The Beginning of Japan's Space Exploration

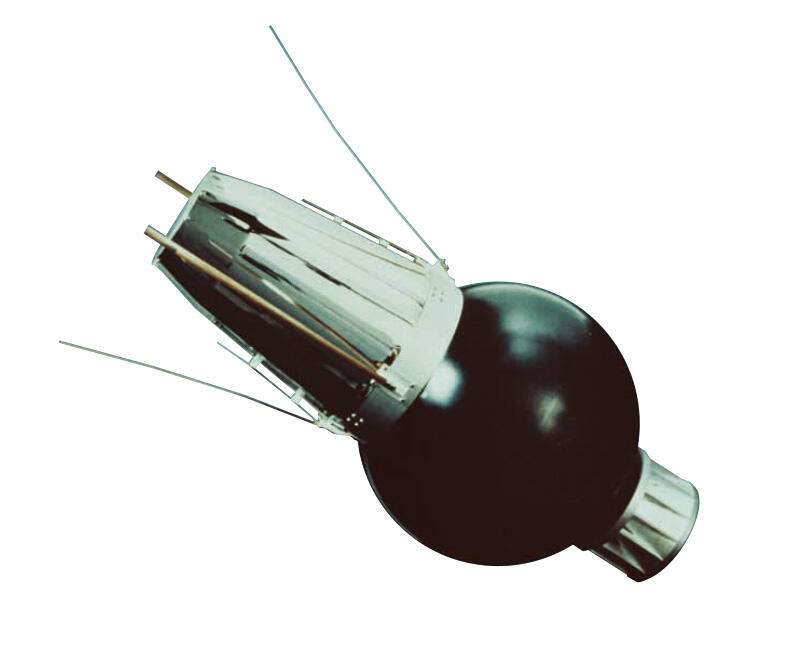

50 Years since OHSUMI, the First Satellite Orbited by Japan

It has been 50 years since the launch of the first satellite orbited by Japan, OHSUMI, in 1970. On this occasion, we're taking a look back at the achievement of launching OHSUMI with INOUE Kozaburo, who was involved as an engineer at the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, University of Tokyo (forerunner to Institute of Space and Astronautical Science of JAXA).

The Quest to Create Japan's First Satellite

Japan's space exploration began in 1955. The country's attempts to reach space accelerated after Professor ITOKAWA Hideo, "the father of Japanese rocketry," led his study team from the Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo, in conducting Pencil rocket experiments.

In 1958, Japan attempted observations of the atmosphere with a Kappa rocket, which had evolved from the Pencil rocket, and succeeded in observations of the upper atmosphere at a height of 50 km. After that, the development of large rockets capable of reaching greater heights made progress. In 1962, Japan set the goal of launching a 30 kg satellite within five years, and began work on creating a detailed satellite launch plan.

However, Japan had been pursuing higher launches of sounding rockets up to that point. Developing a rocket equipped with a satellite and launching it into orbit presented a high hurdle to clear. As part of the terms of the country's surrender after World War 2, Japan was not allowed to have rocket control technology that could be repurposed for military use, and also had less funds to sink into development than larger countries such as Russia or the United States. Despite the conditions being less than favorable, it was the strong will and determination of Japan's scientists that kept up the pace of the development.

In 1962, the launch site was moved to Ohsumi Peninsula, Kagoshima Prefecture, for experiments with the Lambda rocket, which has an increased capability to be equipped with a satellite. Then in 1964, the University of Tokyo's Aeronautical Research Institute and part of its Institute of Industrial Science merged to establish the Institute of Space and Aeronautical Science, University of Tokyo. Rocket performance grew year by year amidst the height of the country's rapid economic growth. Looking back at that time, Mr. INOUE comments, "It really was a time just overflowing with energy. We were conducting rocket experiments with great excitement, sometimes making new discoveries, sometimes failing, and always sharing our joy when we succeeded at observations."

Really Circling the World

The first launch of the L(Lambda)-4S Rocket in September of 1966 was a failure. Following that, the Lambda plan would go on to fail four consecutive times. The media reported widely on the repeated failures, and the public strongly criticized the program.

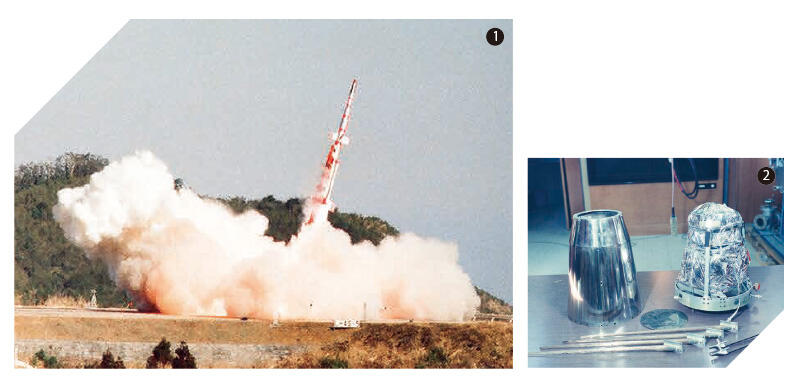

In the midst of such adversity, the launch team made their fifth attempt. At 1:25 p.m. on February 11, 1970, L-4S Rocket No. 5 was launched. The rocket flew successfully, and launched the satellite safely into orbit, finally giving birth to Japan's first satellite. The satellite was named OHSUMI because of its connection to the launch site on the Ohsumi Peninsula.

② OHSUMI's instrument section and antenna

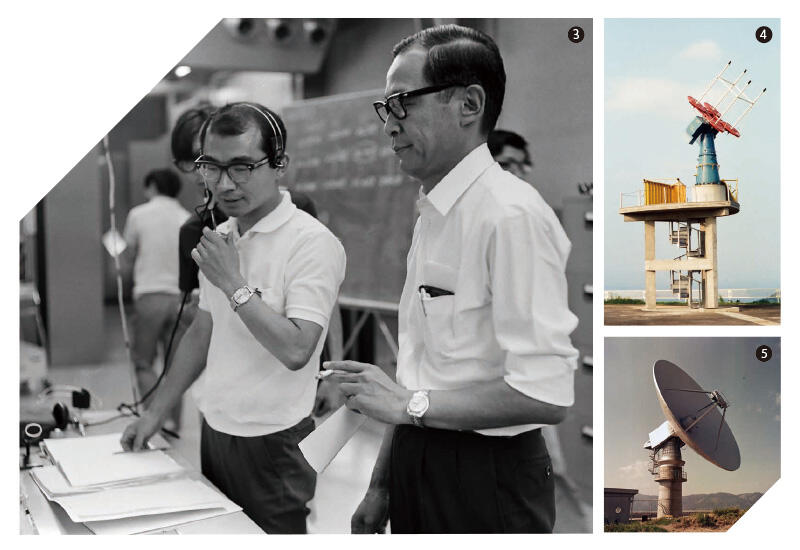

After the rocket left sight, the tension remained at the launch site. The experiment could not be deemed a success until it was confirmed that OHSUMI had circled Earth once and returned over Japanese skies. The telemeter team, of which Mr. INOUE was a member, was receiving the information transmitted from the rocket and satellite for that purpose. Mr. INOUE was in charge of monitoring the received signals and reporting hourly on the flight status of the rocket by dispatch phone. It was an important role that carried the responsibility of confirming the success or failure of the project.

Each successive tracking station of NASA, which was cooperating with tracking the satellite, reported on receiving the signal after launch─Guam, Hawaii, Quito (Ecuador), Santiago (Chile), Johannesburg (South Africa). Finally, at the Uchinoura Space Center in Japan, at 3:56:10 p.m. approximately two and a half hours after the launch, OHSUMI's signal was successfully received.

"The signal beam from OHSUMI arrived two and a half minutes later than predicted, coming from the direction of the western mountains. When the tracking antenna first received the radio wave, the 18 meter antenna was also immediately able to pick up the signal. The signal lasted approximately 10 minutes, but the equipment loaded onto the satellite was working properly. At that moment, I realized that the satellite had really circled the world," says Mr. INOUE.

"All the members of the experiment team felt instantly relieved, and leapt from the lowest depths of worry to the highest heights of joy. As for myself, I felt a wave of happiness gradually come over me. Professor NOMURA had been extremely restless since the launch, waiting for this moment in a corner of the telemeter center. I can still remember shaking hands with him and congratulating each other."

The Professor NOMURA that he refers to is NOMURA Tamiya, who was the head of experiments for L-4S-5. He supported the electricity department during the time when Japan's rockets were growing in size from the Pencil rocket to the L-4S rocket, and would go on to be instrumental figure in the establishment of the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science.

④ The 136 MHz tracking antenna that first received a signal from OHSUMI

⑤ This 18-meter diameter parabolic antenna improved the telemeter receiving capability in preparation for the extension of the rocket's flight distance.

A Mission that Is Also a Dream

The OHSUMI signal was interrupted 14 to 15 hours after launch. However, OHSUMI would continue circling Earth for the next 33 years. On August 2, 2003, it broke up in the atmosphere over North Africa. By coincidence, 2003 would be the year in which Mr. INOUE would reach retirement age.

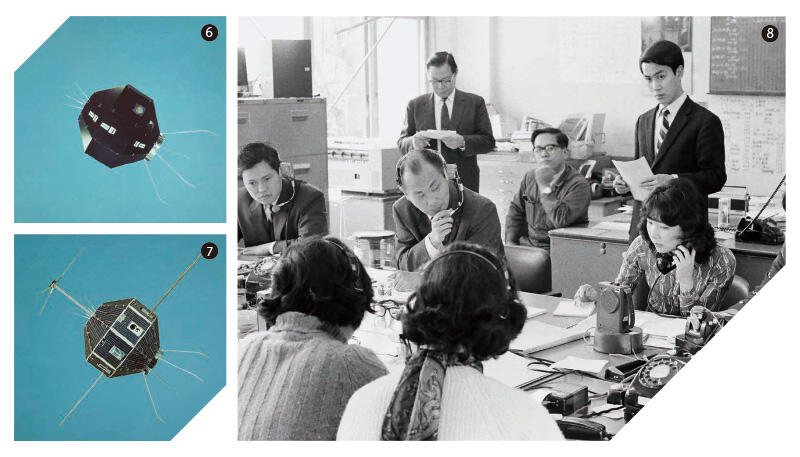

The success with OHSUMI has become a guide for pioneering Japan's space exploration. The satellite technology developed through using L-4S rockets included the "gravity turn maneuver," which uses the gravity of the earth to launch a satellite into orbit by launching it horizontally and controlling the attitude only during the final stage. This method would later give birth to the launch of a full-scale scientific satellite with a Mu rocket. Also, the many failed experiments provided a wealth of data used for assessing possible risks, and this is considered one of the main factors that made possible the subsequent rapid growth of ensuing developments. From the HAKUCHO, which long ago contributed to studying X-ray-emitting celestial bodies including black holes, to the Hayabusa, which succeeded in returning to Earth with the world's first asteroid sample--Japan has launched many space probes and scientific satellites since OHSUMI, and has continued producing numerous valuable results.

⑦ Japan's first scientific satellite, SHINSEI, was also launched in 1971.

⑧ At the Uchinoura Space Center during a satellite launch

Now a veteran at 81 years of age, Mr. INOUE speaks of his hopes for the next generation of space exploration: "I want engineers and researchers to think with freedom, and conduct a mission that is also their dream." The "mission that is also a dream" which Mr. INOUE speaks of refers to a project like OHSUMI; one in which scientists take on a challenge amidst adversity and find worth in their work. And Mr. INOUE says that to take hold of that dream, it's more important than anything to have the desire to "understand the mysteries of space" in one's heart.

A video that commemorates the 50-year launch of OHSUMI can be accessed here:

https://youtu.be/CdG8c4M-XIg(Full Length Feature)

https://youtu.be/rlUdlK7Zwds (Feature Digest)

Profile

|

|

|---|

All the images are copyrighted ©JAXA unless otherwise noticed.

- Home>

- Global Activity>

- Public Relations>

- JAXA’s>

- JAXA's No.82>

- The Beginning of Japan's Space Exploration