What I learned while living in space

— Last year, you became the representative of the newly launched Living in Space research project. Can you give us a brief outline of the project?

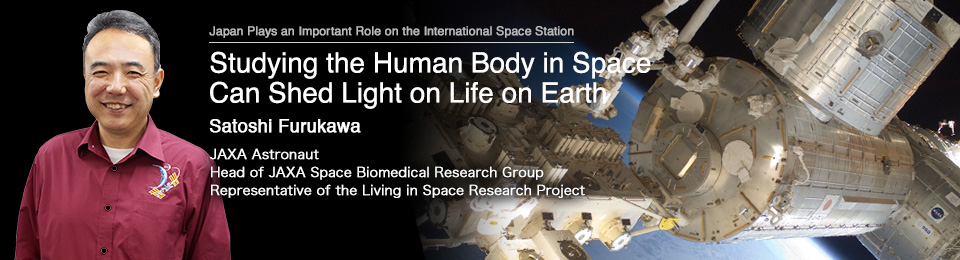

International Space Station (courtesy of JAXA/NASA)

International Space Station (courtesy of JAXA/NASA)

Astronaut Satoshi Furukawa during his long-term stay on the ISS (courtesy of JAXA/NASA)

Astronaut Satoshi Furukawa during his long-term stay on the ISS (courtesy of JAXA/NASA)

The Living in Space project was established and is supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. It’s a five-year project, running from 2015 to 2019. Space is an extreme environment for us Earthlings. While we’re there, we are affected by three elements: weightlessness, a closed environment, and radiation. This project comprehensively studies how these three elements affect the human body. In addition, we hope to maximize our achievements by integrating the results of space medicine experiments performed on the International Space Station.

— What led you to establish this project?

I lived on the International Space Station (ISS) for five and half months in 2011, and experienced various physical changes first hand. Since training for long-term zero-gravity conditions is not possible on Earth, there were many things we discovered once we got to space. So much was new and surprising to me. At first, I experienced space sickness and could feel my body fluids shifting. I felt bad for the first week – it was like having motion sickness constantly. My body fluids, including blood, moved towards my head, and my lower body became thinner while my face swelled up. I felt like I was constantly doing a handstand, and I felt heavy pressure inside my head.

There were many other things as well. Since the ISS is a closed environment, stress builds up. Microorganisms grow differently than on Earth. On Earth, humans, animals, insects and plants all coexist, and microorganisms are also deeply integrated into this ecosystem. In space however, since there are only humans, not only do the microorganisms in the human body change, but so do pathogenic microorganisms. In addition, without gravity load, bone density decreases, and muscles atrophy if you don’t exercise. And finally, exposure to radiation in space is dozens of times greater than on Earth.

When I returned to Earth, I had a hard time with gravity sickness. Because my body had adjusted to zero-gravity, I lost the sense of balance we have in a gravity environment on Earth. I felt especially sick when I turned my head – it was a really strange sensation. This experience made me realize that the biological risks in space – such as zero-gravity, stress and radiation – all act synergistically, and that this also applies to related problems on Earth. I felt a strong need to study this comprehensively, and decided to establish this project.

Creating something new through comprehensive study

— What’s the research framework for this project?

Closed environmental adaptation training module

Closed environmental adaptation training module

The aim of this project is to carry out comprehensive cross-disciplinary research, and create something new. Currently, there are 11 research teams, including JAXA, each responsible for its own field of expertise. For example, we are studying stress using JAXA’s training equipment for adapting to a closed environment. In this project, experts in psychophysiology, sleep, cerebral blood flow, and microbiology are working together, integrating their expertise.

For a study of muscle atrophy in space, experts in various fields are working together to consider it not only from the perspective of muscle, but also from that of blood vessels and nerves. That allows us to integrate different perspectives and broaden our outlook. We’ve already been able to achieve positive results by exchanging information and opinions, and we feel we can continue to make progress by maintaining good communication.

— Are you personally participating in the research?

My team and I are studying the psychological implications of a closed environment. When people from different cultures, speaking different languages, live together in a closed environment, stress can build up and relationships can become strained. I have heard about good friends whose relationship soured while they were locked up together for a long time.

Currently on the ISS, experts in psychophysiology regularly interview the astronauts, and if stress levels have increased, adjustments are made, such as a reduced work volume. But if in future astronauts go on longer missions, for example to Mars, there will be a time lag in transmissions, and experts will not be able to talk to the astronauts in real time. Instead, we have to find a way to measure stress objectively.

Consequently, we are searching for a marker that can quantitatively evaluate stress reaction from many angles. There are already some candidates for stress markers such as tone of voice, but we would like to find something new. In space, there is not just a closed environment, but also stress from increased radiation exposure. How to evaluate stress in this complex environment is an issue.

Strengthening the research teams, maximizing achievement

— How did you build your research teams?

Living in Space Research Project Logo

Living in Space Research Project Logo

At first, I reached out to scientists I knew, who had experience in space experiments, their acquaintances, and acquaintances of their acquaintances. From these people, I formed 11 research teams. In order to apply for funding, we had to have these teams committed to certain research projects. But we are currently recruiting more researchers through an open call. The application deadline has already passed, and we are selecting candidates based on criteria set out by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. We expect our teams to get stronger as we add new studies, allowing us to maximize the achievements of the entire project.

— Can you tell us about the five-year goals for this study?

There are three goals. The first is to determine the dependence that living organisms on Earth have on gravity, and their plasticity and collapse mechanisms at the cellular and genetic level. Plasticity is the adaptation and repair functions of living organisms in response to external change. When a person is in a zero-gravity environment, muscles atrophy, and the ear vestibule, which controls our sense of balance, is affected. After some time, our bodies adapt to the new environment – that’s called plasticity. But if we exceed a certain limit, our body starts to break down, and is unable to return to its original condition. We plan to study this collapse mechanism also.

Second, we would like to understand how stress from zero-gravity, a closed environment and irregular sleep affects living organisms. We will study how stress changes the human autonomic nervous system and sleep function.

Third, we hope to identify the environmental risks of living in space. In particular, we would like to look at the effect of radiation exposure on the body, and how microorganisms adapt to a closed environment. In addition, we hope to discover new functions of the human organism that have not been identified in studies performed on Earth. Gravity is not something we normally think about, but we should recognize the significant influence it has on our body.

Benefits in space and on Earth

— How will the results of this research benefit our life?

I think the results of this research will enrich our lives. If we can identify the mechanism that causes bones to weaken and muscles to atrophy, this will benefit preventative medicine for the elderly and help create a healthy aging society. If the effects of stress on the body can be understood, this will provide insights that could lead to a stress-free society. The study of radiation will also reduce risks faced by people who cannot avoid being exposed to radiation at work. The achievements of this research may not directly lead to the creation of new products now, but they may contribute to major discoveries in the future.

— Are you keeping future space exploration in mind as well?

Yes, I hope this will be of benefit for even longer stays in space as human journey to the moon and Mars, as well as future human life in space. However, the purpose of this project is not just to contribute to future space exploration, but to gain a better overall understanding of living creatures, from microorganisms to humans, through research on life in space. We feel that by studying human life in space, we can learn more about how the human body regulates its functions on Earth. And in addition, the knowledge we gain will be beneficial to humans living in space.

— Please tell us about your future plans.

This is a very precious opportunity to study the effects of space on living organisms, so I would like to organize this project so that we can maximize our results, benefiting human life both in space and on Earth. I am participating in this project in order to share what I personally experienced in space, and to explain why this kind of research is needed. For example, gravity sickness after returning from a long-term stay in space didn’t used to be seen as a problem. But given my own terrible experience with gravity sickness, I can say that it could definitely become a major issue on manned expeditions to Mars, etc. From now on, I will continue to try to use my experience to advance further research. As an astronaut, I would like to fully support my junior fellows. And, if given the opportunity, I would like to return to the ISS, and experience life in space again.

Related link: Living in Space

Satoshi Furukawa M.D., Ph.D.

JAXA Astronaut

Head of the JAXA Space Biomedical Research Group, Flight Crew Operations and Technology Unit,

Human Spaceflight Mission Directorate, JAXA

Representative of the Living in Space Research Project

Dr. Furukawa graduated from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Tokyo in 1989, and received a Ph.D. in Medical Science at the same university in 2000. From 1989 to 1999, he worked in the Department of Surgery at the University of Tokyo, the Department of Anesthesiology at JR Tokyo General Hospital, the Department of Surgery at Ibaraki Prefectural Central Hospital, and at Sakuragaoka Hospital. In 1999, NASDA (now part of JAXA) selected Dr. Furukawa as an astronaut for the ISS, and he began basic training, receiving his certification in 2001. In addition, he has participated in the development and operation of JEM Kibo. He was certified as a flight engineer for the Soyuz-TMA spacecraft in 2004, and as a Mission Specialist by NASA in 2006. He was a Flight Engineer on the ISS in 2011 (Expedition 28/29). His mission included experiments in Kibo, and maintenance of the space station. In 2014, he became Head of JAXA Space Biomedical Research Group.

[ April 13, 2016 ]

- Team Japan Earns the Trust of the World

- Rock-Solid Technology, Made in Japan

- New Directions for Research on Kibo

- In Space There Is So Much to Learn

- Studying the Human Body in Space Can Shed Light on Life on Earth