The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) is an independent administrative institution that coordinates official development assistance for the Government of Japan. The agency uses data collected by JAXA’s Earth observation satellites to plan its activities in the areas of forestry and conservation, water resources, disaster management, and cartography. We interviewed Kenichi Shishido, who is in charge of forestry and conservation projects at JICA.

Using space technology to protect the Earth’s forests

— Could you tell us about JICA’s forest-conservation work in developing countries.

Amazon

Amazon

About 70 percent of Japan’s land is covered by forests, so our country is quite advanced in terms of experience, knowledge and technology in forest management. When we help developing countries establish forest-management practices, we bring all that experience. In these countries, forest-management infrastructure has not been developed, because of a lack of technology and funds. This has allowed uncontrolled or illegal logging, and as a result deforestation has been accelerating. In fact, every year around the world, about 3,300,000 hectares of forest are lost. The decrease in tropical forests in Brazil, Southeast Asia and Africa has become particularly concerning. Forests absorb carbon dioxide, so protecting them is an important element of preventing global warming.

When we get involved in a developing country, we first map its forests. Based on these maps, we work with local staff to plan forest management and the utilization of forest resources. For example, we advise them on which areas can be safely logged by private industry, and which ones should be reserved for national parks. In developing countries, even establishing nature reserves is not a guaranteed solution. As the population grows, people need more space, and many enter reserves without permission, cut down trees, and start farming. In such cases, we work with local foresters to educate residents on the importance of forest conservation. In exchange for their respecting the boundaries of nature reserves, we sometimes make deals with them to help increase their agricultural productivity or assist with other means of income, such as livestock. We have different approaches depending on the circumstances in each country, but forest management is not possible without the understanding and cooperation of the locals.

— Has illegal logging in developing countries become a critical problem?

Illegal logging in the Amazon

Illegal logging in the Amazon

Satellite images being analyzed at the Remote Sensing Center in Brazil

Satellite images being analyzed at the Remote Sensing Center in Brazil

There has been a crackdown on illegal logging in all countries, but it is a difficult practice to stop, as sometimes large-scale organized crime is involved, and bribes are often paid to foresters and local police. In Africa, in the interest of forest conservation, an increasing number of countries are introducing bans on raw wood exports, so that only finished wood products can be sold abroad. But in reality, a large volume of raw wood from Africa is still being sold around the world. Deforestation is also moving quickly in the Amazon basin – hundreds or thousands of hectares of forests are illegally burned to create fields or pastures. If deforestation continues at the current rate, it will have a great impact not only on global warming but on biodiversity, as many unique species in those areas will become extinct. It will also affect the local populations more directly, as the frequency of large-scale floods and landslides will increase. For the profit of a small minority, what ought to be protected is not properly protected. This is the reality.

On the other hand, Brazil’s government has shown strong leadership, and has been making good progress. In 2004, it issued a presidential decree ordering the enforcement of anti-logging regulations. The Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources [IBAMA: Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis], working in partnership with the police, achieved dramatic decreases in illegal logging in the Amazon.

The satellite that was used to monitor the region at the time was a U.S. Landsat. The Amazon rainforest is more than 10 times the area of Japan. Monitoring from space is very effective because a wide area can be covered at once. But a Landsat satellite uses an optical sensor, which is not effective when there is cloud cover. And in the Amazon, the rainy season lasts half the year. So, knowing this weakness of the satellite, some illegal loggers would get to work when the rainy season came. Obviously, by the time the clouds cleared and the satellite could detect the logging, it was too late. Thus, when JAXA’s Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS, also known as DAICHI) was launched in 2006, there was a lot of international interest. ALOS was equipped with cloud-penetrating radar, so it could observe the Earth’s surface even through clouds. ALOS’s data made it possible to monitor illegal logging in the Amazon year round.

ALOS’s contribution to reducing illegal logging in Brazil

New logging detected by ALOS. Locations are indicated in red.

New logging detected by ALOS. Locations are indicated in red.

— For about three years starting in 2009, Brazil used ALOS to monitor illegal logging. Could you explain in detail how JICA and JAXA assisted with this.

We built a system that could immediately detect an illegal-logging site using data from ALOS. The total area of the Brazilian Amazon is about 3,500,000 square kilometers. It is such a wide region that to create an overview map, you need to synthesize about 300 scenes of satellite data. Once you have that map, by comparing images taken at different times, you can see where trees have been cut down. ALOS observed the Amazon every 46 days, and JAXA provided all the images to Brazil free of charge.

The data system was developed by the Remote Sensing Technology Center of Japan (RESTEC). After being approached by Brazil, JICA coordinated between the Japanese and Brazilian governments. We planned the project’s framework, and managed it, working with JAXA and RESTEC.

What was great about this project was that the Brazilian government and police cooperated from the very beginning. This became the key factor in their successful battle against illegal logging. Both IBAMA and the Federal Police received training in using the system. IBAMA is under the jurisdiction of Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment, and has the power to arrest illegal loggers. But the loggers can be heavily armed, so IBAMA has to work with police. When the ALOS data revealed an illegal-logging operation, local IBAMA officials and police would head there by helicopter to shut it down.

— What was accomplished over the three years of monitoring using ALOS images?

Clear-cut area in a forest discovered by ALOS

Clear-cut area in a forest discovered by ALOS

In Brazil, satellite data has been used for monitoring illegal logging since the 1970s, but with the introduction of ALOS, remarkable improvements were made. During the three-year project, starting in 2009, over 100 cases were identified, and the volume of illegal logging was reduced by more than half.

In addition to extracting the location, we built a system for finding the landowners by cross-referencing with land registries, in order to check whether the locations had been permitted for logging. We also developed a system to transmit the data immediately to the police. Making satellite data easy to visualize by adding information from land registries was especially appreciated, as it could be used as evidence in court.

As a matter of fact, I heard that Brazil was initially considering using data collected by other satellites, too, but they decided to go with ALOS because its L-band radar image showed the clearest distinction between forest and non-forest. Thanks to advanced technology from Japan, illegal logging in the Amazon was successfully reduced, but unfortunately the project ended in May 2011, when ALOS ceased operations. We are now discussing with JAXA the possibility of using its successor, ALOS-2, launched in 2014, to conduct similar monitoring of tropical forests in Brazil and other countries.

ALOS-2: the new standard in monitoring illegal logging

— In December 2015, the Initiative for Improvement of Forest Governance, a collaboration between JICA and JAXA, was announced at the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 21) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). How does this program use ALOS-2 to help developing countries?

Kenichi Shishido presenting the JICA-JAXA tropical forest monitoring system at COP 21

Kenichi Shishido presenting the JICA-JAXA tropical forest monitoring system at COP 21

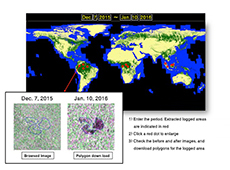

Forest Monitoring System website

Forest Monitoring System website

JICA and JAXA have teamed up to create a new forest-monitoring system using data collected by ALOS-2, which allows open access from around the world. It observes changes in the forest cover in tropical rainforests about every six weeks, with a resolution of 50 meters, and updates the data. The program’s web interface is currently under construction, aiming for the data to be available on the website of JAXA’s Earth Observation Research Center (EORC) around November.

This monitoring system will target 52 countries, covering almost all the tropical forests on Earth. The findings will be available not only to governments but also to businesses, NGOs and the general public. When we introduced the system to Japanese companies that own large-scale plantations overseas, we received a lot of feedback noting that it would also be very effective in preventing the theft of trees.

At the early stage, satellite images will be analyzed by visual interpretation, then it will gradually shift to automated assessment, which will provide better accuracy. We are designing the system to make the data easily accessible to anyone with a tablet or smartphone. You will be able to get information about the location of logging, updated every six weeks and displayed on a map on your device. With conventional systems, this kind of information is usually sent first to computers at forestry ministries, and then gets forwarded to ministry staff on site. Our new system, by contrast, cuts out that middle step, and makes the data available directly to local forestry stations, businesses and NGOs. So this will be a good tool to improve the transparency of forestry management, and also greatly reduce costs.

— What is your biggest challenge in building the new forest monitoring system?

ALOS-2

ALOS-2

I think that we will face many challenges once the system is in operation, but before anything else, the success of this project depends on whether JAXA can keep providing images for free.

JAXA is an institution that promotes research, development and applications in the field of aerospace. In the ALOS period, illegal logging monitoring in Brazil was still at the experimental stage, and it was carried out as a joint research project between JAXA and the government of Brazil. With the new forest monitoring system, however, we were informed that satellite data usage would be considered a practical application, not a research project, so JAXA is no longer involved and we have to purchase the satellite data from a supplier. For example, to make a complete map of the Brazilian Amazon, you need approximately 300 scenes. This means that one map will cost 90,000,000 yen (about 900,000 USD), so to update the map eight times in a year would cost a fortune. It is difficult for developing countries to pay such prices. Brazil was fully aware of the effectiveness of ALOS-2 data, but still had to give up the program for financial reasons.

But I could not let the achievements and experience gained through ALOS go to waste. Based on the results in Brazil, other Amazon countries, such as Peru and Colombia, as well as Southeast Asian and African countries, had expressed interest in using the same system, so I really did not want to disappoint them. After much exchange of ideas with JAXA, we agreed on a basic policy where JAXA and JICA jointly use our resources to make international contributions towards the prevention of illegal logging in all tropical forests. This announcement was made at COP 21 last year.

Continuous contribution from JAXA

— The key is “continuous” support, isn’t it?

JICA is promoting an international initiative called REDD+, to reduce the impact of climate change. It’s a program through which developed countries reward developing countries financially when they reduce greenhouse-gas emissions or increase carbon stocks through forest conservation. It is possible to measure the amount of carbon absorbed when you know the size of a forest, so satellite data is also used here.

Unfortunately, though, ALOS is used only as a complementary satellite in this program. The standard is a Landsat satellite. The reason is that NASA can provide Landsat data collected under the same conditions on a constant basis over a long period of time. In order to study the increase and decrease of the amount of carbon, you need to compare current data to past data obtained the same way. When data is not consecutive, it is hard to use. So I hope that JAXA will continue to launch satellites that can provide measurements non-stop. Once the forest monitoring system starts operations around the world, we are going to accumulate increasing amounts of empirical data. It would be such a shame to end the project when ALOS-2 ceases operations.

And I have one more request to JAXA, regarding the expansion of the provision of open data. Along side the United States with the Landsat missions, and Europe with the Sentinel missions, JAXA is providing lower-resolution images free of charge for the monitoring of natural disasters. I understand that satellite data needs to be analyzed and processed based on its use, and that the process is very expensive. But it is not realistic to charge such fees to developing countries, which are already in a tough financial situation, and I am worried that they may stop using JAXA’s data altogether. In addition to ALOS and ALOS-2, I hope that JAXA will continue making international contributions by collecting satellite data on a continuous basis for a long time to come.

— Finally, could you tell us your outlook for the future.

Global warming cannot be solved by Japan alone. Action has to be taken on a global scale. I believe that the new forest monitoring system will be an important tool for Japan to take the initiative and build the framework. I hope that the system will be introduced around the world, and that Japanese technology can help protect the Earth’s environment.

In addition, the Global Change Observation Mission – Climate (GCOM-C) satellite is scheduled for launch in fiscal 2016. There are discussions about using its data to detect forest fires. I find it a great honor to be able to contribute to the world with the technology JAXA can offer.

Kenichi Shishido

Deputy Director General, and Group Director for Forestry and Nature Conservation,Global Environment Department, JICA

After graduating from the Faculty of Agriculture of the University of Tokyo, Shishido joined the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in 1986. He worked at the headquarters and at the Indonesia Office, and also served as an officer for forestry. He became a Resident Representative of the Ghana office in 2004 and of the Sudan office in 2007, assuming his current position in 2013. He has published a book about his 1500 days of helping in the reconstruction of the disputed African country of Sudan.

[Sep 13, 2016 ]