The novelist Jin Mayama produces book after book that examines the light and dark elements of modern society, and challenges the hypocrisy behind ‘common sense’ views. Mayama’s work Baikoku (Treason), published in 2014, tells the story of a prosecutor from the Special Investigation Department of the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office who becomes involved in the murky world of the politics surrounding space development. Mayama says that in the course of his research for the novel, he did a lot of interviews with specialists working on space vehicles. JAXA cooperated with the production of a TV movie based on Baikoku, which aired in October 2016.

I wanted to give a shout-out to Japanese space development

— What did you want to say in your novel Baikoku?

Pocket edition of Baikoku (Treason)(© Bungeishunju)

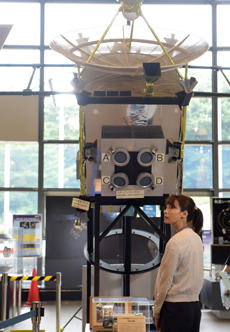

Pocket edition of Baikoku (Treason)(© Bungeishunju) Filming at JAXA. Saki Aibu plays the female scientist. (© TV Tokyo)

Filming at JAXA. Saki Aibu plays the female scientist. (© TV Tokyo)

The theme of this novel is the righteousness of the Special Investigation Department of the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office, and the dream of space development. The Special Investigation Department is responsible for pursuing consummate evil concealed in places that are hard for ordinary investigators to reach, such as political corruption. The public prosecutor from the Special Investigation Department who stands up to this great evil asks the question, “What is justice?” Meanwhile, there is a young female engineer who wants to launch a rocket that she has designed herself. The space program in which she has placed all her hopes involves technology that interests more people that just the State. What will become of her dreams when she becomes embroiled in political intrigue? I wrote about the nature of justice as well as how to protect hopes and dreams.

— The TV drama based on this novel, Great Evil Never Dies, aired on TV Tokyo on October 5.

The drama is fairly true to the original material, and properly portrays the themes of justice and dreams. In general, I feel that what ends up on screen is different from the original work, so I don’t ask that TV adaptations stick closely to my books, but I was impressed that this one managed to stay as close as it did to the original material. The unwavering pursuit of justice by the Special Investigation Department, and the potential that the human race will one day travel to space will surely be communicated to the audience.

I found the scenes showing the main character’s feelings about space particularly impressive, because they were filmed at the JAXA Sagamihara Campus and the Uchinoura Space Center. When they were filming at the Sagamihara Campus, I asked Hiroshi Tamaki, the actor who plays the prosecutor, what he thought, and he said, “The real thing is amazing!” Sagamihara has the feel of a university campus, except there are actual rockets on display, and it seems that he could sense that cutting-edge research was taking place there.

— It feels like the film allows us to experience the magnificence of the real thing, which so different from a film set.

Yes, I think so. At first I was worried about whether JAXA would cooperate with the production, because, as you can imagine from the novel’s title, Treason, the story features an engineer who tries to sell Japanese space technology to other countries. But what I wanted to get across with this novel was not just the simple question of whether or not the engineer was guilty of treason. In the end, I wrote the novel with the question in mind of how the Japanese space program could expand its potential even further. It is, of course, fiction, but if the space program had had a bigger budget, and if the potential of space had been more developed, the engineer would not have tried to go against the national interest. I wanted to make the point that I want more people in Japan to take an interest in space so that this kind of misfortune does not occur in reality. I wrote this novel because I wanted to support the people involved in the Japanese space program.

On-site research with a litany of surprises

— I heard that you typically spend a year to a year and a half doing research before you start writing. How did you go about learning about the space program?

Launch of the Epsilon Launch Vehicle in 2013

Launch of the Epsilon Launch Vehicle in 2013

I was able to talk to engineers involved in rocket development, including Yasuhiro Morita, the Project Manager of the Epsilon Launch Vehicle. Dr. Morita said to me, "As long as rocket launches are considered news, we’ve got a long way to go.” These days it has become commonplace to travel all over the world on airplanes, and a plane taking off is no longer news. He said the mission of space scientists is to open up an era in which sending people and objects into space is as ordinary as flying an airplane is today. He told me that we have to look more towards why we are going into space rather than just focusing on launching rockets, and I wanted to communicate that with my novel.

I also went to see the launch of the Epsilon Launch Vehicle in 2013, when Baikoku was being serialized in a weekly magazine. I saw both the launch that was aborted 19 seconds before liftoff, on August 27, and the successful launch on September 14. There were observation seats for the media that day, but I won a seat in the lottery that was held for the general public, so I chose to sit there instead, because I wanted to see everyone’s reaction. I still remember clearly when the first launch was aborted. There were no reserved seats, so I got there early in the morning to make sure I got a good seat, and I waited on tenterhooks for hours and hours, clutching my telescope. But the launch time came and went, and the rocket did not blast off. I found out from the press conference afterward that the launch was aborted because the rocket’s autonomous inspection system erroneously detected an attitude abnormality. But Mr. Morita said, “This was not a failure, as the computer detected a defect and automatically stopped the launch. This is a positive result.” Even reporters who would usually call this a failure voiced their approval. This reaction surprised me. And so did the reaction of the public.

— How did the public react?

On an oppressively hot summer day, I was waiting for the launch along with the rest of the general public, and I thought that some people would get angry when they realized that the launch they had been anticipating for hours and hours had been aborted just before liftoff. But as far as I am aware, despite the conditions, no one got angry. The reaction was that there would be another opportunity in the future, and that surprised me.

Project Manager Yasuhiro Morita (left) directly after the launch of the Epsilon Launch Vehicle

Project Manager Yasuhiro Morita (left) directly after the launch of the Epsilon Launch Vehicle

Then I went to watch the second launch attempt. The seat lottery for the general public was only held once, so the same people gathered to watch, and even though it was now September and the new school year had started, almost everyone came back. I saw these strangers, who had come from all over the country, exchanging photos of the first launch, which they had all attended. I was captivated by the strong feelings these fans had for the space program – feelings of understanding and support. I would have liked people who call the space program a waste of taxpayers’ money to see this. I want them to know more about the importance of space development. It was with this in mind that I wrote about the Epsilon launch.

— Your detailed description of the Epsilon launch day was impressive.

The first thing that Dr. Morita said at the press conference after the successful launch was, “Congratulations, everybody. I’m really pleased that Epsilon has launched.” At first I thought I had heard him wrong. But he clearly turned to all the staff and paid tribute to them saying “thank you” and “good for you.” He took sole responsibility for the initial launch postponement, and shared the joy of success with staff, media and space fans alike. I was impressed – this is a project manager. My novel is fiction, but I wanted to reproduce what I learned through my on-site research as truthfully as possible, so I included Dr. Morita’s comments in the novel.

Space can become a growth industry

— Weren’t you originally planning to write about the aviation industry rather than rockets?

Jin Mayama observing filming at JAXA(© OFFICE MAYAMAJIN)

Jin Mayama observing filming at JAXA(© OFFICE MAYAMAJIN)

That’s right. I was preparing to write the novel around the time that the news broke about the first Japanese-made passenger jet, MRJ [Mitsubishi Regional Jet], and I thought of a plotline in which the advanced nations of the world are flustered by Japan’s serious foray into the aviation industry. But I found out that in the United States there is a rule that foreign manufacturers must apply for approval of design drawings for aircraft that will fly in the nation’s airspace. And that meant that my outline did not stand up to scrutiny because even if Japan built a new airplane, all the technology would be leaked to the U.S. And then, right when I discovered this problem, a student who was working for me in my office and who was knowledgeable about aerospace, suggested that it would be interesting to write about space. He lectured me for hours, and taught me that there are many things in Japanese space technology that cannot be imitated by other countries.

Initially, I had negative feelings about the Japanese space program. Every time I saw news about Japanese astronauts going into space, I thought the only objective of these missions was the act of going to space itself. I didn’t see the results, and thought it was a waste of money. But as I talked to people involved in the field, I came to understand that in fact, space development would become one of the few growth industries in Japan. That’s when I decided to focus my novel on space.

— You also did research in the U.S. How did that go?

I felt a big difference between the U.S., where space development is already an industrial enterprise, and Japan, where it is still at the research stage. I was able to speak to specialists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory; they are always thinking about how they can use their technology in business. This comes from the style of education in the U.S. For example, it is considered completely natural at U.S. graduate schools that research labs are closed if they do not produce profitable results. This is not limited to space science; students work hard together to come up with ways to monetize the research produced by their labs. They are not only clever; they also continually think about business. Students who can show discipline in this way do not just come from nowhere; they need to be trained from high school onwards. To teach Japanese students and researchers to think about industrial enterprise, we need to review the education system as a whole.

Furthermore, I think the concept of failure also being a result has taken root in the American space program. I may be going too far, but I think that to them, a mission is a kind of experiment. In contrast, in Japan there is a sense of despair, in that if a mission fails, there will not be another. Not to mention the fact that Japan’s budget for space is one tenth that of the U.S. There is pressure to conduct research under extreme conditions in which failure is not allowed, with a thoroughly squeezed budget. But it’s normal that research and development achieves success only through repeated failure and trial and error. Consequently, I believe that Japan once again needs to acknowledge that it has been a world leader in science and technology all the way to the present day.

Better opportunities for young scientists

— What do you think we should do to improve Japanese space technology?

We shouldn’t get too hung up on results, and we should give more opportunities to young researchers. When I asked the young scientists or engineers I interviewed about their dreams for the future, they happily talked about wanting to research warp engines, or to become the first space architect in the world. Meanwhile, the reality seems to be that they are overwhelmed with administrative work and cannot manage to secure enough time for their research. And there is not enough funding. There is no way that Japanese space technology can evolve if we continue like this. Because it’s difficult to obtain investment from private companies if the results are not immediate, the State allocates a budget and backs research by young scientists or engineers. We need to create an environment in which they can study freely and concentrate on research. I think it’s important to have ideas about how young people can continue to make good use of their outstanding talents. And we also need outstanding “producers.”

— What do you mean by producers?

People who can appraise a variety of cutting-edge technologies and raise funds. In other words, a producer is someone who can ascertain whether a technology has the potential to make money in the future, and can raise the funds to develop it. They would also need presentation skills to be able to get funding from investors. If the government gave subsidies to these kinds of outstanding producers, they would be trusted, and would be able to attract even more money. I feel that Japan still has a long way to go – rather than investing in key people, it continues to invest in objects. With regard to these key people, in Japan we tend to think that 10 out of 10 people must succeed, but in actual fact, it’s fine if one out of 10 succeeds. In other words, it’s OK to have nine failures out of 10, as long as the tenth one is a success and is the best in the world.

After all, if we are going to make something new, something competitive, we need generous investment. Either way, we probably need to make sure that the Japanese people have a better understanding of the need for space development. As I said before, initially I didn’t know much about the Japanese space program, and I had negative feelings towards it.

Going into space is a reality

— How do you think we can encourage people’s interest in space development?

We need to get rid of the old idea that space exploration is a dream. Today going into space is a reality. Space is a new frontier, and I believe we should explain to people, in easy-to-understand terms, about this modern world that offers new business opportunities.

We change the way we speak to people depending on whether they are friendly or critical towards us, don’t we? It’s the same with space development. Not everyone is favorably disposed towards space, so you can’t talk to everyone on the assumption that it is something they like. I think in some cases it would be better to explain the missions more carefully, in order to connect with a critical audience.

— Don’t critics feel the attraction when we talk about dreams?

Today’s young people are realists, and few of them have dreams. It seems that they even think of people who talk about their dreams as reckless. They admire people who single-mindedly face up to reality, who repeatedly fail and pick themselves back up without losing heart, and who work towards their goals. They say they want to be like that when they grow up. So I think it would be better to tell the truth about how much research and how many failures go into developing technology, so that more people are moved by the effort that goes into it, and become interested in space development. We should focus on the real world rather than on dreams.

— Tell us about your future aspirations.

I want to keep writing stories that make readers want to keep on trying and become more positive. In my novels, I create professionals, I fully respect them, and I cheer them on. By “professionals” I mean people who have experience with technology and knowledge, and who can take responsibility in the end. It’s a shame, but there are fewer and fewer people like that in the real world, and that’s what has made Japan weak. This is precisely why I write about true professionals, and I think it would be good if people, in particular young people, wanted to be like them. During my research for Baikoku, professionals working in space programs helped me greatly. I hope that this dramatization will give not only my readers but also the people who see these images an opportunity to take an interest in space. I would really like to incorporate space development as a theme into one of my future novels.

Jin Mayama

Mayama graduated from the Department of Political Science at the Faculty of Law at Doshisha University. After working as a newspaper journalist and a freelance writer, Mayama made his debut as a novelist in 2004, with Hagetaka (Vulture), a human drama involving corporate acquisitions. That novel was adapted for television and aired to great acclaim in 2007. Mayama has written a great many other works including: Magma, Beijing, Corruptio(Corruption), Can You See the Sea? and Tokakushi (The Kingmaker).

[Nov 30, 2016 ]