. But it is also important to think about the objectives before implementation. The annual space budget of the United States is 4.5 trillion yen (about $60 billion), that of Japan is 300 billion yen (about $4 billion). With only one fifteenth of the U.S. budget, it will be impossible for us to try what they are doing. Therefore, I think that Japan needs to formulate clear goals, and carefully allocate the budget to achieve them.

Personally, I don’t think there is a need to focus on human space exploration when thinking about budget priorities. Japanese science satellites, such as astronomy satellites and HAYABUSA, are highly regarded around the world. They were made with the cream of Japanese science and technology, within our small budget, and have been able to produce wonderful results. As for human space exploration, before we move in that direction I think it is important to clearly explain to the public why we need to send humans to space, and to gain its support.

Dupas: The question of whether manned or unmanned is also discussed in Europe. However, for example, not everything on the ISS can be automated, and it is impossible to carry out experiments without astronauts. Of course there are things that only robots can do, but there are also things that only human beings are capable of. So, instead of comparing humans and robots, I think it makes more sense to have them complement each other. At the European Space Agency (ESA), the budget is allocated based on this theory.

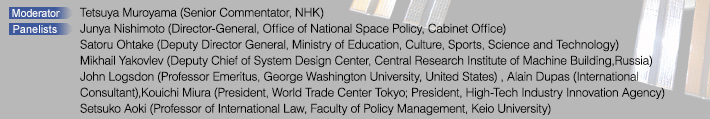

Tetsuya Muroyama (Senior Commentator, NHK)

Setsuko Aoki (Professor of International Law, Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University)

Kouichi Miura (President, World Trade Center Tokyo; President, High-Tech Industry Innovation Agency)

Junya Nishimoto (Director-General, Office of National Space Policy, Cabinet Office)

Satoru Ohtake (Deputy Director General, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology)

John Logsdon (Professor Emeritus, George Washington University, United States)

Mikhail Yakovlev (Deputy Chief of System Design Center, Central Research Institute of Machine Building, Russia)

Alain Dupas (International Consultant)