Special Talk: Science and Art, and What Lies on the Border Between the Two

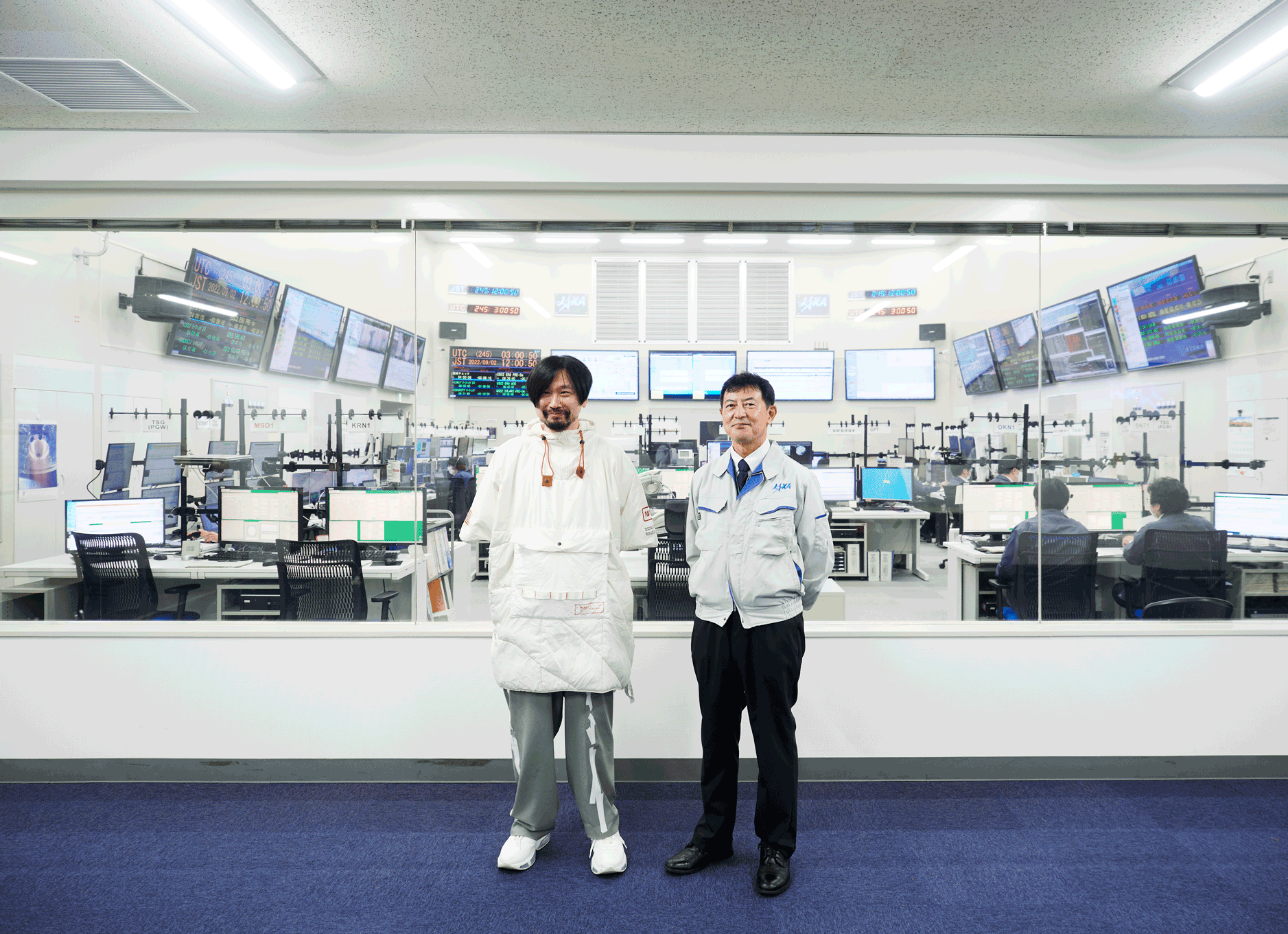

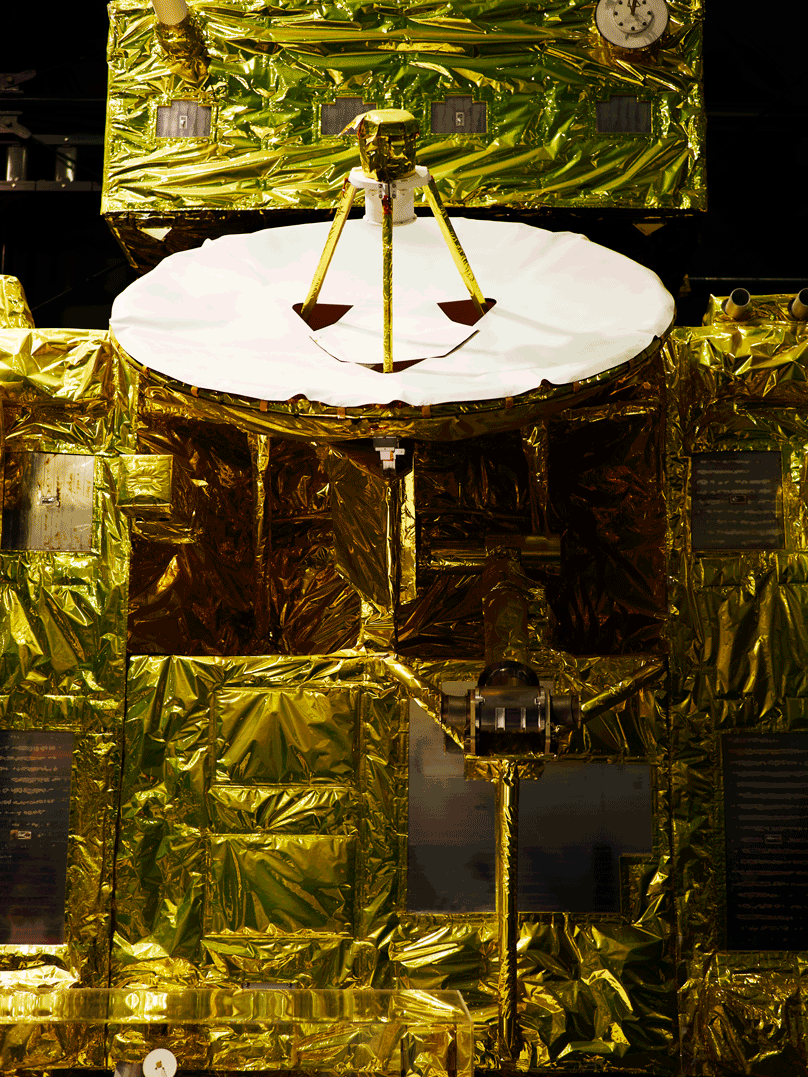

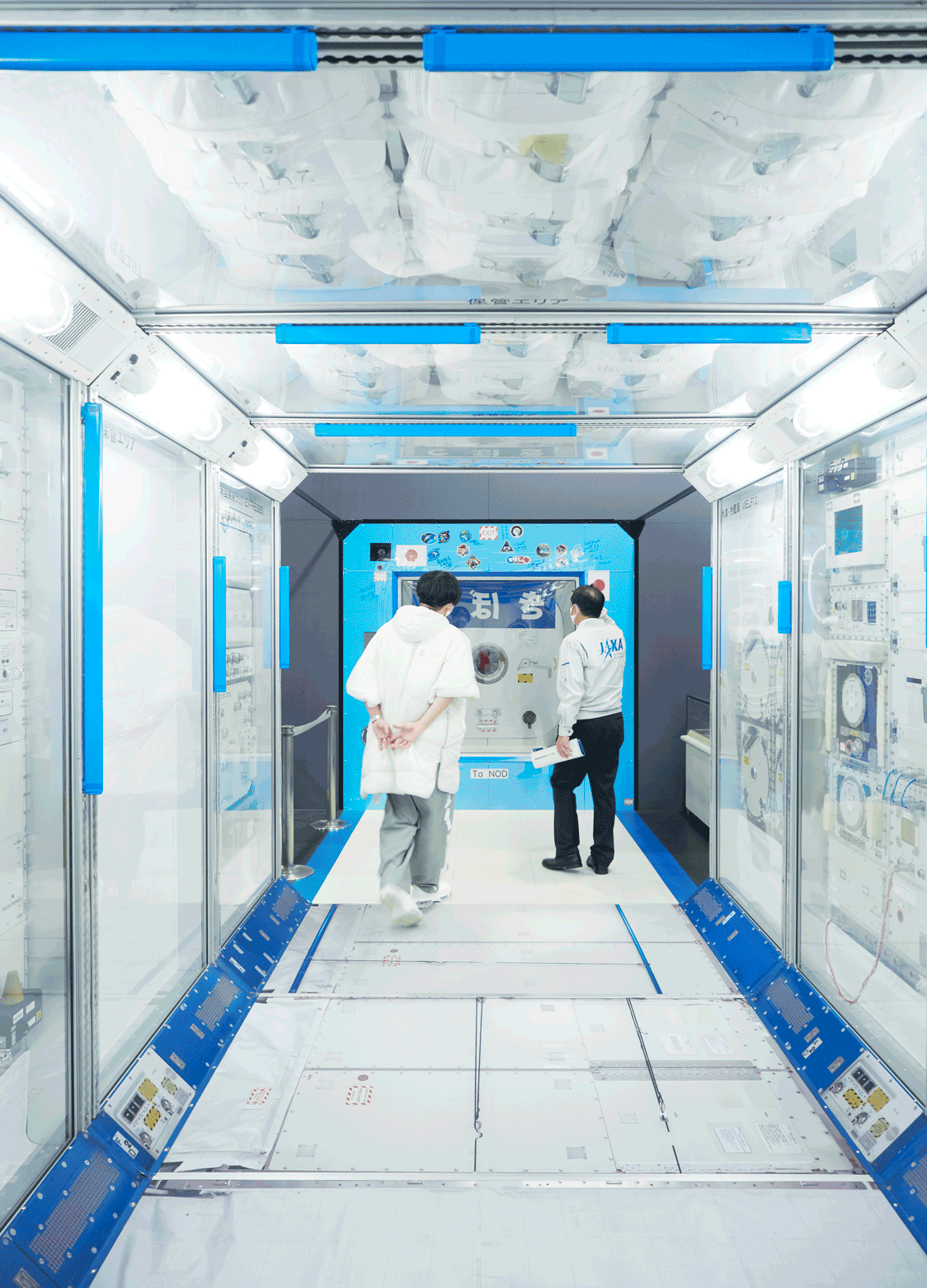

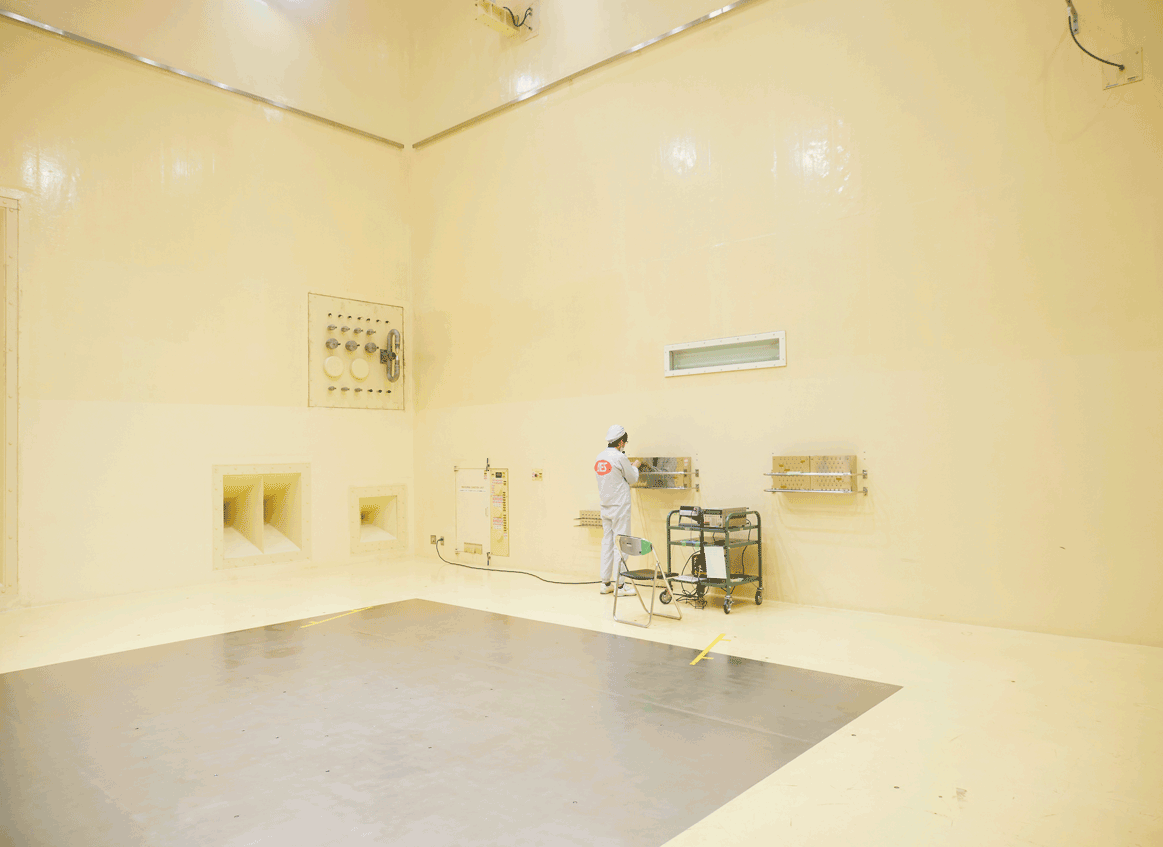

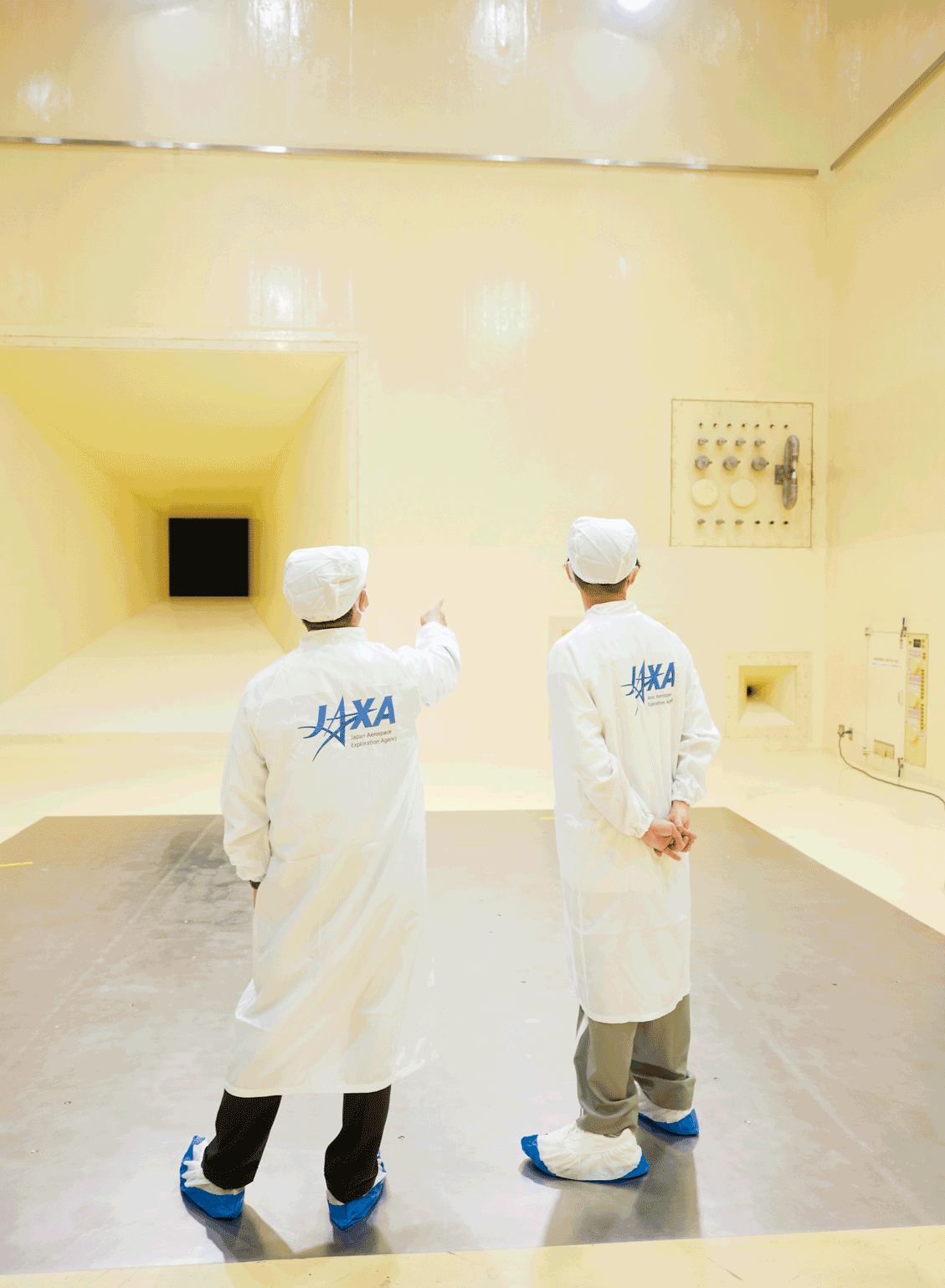

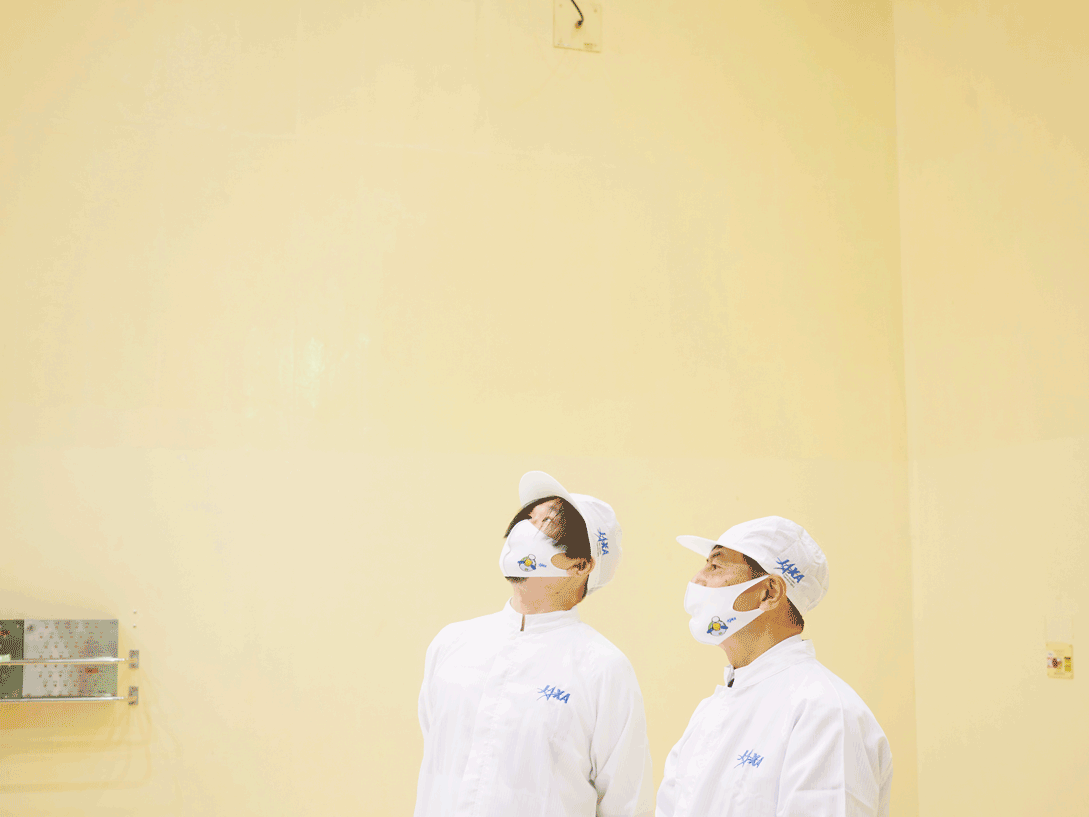

The Tsukuba Space Center was established 50 years ago as a facility for tracking and controlling satellites. The photo was taken at the Space Tracking and Communications Center, which operates the satellites.

Special Talk

Science and Art, and What Lies on the Border Between the Two

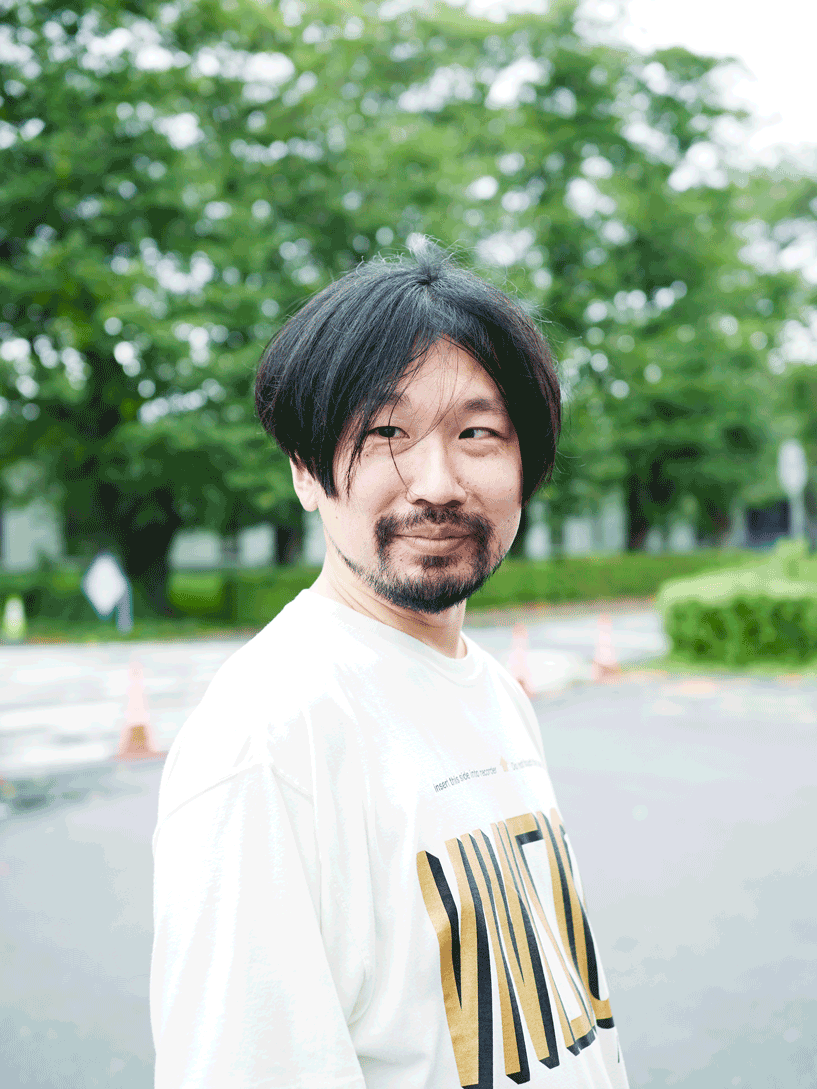

KODAMA YuichiVideo Director

×

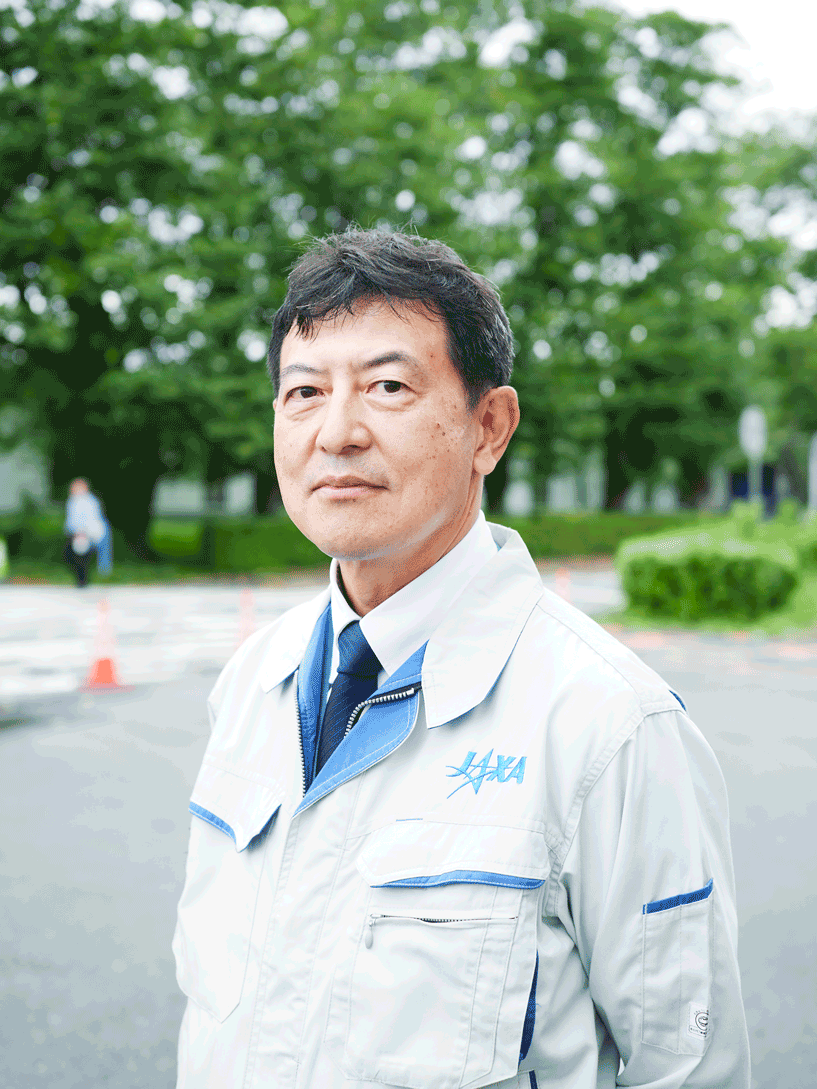

TERADA KojiJAXA Vice President, Tsukuba Space Center Director

KODAMA Yuichi dreamed of being a scientist when he was a child and, though he has now become a video director, he still has a special place in his heart for space and science. Kodama visited the Tsukuba Space Center, celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, and was shown around the facility at the forefront of Japan's space development by JAXA Vice President and Tsukuba Space Center Director TERADA Koji, who has been involved in developing satellite systems for many years and who also heads the division in charge of satellite development and utilization. The two talked about the creativity of science and art as they walked around the Center.

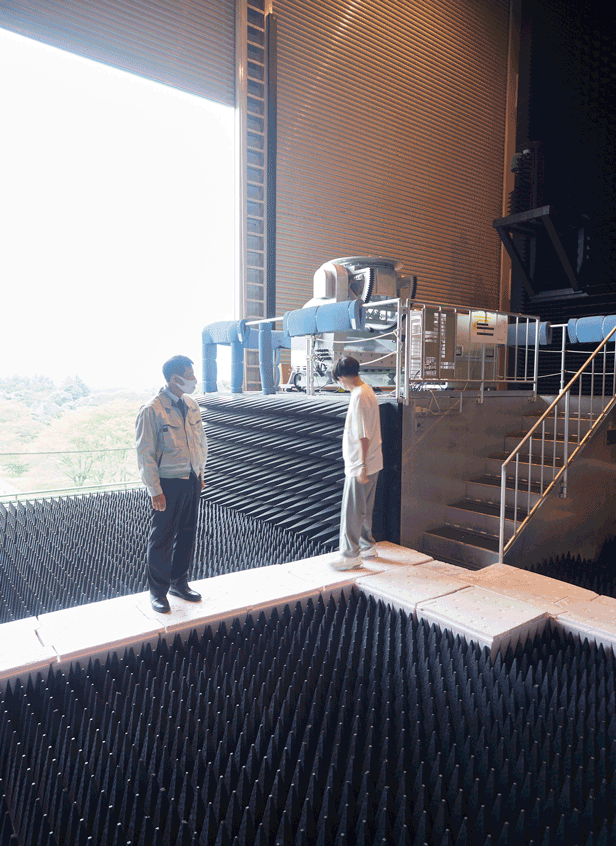

Creating a terrestrial environment harsher than outer space

Terada

Welcome to the Tsukuba Space Center! Thank you for coming today.

Kodama

I was actually very impressed as I walked through the facility. While we were walking around, you spoke about “creating space on earth” and, when I think of the progress made since this facility was constructed in Tsukuba 50 years ago for that purpose, I'm amazed all over again.

Terada

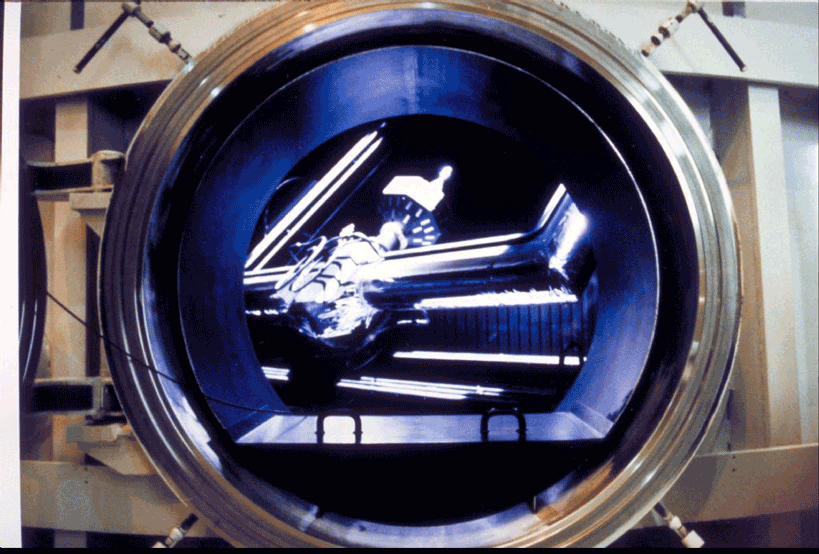

Fifty years ago, the United States had already put men on the moon with the Apollo program but Japan's space development was still toddling along. We decided then to launch a satellite into space, and constructing the facilities necessary for satellite development and operation marked the beginning of the Tsukuba Space Center. Space is a harsh environment for human beings, but the environment getting from Earth to space is even harsher, so a major issue at the time was building satellites and rockets capable of withstanding all conditions they would encounter. In order to simulate that environment, it was necessary to bring space down to Earth.

Kodama

Just imagining the process is daunting but at the same time inspiring.

Terada

There is one aspect of space that we just can't reproduce on Earth, though, and that is a zero-gravity environment. The antenna of a satellite is a deployable structure that is folded like origami in the rocket and then extended widely in space, so a key question is how to test a satellite on the ground that is to be actually deployed in space.

Kodama

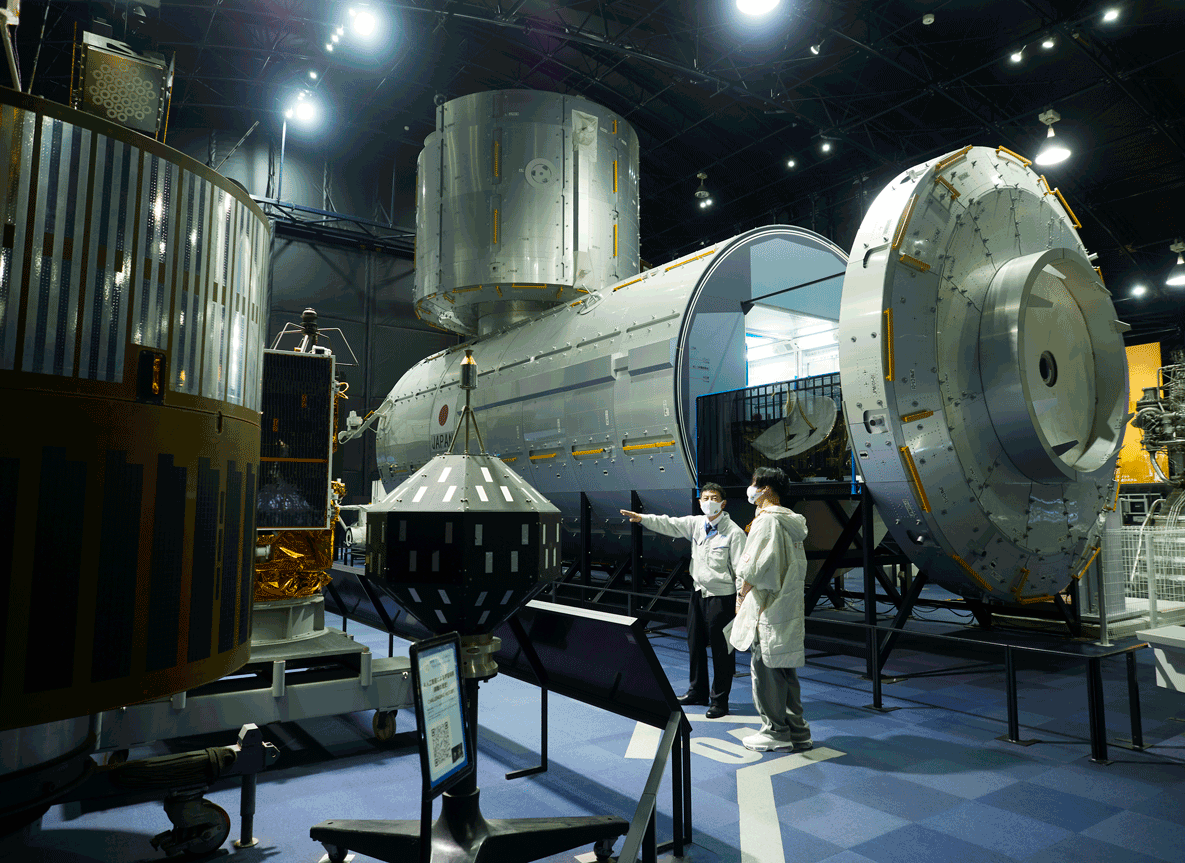

It looks like it would be difficult to do this with satellites such as KIKU-8 (a communications and broadcasting satellite) that I saw at the Space Dome (exhibition hall) because of its large antenna.

Terada

KIKU-8 has an antenna about the size as a tennis court so that mobile terminals can communicate with each other. I was in charge of antenna development at the time. Once in space, the antenna goes from a bud to a large chrysanthemum in about 60 minutes. How could we reproduce that deployment structure on the ground, where there is no escape from gravity? It was a real trial-and-error process.

Kodama

This unfolding structure, which human beings have compacted to the extreme in the interest of utmost efficiency, is maximized the moment it gets into space, a truly beautiful thing. For me, it's an ideal expression of creativity. So how did you finally test in on the ground?

Terada

The answer is that we tested it by suspending the antenna. We tested the gradual unfolding of a folded and suspended antenna having weight. The most important thing to remember here is that, even if the antenna deployed cleanly, gravity might have supported the deployment, so we created an environment on the ground harsher than that in space and tested it there. Another challenge was that deployable antenna parts like those on KIKU-8 are made of soft materials such as cloth, so it was difficult to predict what shape they would ultimately take when placed in a zero-gravity environment. The soft materials caused many problems during the ground tests, with parts getting stuck and the antenna not opening, so we made adjustments each time this happened. In other words, human imagination compensated for the portions of the design that could not be simulated by technology.

Kodama

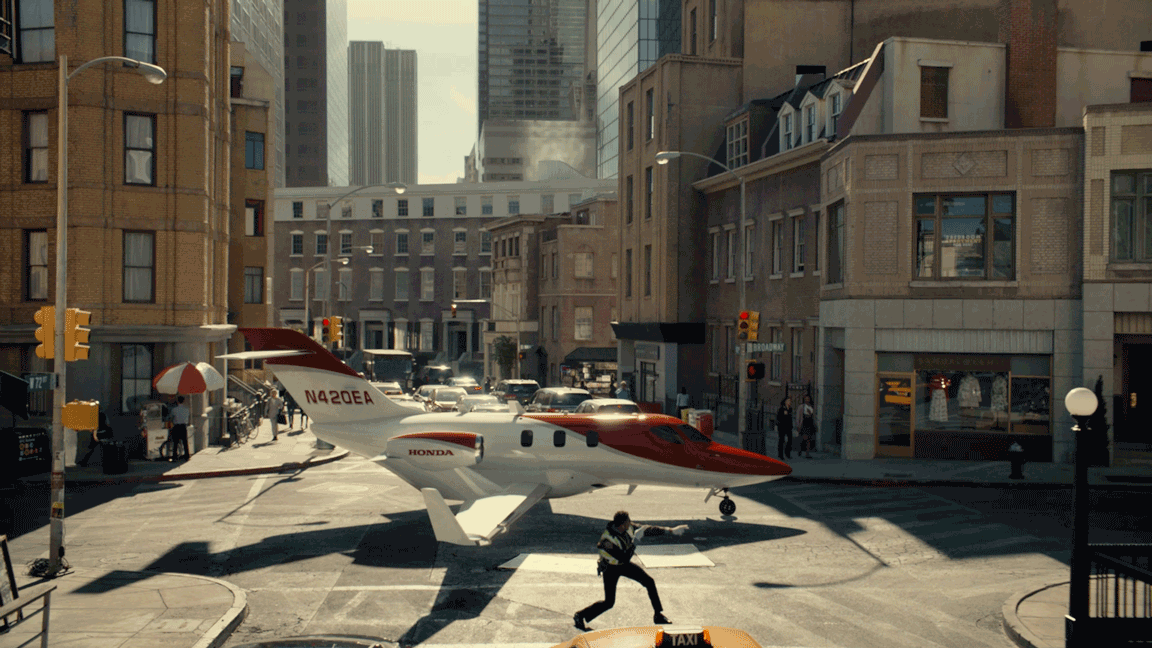

This is indeed where the real thrill of making something lies. I myself often have to create situations that do not exist in reality when shooting commercials or music videos. This is on a completely different level from testing technology for use in space, of course, but when we want to shoot a person floating in space, for example, we have to ask ourselves how to arrange hair to make it seem more realistic, and this triggers some intense back-and-forth debate. It takes quite a lot of effort to create the environment and situation, but I think it is still the best part of the process.

Terada

That's right. If a malfunction were to occur on the ground, we could go repair it immediately, but this is not the case in space. I think the real appeal of space development is always assuming the worst and then verifying equipment in extreme environments. Thus, the various test facilities we showed you today can be said to be locations for creating an environment harsher than that of space.

Design resolves or makes the most of constraints

Kodama

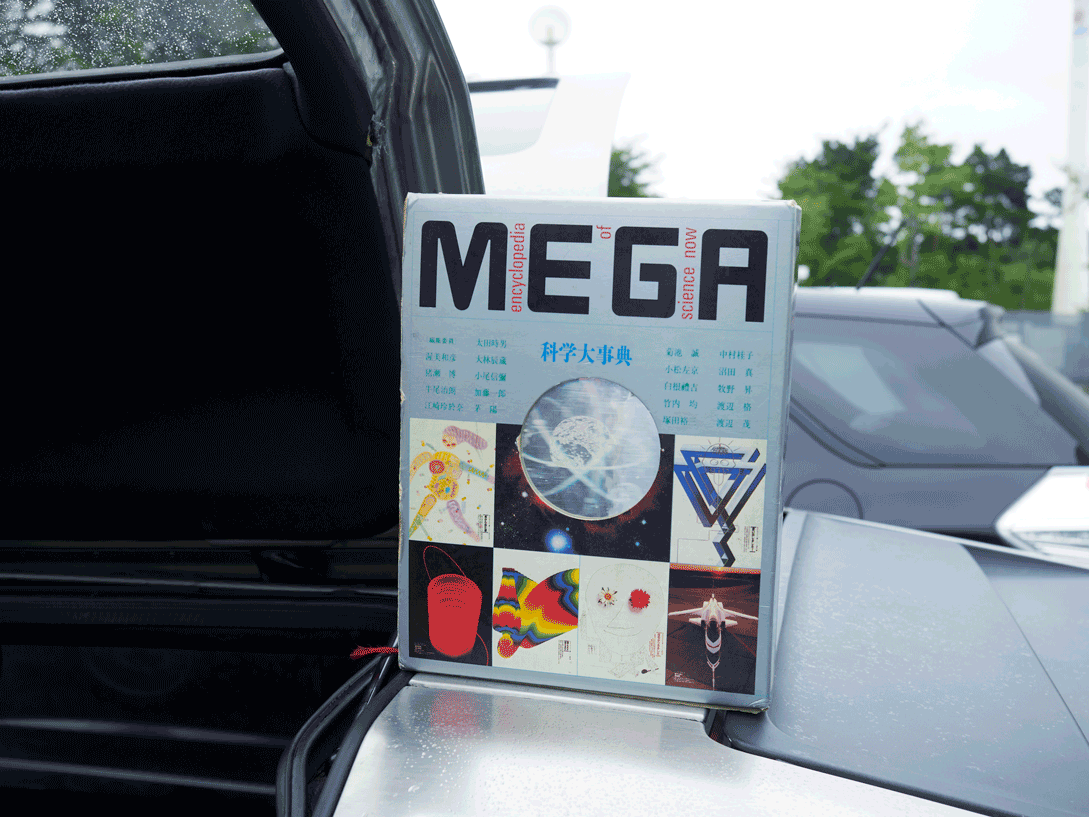

When I was a child, I loved our local science museum (Niigata Science Museum) and often went there, and I naturally thought that I would become a scientist in the future.

Terada

So you were a science kid. What was it about the science museum that stuck with you the most?

Kodama

Everything from the exhibits to the goods sold at the store. Looking back on our local science museum now, I think it was of very high quality in terms of design. I saw the video “Powers of Ten” directed by Charles and Ray Eames there for the first time, and I found something exciting to my child's mind every time I went.

Terada

How did you go from there to your current path?

Kodama

I enrolled in my university's faculty of science with the intention of becoming a scientist, and started on the path of studying chemistry. Then I thought again about what I liked about science, and I realized that I also enjoyed design related to science and technology. Chemical formulas, the periodic table of elements, the NASA logo, the Voyager spacecraft record disc, science museums' signage planning -- they were all cool and beautiful, and it was at that point that I became interested in design and video, which led to my career as a video director. Even now, though, I feel grounded in science. For instance, when I think of a beautiful parabola, the source of my ideas when I'm considering videos is scientific, and my mind always seems connected to science and technology, going back and forth between that and videography.

Terada

I've seen several of your videos, and “UNIQLOCK” stuck strongly in my mind. First of all, the images are beautiful. My specialty is engineering, and I've been developing satellite systems at JAXA for many years. When developing satellites, I'm surprisingly conscious of rhythm and balance, and I felt a similar kind of rhythm and balance in the “UNIQLOCK” video.

Kodama

Oh, really?

Terada

Space is an ultra-high vacuum environment with extreme temperature differences. There is strong radiation from the sun, and there are many other constraints when it comes to flying a satellite in space. For example, the center of gravity must be in the exact center of the satellite to keep it from moving unevenly, and solar panels must be attached. The design must also ensure that the field of view of the sensors used to observe Earth is unobstructed, and so on. The shape of a satellite is the result of eliminating various constraints, but there is a certain beauty in the inevitability of the shape. It can be very simple, regular, symmetrical, and so forth. I felt the same kind of rhythm and balance in the “UNIQLOCK” video. The alternating images of female dancers dancing to the sound of a time tone and then of clocks had a beauty that was structured within the video's constraints.

Kodama

I'm so happy to hear that. I myself believe that design and creativity are about resolving or making the most of constraints. “UNIQLOCK” was a video and music piece, a website and a blog widget with a clock function, but it was shot in 2006, when the Internet environment was still in its infancy. Nevertheless, we wanted to compete with high-quality images and, since it was a clock, we wanted to be able to stream it 24 hours a day, seven days a week. After thinking about what to do, we chose to alternate between a five-second programmatically-rendered clock and a five-second dance segment. It is very data-intensive to play the full HD video all the time, but the dance segment is actually being downloaded while the clock is being displayed. Doing this allows us to create content that delivers beautiful images forever without interruption. Order emerges from all of the elements ticking away the seconds, and this was exactly the beauty created through structuring.

Tenacity and commitment are the beginnings of exploration

Terada

I was surprised that “UNIQLOCK” was a video shot in 2006, because it had a newness to it that made it hard to believe that it was shot more than 15 years ago. I was wondering how you always come up with your ideas.

Kodama

Ideas sometimes emerge unintentionally, by chance or through playing around, and I find that interesting. When this happens, I don't immediately use them for anything but instead I leave them on my desktop until the day comes that I can make use of them. I'm also the type of person who saves my mistaken or failed footage, because I can sometimes mix up compounds never seen before from these failures. That's why I'm hesitant to throw anything away. As a consequence of this mindset, my computer desktop is surprisingly messy. The entire screen is covered with files, and people seeing it always say, “What the heck!” (laughs).

Terada

Don't you lose track of where things are?

Kodama

I myself don't even know where anything is (laughs). When I click on an unfamiliar folder, though, an image that I hadn't expected at all comes up. It works for me as something resembling random access memory.

Terada

I see. That's interesting, because making use of coincidence is not easy to do in space development. There's one more thing I wanted to ask you. A moment ago you mentioned saving your mistakes and failures; how do you go about recovering from those? Space development involves repeated trial-and-error, and what I have paid most attention to in developing satellites are the lessons learned from this process. I regard all my failures and regrets as feedback and try to make use of them to prevent recurrences the next time I develop a satellite. Do you usually follow a pattern of utilizing such failures when pursuing subsequent projects?

Kodama

Yes, I never forget the frustration of failure or, rather, I always carry it with me. At the same time, there is necessarily a deadline to meet - I'm sure the same is true in space development - so I can't just stop after a failure. They key is how quickly I can move on to the next stage. That said, I'm carrying that frustration with me all the while I'm making this changeover (laughs).

Terada

Deadlines are important. How you make the most of what you are carrying with you the next time around is key. I feel that a creator's talent is also manifested in his attitude and demeanor.

Kodama

It may be that I'm persistent. I don't remain content for very long after completing a video. Since video technology is evolving at a dizzying pace, we are able to achieve more and more that we couldn't do before, so we are always trying to make a comeback.

Terada

Tenacity and commitment. That is exactly what exploration calls for. I think space development is similar. As you saw in the test facility today, there is no way the initial test will be completed perfectly without any defects, so we have to struggle with all kinds of problems until we succeed. These cannot be overcome without commitment, and there is also the struggle with deadlines.

Kodama

I have a genuine sense of that now, and once again I realize that space development is an endless world.

Ensuring the Tsukuba Space Center supports dreams

and helps realize them

Terada

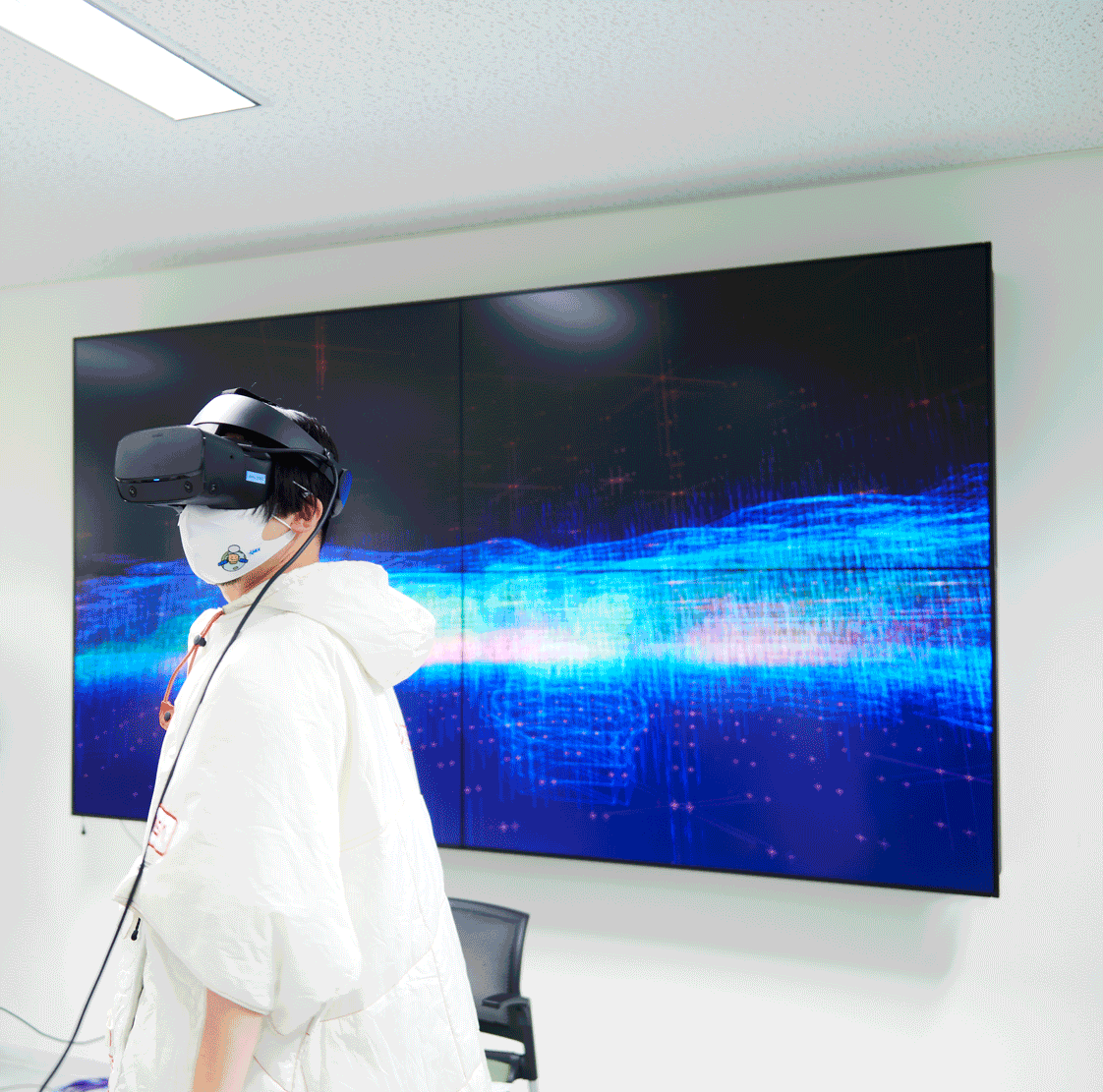

I think the process of editing images after they are taken is another creative endeavor. For example, our real work only begins after we develop a satellite, launch it, and obtain Earth observation data from space, and we are constantly researching ways of making that data easier to use on the ground. The observation data you saw today at the Earth Observation Research Center (EORC), for example, was not just visually-rendered sensor data from JAXA satellites but was instead a product of human imagination created from a compilation of multiple sensor data sets supplemented spatially and temporally to make the data easy to use while achieving as much accuracy as possible in the face of various constraints. The same is true for the visualization of raindrops in a three-dimensional structure. We are always looking for ways to inspire scientists and researchers, and to make users feel comfortable utilizing the data.

Kodama

You've just talked about people feeling comfortable utilizing data, and I think a clue for getting to that point can be found in the sense of incongruity or discovery prompted by a void. In fields such as weather forecasting, where speed has a higher priority than perfect accuracy, bold innovations have been made that go beyond calculations and logic to physical senses and needs, leading eventually to technologies and data widely used by the general public. These voids are filled in with predictions and ideas, and then turned into domains that can be used by humans. I was able to pick up on these aspects of science and technology as you showed me around, and I was reminded of how wonderful science and technology are.

Terada

Indeed, a sense that something feels off is very important.

Kodama

I believe in the video world it is precisely those places that have never been paid any heed that challenge us as videographers. If we can create a new sense of value there, the video will provide the viewer his own discoveries and experiences. This is why I always want to be the first one to discover incongruities. I studied catalytic reactions when I was a university student, and I found that it is often on the boundaries of different environments that the most unusual chemical reactions occur, and I found the gaps and boundaries very interesting. When I wander around such boundaries on a regular basis, I discover new feelings of incongruity and I think this leads to the videos I create.

Terada

I really enjoyed showing you around the Tsukuba Space Center. I could tell that you truly like science and space, and I was glad that your science background helped you understand our perspective. With the Tsukuba Space Center celebrating its 50th anniversary, it would be great if you could shoot some videos that look ahead to the future from the vantage point of different fields of science and technology intersecting to create a new chemical reaction.

Kodama

I can't wait already to get started shooting and recording.

Terada

JAXA's corporate slogan is "Explore to Realize" and I believe that realizing is paramount. We all have our own dreams, ideas and plans, and the Tsukuba Space Center was designed to realize these. Whether you want to resolve social issues, protect the global environment or advance into space, the bigger the dream, the more we want to help, support and realize it over the next 50 years.

Kodama

I'd like to stand at the cusp of people's interest in space and shoot videos that will amplify that interest and make them proud. I'm confident that the person I am today can express the feelings I once had as a child visiting the science museum, so please allow me to lend a hand (laughs).

Terada

By all means, let's make it happen somewhere.

Profile

KODAMA Yuichi

Video Director

Born in Niigata City, he has been engaged in a wide range of activities from planning/directing video productions such as commercials and music videos to directing live performances. He has won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Lions International Advertising Festival, the Clio Awards, and the One Show among a host of other awards. His hobby is collecting space-related items.

TERADA Koji

Vice President

Center Director, Tsukuba Space Center

Born in Niigata (Mr. Kodama was his junior in high school), he helped develop the KIKU-6 and KIKU-8 engineering test satellites and served as Project Manager for the first quasi-zenith satellite MICHIBIKI, Director of the Public Affairs Department, Director of the Strategic Planning and Management Department and Director of the Procurement Department before assuming his current position in April 2020. He is always mindful of balance, rhythm, and change.

All the images are copyrighted ©JAXA unless otherwise noticed.

- Home>

- Global Activity>

- Public Relations>

- JAXA’s>

- JAXA's No.89>

- Special Talk: Science and Art, and What Lies on the Border Between the Two