Special Feature: Tsukuba Space Center Marking Its 50th Anniversary

Tsukuba Space Center Marking Its 50th Anniversary

Former Employee Looking Back into the Center's History

This year (2022) marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Tsukuba Space Center. Located within Tsukuba Science City, the research and education institution has steadily developed over these yeas into what it is today. This article presents the history of the Center prepared based on the interview with SUZUKI Seiji, who served the institution for nearly a half century since its opening, and is known as a "walking dictionary" about the facility.

The Tsukuba Science City project was approved at a cabinet meeting in 1963. The project location was selected in recognition of good accessibility from Tokyo, abundant water resources supplied from Lake Kasumigaura, flat terrain, among other factors.

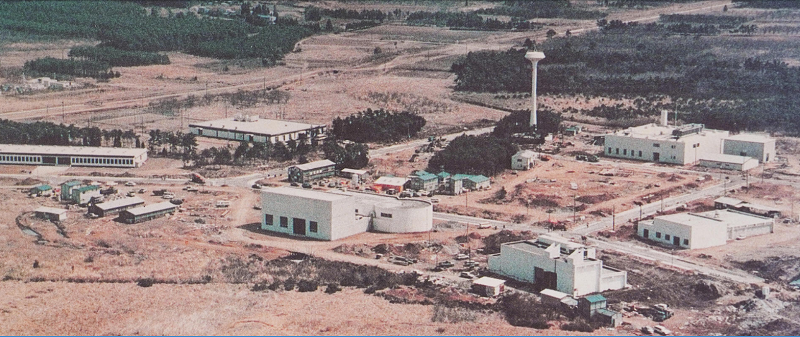

The site of the science city was formerly a large open land dotted with rice and crop fields amid extensive wooded areas, as described by SUZUKI, who was born and brought up in Tsukuba and worked for the Center for decades since its founding.

In 1971, the preparation office for testing and tracking facility was built within the Tsukuba Science City, and the organization was renamed the Tsukuba Space Center in 1972, starting as a center for test facilities on launch vehicles and satellites as well as for tracking and controlling satellites. SUZUKI was employed by the new institution in September the same year, and began to work as a commuter bus driver. The facility stood on the still nearly vacant premises, which was surrounded by crop fields in those days.

Looking back on those days, SUZUKI said, "the Center was located a long way from the town, making it a 'solitary island on land.' I was assigned to serve as a commuter bus driver, because I had a necessary license, and transported employees between the Center and Tsuchiura Station every day. After a while, employee dorms were built, and I began to run bus service for dorm residents to go on semi-daily (morning and afternoon) food shopping trips. In those days, the Space Center in general was not something familiar to local people, including me. So, the Center made efforts to be accepted as a member of the community. I helped with such efforts as I knew many people in the region, including village mayor. I accompanied the Director of the Center when visiting local organizations and hosting opinion exchange meetings with local residents."

Sakura Village, the former name of the district hosting the Center, became a central district of the Tsukuba Science City. Then, as many people were moving in, the village population gradually grew, and reached 50.000 people in 1987 immediately before the village was merged into Tsukuba City, recording the country's largest village-level population in the year.

Planting cherry trees, creating ponds, and running local clean-up events

In its earliest years, the Tsukuba Space Center allowed local people to live on part of its premises since the boundaries of the site were not clearly defined, a practice suggestive of less-regulated, good old days. Afterwards, as the Center's construction progressed, those residents moved out of the site, and resulting vacated spots were used to create stormwater reservoirs for flood control. SUZUKI, a member of the Administration Department at that time, was involved in the related tasks, though they were primarily assigned to the Ground Facilities Department.

Right: Front view of the former Administration Building completed

It was around the time when completed facilities were covering the site and SUZUKI was appointed to be responsible for the environmental improvement of the overall premises. In that capacity, he launched the project of planting cherry trees around the reservoirs.

He described the project as follows, "About 40 years ago, it was suggested that we should plant cherry trees as a way to show respect for the host district, Sakura Village (literally "Cherry Village"). The plan was to buy a total of 1,000 cherry seedlings, which measured slightly more than one meter in length, and plant each of them by hand within the site. Years later when the plants had grown to bear flowers, we began to run seasonal cherry blossom viewing events, opening the specified area to the public. We created and hang special lanterns bearing the name of astronauts and others, including MORI Mamoru, MUKAI Chiaki and DOI Takao. We set up the reception desk to welcome local visitors, and those from inside and outside enjoyed the festive event together. Truly, many people looked forward to this annual occasion."

The above event apparently represented the Center's efforts to promote the concept of "open science city" at that time. Also, it may well be related to its acknowledgement of the importance of having opportunities to exchange with the local community for the purpose of smooth operation of the facility. Today, however, it would be difficult to hold a similar event, given that the recent security control is far stricter than in those days.

SUZUKI moved the above project forward to the next stage, keeping carp in the reservoirs and raising ducks using leftover foods as feed. Then, mallards flew to the spot and coupled with the ducks to have baby birds, which started inhabiting the ponds. These activities aimed to improve the circumference environment of the Center. SUZUKI thought this was very important in order to raise the reputation of the Center.

Among other endeavors made with a similar objective was creating artificial hill, tsukiyama-style garden, so that they would provide an attractive view from the International Space Technology Exchange House, in addition to planting cherry trees. The House is used particularly to welcome VIP visitors to the Center. According to SUZUKI, one of the most impressive VIP visits that the Center has ever received was made in 1989 by the then US Vice President Dan Quayle, who arrived with his bodyguards in a troop of helicopters.

At the same time, SUZUKI was strongly aware of the need to give back to the local community. He talked about a couple of recreational activities organized for the Center's personnel to participate in using local resources.

"Previously, when environmental awareness was lower than today and ecology was not a social issue, many popular mountains, including Mt. Tsukuba, were littered with trash left by hikers. Also, around the same time, many organizations began to recognize the importance of maintaining the health of workers, specifically promoting recreational activities. Given this situation, I suggested a recreation plan for the staff to go hiking in Mt. Tsukuba while doing cleanup on the mountain path. I thought such activities were important in those days, when Japan's economy expanded year after year and people were encouraged to work more to achieve more. The Center's staff also worked very hard. Particularly, their workload became heavier shortly after a successful rocket launch from the Tanegashima Space Center. The Tsukuba Space Center's tracking and controlling team was responsible for post-separation tracking to confirm the satellite entering the orbit properly, which engaged the entire team in stressful all-night operations. That was before the cafeteria was built in the Center, so I arranged meals for them instead. Witnessing staff members working extremely hard, I became worried about their health, and suggested plans to help them achieve healthy balance between professional and personal life. For example, I sometimes invited off-duty members to help with local farm work on fine days and had drinking parties after work."

As part of such activities, SUZUKI occasionally went fishing in Lake Kasumigaura with some members. He also invited many―from Japan's elite engineers working for the Tsukuba Space Center―to help with rice harvest on his farm on weekends in order to provide them with an opportunity for a change of scenery. It was a time long before people began to talk about the importance of work-life balance.

Presenting "real things" in order to communicate the appeal of space science

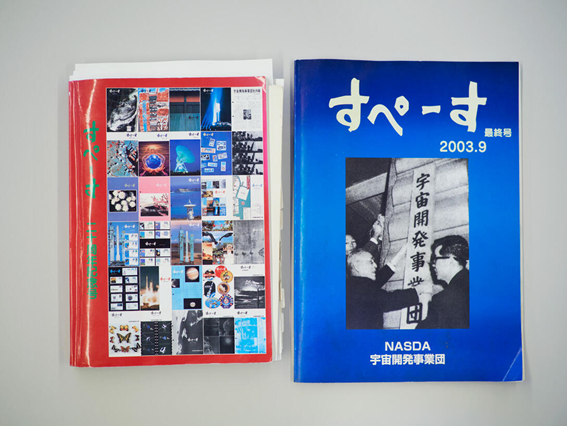

Around 1990, SUZUKI began to engage in public relations. He was assigned to the editorial team of Space, quarterly magazine published by NASDA (National Space Development Agency of Japan), a predecessor of JAXA. In addition, he was tasked with giving a guided facility tour to general visitors to the Tsukuba Space Center. Since the Center was yet to be equipped with an exhibition facility equivalent to the present function, tour programs were organized incorporating real equipment to showcase.

SUZUKI said, "I gave a hands-on showcase of real equipment, often preparing a simulation-like setting to show how the real equipment works, using, for example, centrifugal testing machines and vibration generators used for satellite payloads. We showed a variety of real machines that were available from those housed in the Center. Many visitors enjoyed firsthand experience of engaging with real things. I gave a guide for tens of thousands of visitors in this way. In order to do this, however, I had to study a lot about space science to have adequate understanding, because I was not a professional scientist. I studied really hard. In this light, non-professionals can become a better guide to general visitors."

SUZUKI described the value of showcasing real things rather than displaying replicas. Real space technology can strongly appeal to viewers and inspire their interest in space research and development. Since his first encounter with space science as an employee of the Tsukuba Space Center, he gradually became passionate about learning space science, especially through various thrilling events, such as satellite launches. Then, he became a passionate guide to the Center. He also voluntarily visited to local elementary schools and participated in events to host workshops to craft water rocket launchers, wishing to increase the base of space enthusiasts. SUZUKI himself grew into one in tandem with the development of the Tsukuba Space Center since its founding.

Toward the end of the interview, SUZUKI mentioned his passion about maintaining an attractive and beautiful environment of the site, while walking around on the premises. Looking to the facilities across the reservoirs, he said in a proud tone about receiving encouraging and appreciative words from astronauts. This must be a proof of their firm confidence in his reliable behind-the-scene work supporting the operations of the Tsukuba Space Center.

Profile

|

|

|---|

All the images are copyrighted ©JAXA unless otherwise noticed.

- Home>

- Global Activity>

- Public Relations>

- JAXA’s>

- JAXA's No.89>

- Former Employee Looking Back into the Center's History